The Pleistocene history of Vermont has been the subject of many studies. As noted above, the most comprehensive and now classic work has been by Stewart and MacClintock(S & M) for the Vermont Geological Survey, including an early review of the previous literature 1Stewart, D.P., 1961, The Glacial Geology of Vermont; VT Geol. Survey, Bull. 19, 124 p., a detailed report 2Stewart, D.P. and MacClintock, P., 1969, The Surficial Geology and Pleistocene History of Vermont; VT Geol. Survey Bull. 31, 251 p. .and a map of the entire State.3 Stewart, D.P. and MacClintock, P., 1970, Surficial Geologic Map of Vermont, VT Geol. Survey. . All of these have been referred to in the course of the work done here. The Statewide map, which is depicted in one of the VCGI tabs utilized in the mapping of ice margins, was substantially utilized with regard to the identification of ice margin features.

As noted above and discussed further below, S & M looked at glacial history from the point of view of ice flow directions, leading them to identify three separate and distinct times of advance and retreat. S & M’s thinking about deglacial history entailed a different model, or paradigm, based on stratigraphic differences associated with changes in ice sheet movement directions. When I was a youngster at UVM I had students, not much younger than me, who under my direction examined some of S & M’s evidence, as for example, detailed studies of S & M’s “two till locality” in Shelburne, finding that the evidence for differentiating multiple drifts at this location is not supported.

Now that I have “matured,” especially in light of my Statewide VCGI examination as reported here, my sense now is that back in those earlier times I was too quick to criticize, perhaps as is generally the way in academia. S & M’s mapping was a remarkable achievement for which I now recognize and commend my former friend and colleague Charlie Doll who, as State Geologist, provided the impetus and funding for the S & M study. The S & M map and accompanying report is a valuable data base which contains a large amount of good and useful information, even if I still take issue with some details, and of course have a different modus operandi with regard to deciphering deglacial history. Obviously, the S & M model does not focus on the positions of ice margins during recession. Back in the 1970s, as noted above, I failed to find a solution to the deciphering of deglacial history problem, which now finally is offered vis a vis the “Bath Tub Model.”

The thinking and approach here, in this present report, and therefore as well its findings, as discussed further below, represent a different paradigm. However, it strikes me that S & M’s findings actually may fit and be compatible with the findings presented here. For example, if one considers the flow patterns suggested by ice sheet “Disconnections,” as reported here, compared with S & M’s striations and till fabric, it seems possible that the S & M findings fit with the role and influence of multiple ice lobes in different physiographic settings, and that both their drift sheets and multiple ice flow directions may have merit together with the findings here, giving a more complete history than either alone. Further, S & M were assisted by geologists including Parker Calkin, William Cannon, and G. Gordon Connally. In his open-file report, Cannon clearly recognized that striations indicated that the thinning ice sheet in the Champlain Basin adjusted so as to conform with physiography, which supports the “Bath Tub Model.”

It seems to me that what is needed is a more comprehensive review of the larger regional picture, including Quebec, all of New England, New York, and beyond, taking into account all lines of evidence.

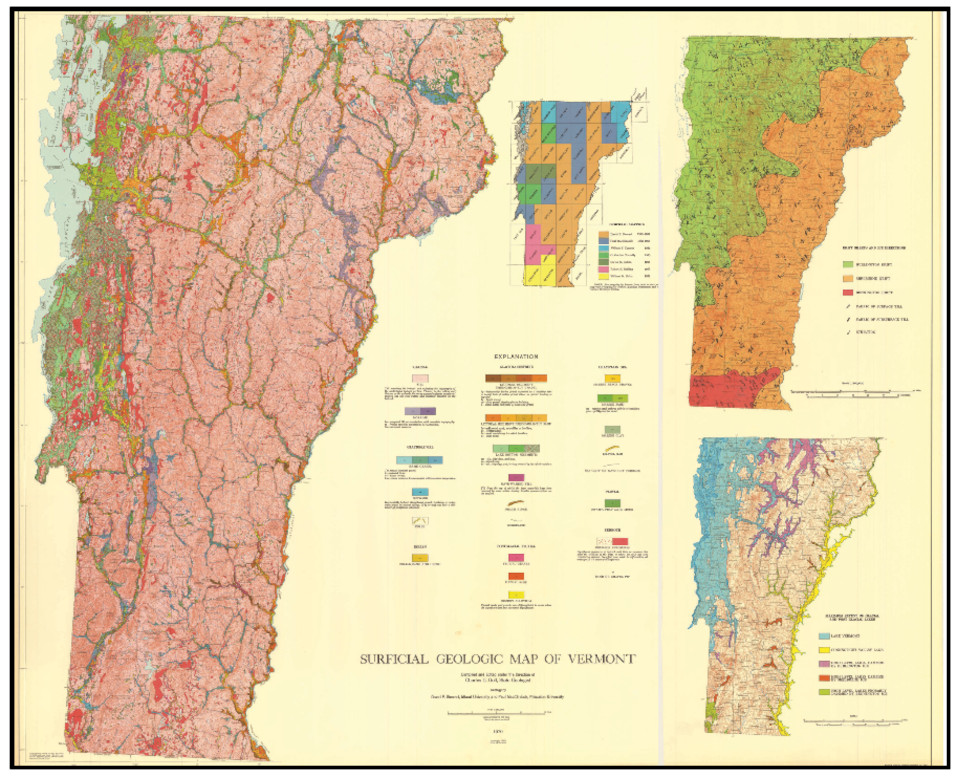

The following is S & M’s map:

Obviously, owing to its scale, this map is largely illegible here and is included for its symbolism. This map served as an exceedingly important and helpful resource for mapping in this present VCGI research, with this map being available in much greater detail as one of the VCGI tabs. The smaller inset map in the upper right depicts S & M’s glacial history map, as described in their 1969 report. As stated by Stewart(1961, p 40) 4 ibid evidence from till fabric and striations led to the concept of multiple ice sheet advances or “invasions,” as represented by three separate drift sheets, including in order from oldest to youngest, the “Bennington,” “Shelburne,” and “Burlington Stades.” Obviously, this is clearly pointing to a glacial history related to flow directions of the ice sheet, which presumably spans a longer time as contrasted with the later deglacial ice margin history being explored here.

The finding by S & M that their drift sheets represent discrete advances has not been evaluated in this present VCGI mapping and cannot be either confirmed or denied. As noted above, studies of the two-till type locality for the Shelburne and Burlington drifts, as reported by Wagner, et al(1972). 5 Wagner, W. P, Morse, J.D, and Howe, C.C., 1972, Till Studies, Shelburne, Vermont; NEIGC 64th Annual Meeting, Trip G-5, pp 377 – 388. failed to confirm significant stratigraphic differences between the Burlington and Shelburne tills. However, so far as known, other locations where S & M report stratigraphic differences have not been fully and independently re-examined.

Stewart(1961) 6ibid discusses the manor of ice retreat in Vermont, for example, the tendency of the retreating ice sheet, owing to the State’s irregular topography, to develop stagnant ice deposits rather than classic end moraines. Quite interestingly, reference is made to a debate regarding the possibility of en masse stagnation of the “Connecticut Glacier” in that basin, an idea introduced in the 1930s. This concept subsequently fell into disfavor, but evidence presented below in this present report suggests en mass stagnation of much of the ice sheet in the Connecticut Basin in Vermont (and perhaps beyond).

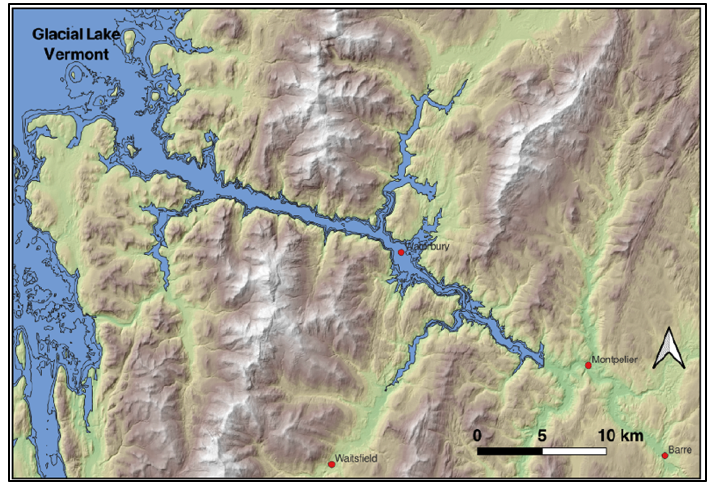

Also, the other inset map in the Stewart and MacClintock State surficial geology map above illustrates the extent of major proglacial water bodies in Vermont, showing the presence of proglacial standing water along the ice margin in the Champlain Basin (proglacialLake Vermont and the Champlain Sea), in the interior of the Winooski and Lamoille Basins (these water bodies have more recently been delineated by Springston et al(2020) 7 Springston, G., Wright, S., and Van Hoesen, J., 2020, Major Glacial Lakes and the Champlain Sea, Vermont: Vermont Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication VGSM2020-1, Scale 1:250,000. , including proglacialLakes Winooski and Mansfield in the uplands of the Champlain Basin, in the Memphremagog Basin (proglacial Lake Memphremagog), and in the Connecticut Basin (proglacial Lake Hitchcock).

Another classic previous work having to do with deglacial history of a large portion of the State is by Chapman, 8Chapman, D.H., 1937, Late-glacial and postglacial history of the Champlain Valley. American Journal of Sciences 5th Series, 34: 89-124. Also, appearing as a report of the Vermont State Geologist. as substantially referred to below. Whereas Chapman focused primarily on strandlines for proglacial Lake Vermont and the Champlain Sea in the Champlain Basin, he recognized that Lake Vermont expanded and closely followed the ice margin during the recession of the ice sheet, leading him to postulate about ice margin positions in the Champlain Basin.

Chapman’s study of proglacial Lake Vermont is remarkable for several reasons. Not only did my work in the 1970s serve to confirm his findings on the strandline history of standing water bodies in the Champlain Basin, albeit in more detail with slight strandline differences, but in re-reading both his reports, the first published in the American Journal of Science and as well his subsequent report for the Vermont Geological Survey, I have come to realize that he likewise was struggling to decipher the ice margin history part of the story, about which his reports offer important insights. Chapman recognized, as did others before him, that as the ice sheet retreated in the Champlain Basin, in what is now referred to as a “reverse gradient setting,” 9A “reverse gradient setting” refers to recession of the ice margin taking place down a physiographic slope, such that meltwater is impounded along the ice margin. Such settings are now recognized as being especially prone to destabilization of at least portions of the ice sheet. that as a consequence most of the receding ice sheet was continuously fronted by standing water of Lake Vermont, which lowered from Coveville to Fort Ann to Champlain Sea levels. 10 The terms for proglacial Lake Vermont stages Coveville and Fort Ann are now part of a traditional lexicon. More recent research reports( as discussed below) in Quebec have suggested the name Lake Candona to replace Lake Fort Ann, and in New York by Franzi et al(2025) suggest the names Lake Abenaki and Lake Akawasasne for Coveville and Fort Ann, respectively. In my opinion, this research and revision, including the introduction of new names has merit. To minimize confusion, the old, classic names are used here.

Chapman refers to ice margins being continually “bathed” in water. This has major implications:

- One would expect that ice margin features, such as stagnant ice deposits and proglacial lake features, such as kame deltas, would be intimately and closely associated with each other at elevations close to the proglacial water levels during ice recession. This is substantiated by VCGI mapping, but is an aspect deserving much closer, more detailed field study.

- Whereas Chapman and most of us in this field have traditionally tended to think of a “Coveville time” and a “Fort Ann time, ” this is not correct, as is made apparent by the fact that these strandlines formed at different times during ice margin ice margin recession, as specifically recognized by Chapman. Franzi et al, 11 Franzi, D., Carl, B.S., and Pepperstone, H, 2025, Late glacial lake and marine strandlines in the Ontario, St. Lawrence, and Champlain lowlands, USA and Canada, record steadily decreasing water levels interrupted by breakout floods; manuscript in press with Quaternary Research and citations not yet available, 45 pages. These authors have re-examined the Lake Vermont strandlines in New York in detail, and has determined that a) these are diachronous, meaning that the ages of individual strandlines become progressively younger northward as the ice sheet receded, and that b) for a variety of reasons, the level of individual strandlines varied through time. Franzi proposes re-naming Coveville Lake Vermont as “Lake Abenaki” and Fort Ann as “Lake Akawasasne.” Franzi’s diachronic concept for strandlines is significant and applies as well specifically to ice margins T6 and T7. The T6 ice margin is marked on the Statewide map in close association with Coveville Lake Vermont. recognized the time-transgressive nature of Coveville and Fort Ann deposits, introducing a new way of thinking or “paradigm,” referring to strandlines as being “diachronic.” This thinking applies as well to ice margin levels and times, as explored in this report. The findings presented here indicate that ice margins levels and times were closely associated and that both can be thought of as being diachronic.

- Franzi et al also suggest that the Lake Vermont water ”levels” were not a simple two step recession from Coveville to Fort Ann levels but instead involved fluctuating water levels during progressive lowering. This is supported by VCGI mapping here by the identification of the “step-down sequence” of receding ice margins and associated water levels of numerous and extensive proglacial water bodies, “like water levels in a slowly draining bathtub.” This likely took place along with ice margin oscillations, which thus helps to account for variability in water levels as suggested by Franzi.

Fred Larsen, who was a colleague and friend at Norwich University, published multiple articles about glacial geology of east-central Vermont, including in the Connecticut and Winooski Basins and associated tributaries. For example, one of his reports deals with the deglacial history of Lake Hitchcock. 12Larsen, F.D., 1987, Glacial Lake Hitchcock in the Valleys of the White and Ottauquechee River, east-central Vermont; Guidebook for Field Trips in Vermont, NEIGC V2,pp 30 – 52 . Several items of his report merit note here. One is a statement(p 32): “I believe that the model of three drift sheets in Vermont and New Hampshire is untenable and that the surface till of New England resulted from the advance and retreat of one ice sheet, the Late Wisconsinan Laurentide Ice Sheet.” Larsen is referring to and taking issue with the three-fold glacial history interpretation by Stewart and MacClintock. . Larsen also suggested that whereas the recession of the ice sheet in the Connecticut Basin in Massachusetts and southern Vermont(south of the Putney area) was by northward retreat of an active ice margin, the lack of a radial pattern of striations on the west side in Vermont north of Putney led him to conclude that, “deglaciation of the Connecticut Valley north of Putney was by a stagnant tongue of ice.” These observations are especially pertinent with regard to the finding reported here of “Disconnections” of the ice sheet in the Connecticut Basin resulting in en masse stagnation.

Larsen’s observations regarding ice stagnation in the Connecticut Basin continues a long standing debate, as noted above, dating back to the 1930s, to Flint’s interpretation of a stagnant “Connecticut Glacier.” This debate has been more recently reviewed by Thompson et al in New Hampshire , as discussed in more detail below.13 Thompson, W.B. et al, 2017, Deglaciation and late-glacial climate change in the White Mountains, New Hampshire, USA, Quaternary Research, V 87, pp 96-120. However, whereas Larsen addressed deglacial history of the Connecticut Basin in terms of the development of proglacial lakes, he did not delineate the receding positions of the ice margin across the region.

The most substantial recent work in Vermont has been by Stephen Wright, former Senior Lecturer in the Geology Department at the University of Vermont, and his colleagues George Springston at Norwich University, and John Van Hoesen at Green Mountain College. These researchers have studied the glacial geology of many locations, generally in north-central Vermont, mostly in the upland areas, plus scattered other locations in the State. Most of this work has been for the Vermont Geological Survey as reported in open-file reports for the Survey which are available online. In the course of this present investigation I have reviewed many of their reports. Specific reference is made to their individual reports in the text below as appropriate.

In general, I have been impressed by the careful attention to detail by Wright and colleagues, which I admire and respect. Their reports provide specific documentation of different types of depositional and erosional features, as for example, stagnant ice deposits, ground moraine, deltas, striations, etc.. With regard to glacial history, these authors identify ice margin positions by inference with reference to proglacial lakes, similar to the approach taken by Chapman for the delineation of ice margin positions associated with Lake Vermont. Unlike the work reported on here, Wright et al, do not attempt to specifically construct a deglacial history based on ice margin features, per se.14I shared an early draft of this report with Wright, intentionally avoiding specific reference to his findings and the work of his colleagues in order to not “tread on toes” and because it had been my hope that we could collaborate together on this present report whereby he would add information from his studies as he best saw fit. Unfortunately, as discussed below, that collaboration cannot happen, and as a consequence this present report lacks what no doubt would be helpful insights from Wright and his colleagues. 14 I shared an early draft of this report with Wright, intentionally avoiding specific reference to his findings and the work of his colleagues in order to not “tread on toes” and because it had been my hope that we could collaborate together on this present report whereby he would add information from his studies as he best saw fit. Unfortunately, as discussed below, that collaboration cannot happen, and as a consequence this present report lacks what no doubt would be helpful insights from Wright and his colleagues.

A sidebar example of the way in which Wright and colleagues have approached the positioning of ice margins in deglacial history is given by a recent report for the Winooski Basin(Wright et al, 2024): 15 Wright, S. F., et al, 2024, The Glacial, Late-Glacial, and Postglacial History of North-Central Vermont, 20 Years of New Work; Field Trip Guidebook for the 85th Reunion of the Northeast Friends of the Pleistocene, 58 p. 9

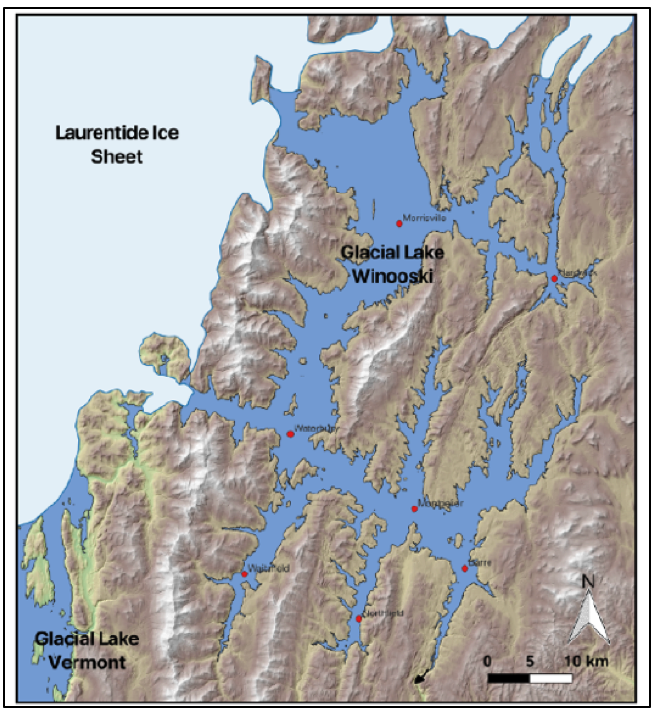

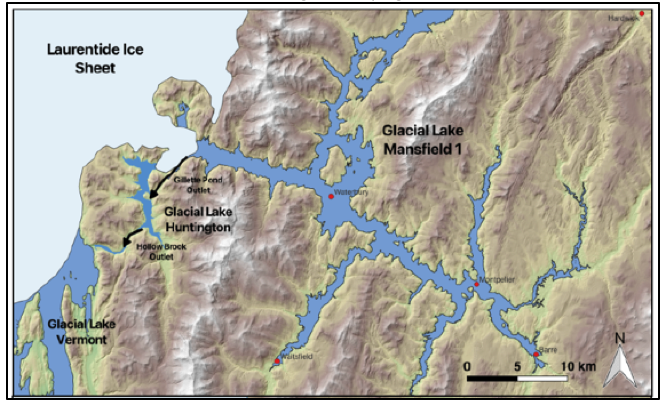

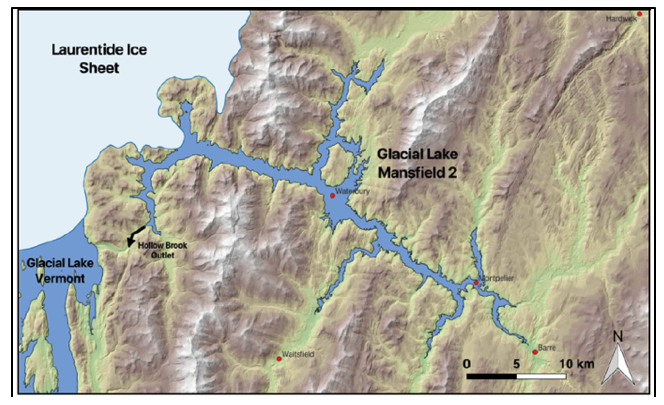

As shown on the following maps, proglacial water bodies are identified, their extent delineated, and their outlet ice margin positions located, which enables them to infer approximate ice margin positions:

- Lake Winooski with drainage southward into the Connecticut Basin at an outlet at Williamstown Gulf:

- Lake Mansfield 1, with an ice dam further westward and an outlet at Gillett Pond with drainage westward into a lake in the Huntington Basin, which in turn drained across the divide between the Huntington Basin and Hollow Brook Basin, with further drainage westward into Lake Vermont in the main Champlain Basin marked by a delta at the Coveville level at South Hinesburg.

- Lake Mansfield 2, with an ice dam still further to the west, and a lower nearby outlet at the divide between the Huntington Basin and Hollow Brook Basin, likewise with drainage into Lake Vermont at the Coveville level at South Hinesburg :

- Coveville Lake Vermont, with ice dam gone:

As shown by the preceding sidebar, the authors approximate the locations of the ice dam positions based on the westernmost extent of strandline features, and what makes sense physiographically and geologically. This approach has merit but differs from the methodology used here, which delineates deglacial history and associated changing ice margin positions based on both ice margin features and proglacial water body and drainage features, thereby providing more detailed and specific information and a more complete deglacial history. Both methods are imperfect and have their difficulties and uncertainties, and obviously a more complete understanding comes from their usage together.

Footnotes: