Thanks to my undergraduate mentor, Professor John Moss at Franklin and Marshall College, who got me started in my love of everything glacial, I began my graduate studies at the University of Michigan under Professor Don Eschman. Michigan at that time had a wonderful, diverse program in Pleistocene studies. In my first year I took a course in palynology with Botany Professor Bill Benninghoff. Not only did Bill put me in contact with the Icefield Ranges Research Project in the Yukon where I spent two summers on the Kaskawulsh and Hubbard glaciers for my Master’s thesis dissertation, he gave me an understanding of vegetation associated with the receding Pleistocene ice margins. One of Don’s colleagues was Professor John (Jack) Dorr, a vertebrate paleontologist whose entire career was involved with a search for fossil evidence for early human migration into North America via an interior migration route between the Cordilleran ice sheet and the Laurentide ice sheet. Under the tutelage of Don, Bill, and Jack, plus Profs Bill Kelly and Ed Goddard, my PhD dissertation became a study of the late Pleistocene of southwestern Alberta. My focus was on the evidence related to the deglacial history of the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets, which clearly established that these two ice sheets had coalesced and remained joined until late glacial times, dispelling the theory that early humans initially had migrated into North America via an interior open, ice free corridor, contrary to Dorr ‘s belief. Nevertheless, as personally disappointing as my findings were to Jack, he signed off on my Dissertation.

Early human history thus has long been a personal interest. In general, the prevailing theory was that late Pleistocene human migration was driven by the availability of large game, such as musk ox, caribou, wooly mammoth and mastodon, that such animals could be taken relatively easily and thus served as a convenient and important food source, and further that such animals shadowed the shifting grasslands and woodlands associated with both the advancing and receding ice sheet margins. Thus, early human migration may as well have shadowed the receding ice margins. Early humans were effective killing machines, decimating game supplies, and thus were continuously migrating in search of food for the large game species which were relatively easily taken by spears, using stone projectile points.

By classical thinking, the earliest was a Paleoindian Clovis culture, as reflected by fluted projectile points. Clovis was long lasting, and thus such finds at archaeological sites do not necessarily imply the close presence of the ice sheet. Nevertheless, the lithic derivation of projectile points provides evidence for alternative possible migration routes.

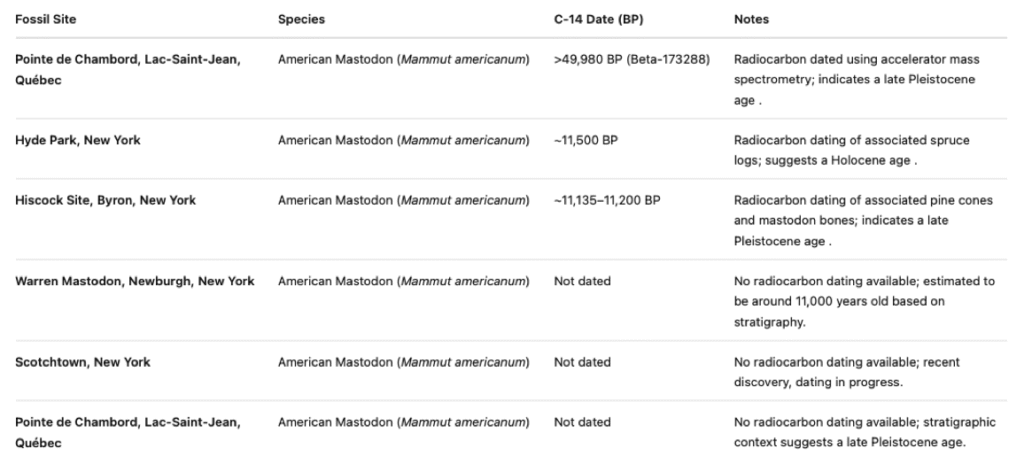

Mammoth and mastodon remains have been found in Pleistocene deposits in various places in eastern North America, including in Vermont, Quebec, New York, and Nova Scotia. The following table gives some example C 14 dates, thanks to ChatGPT:

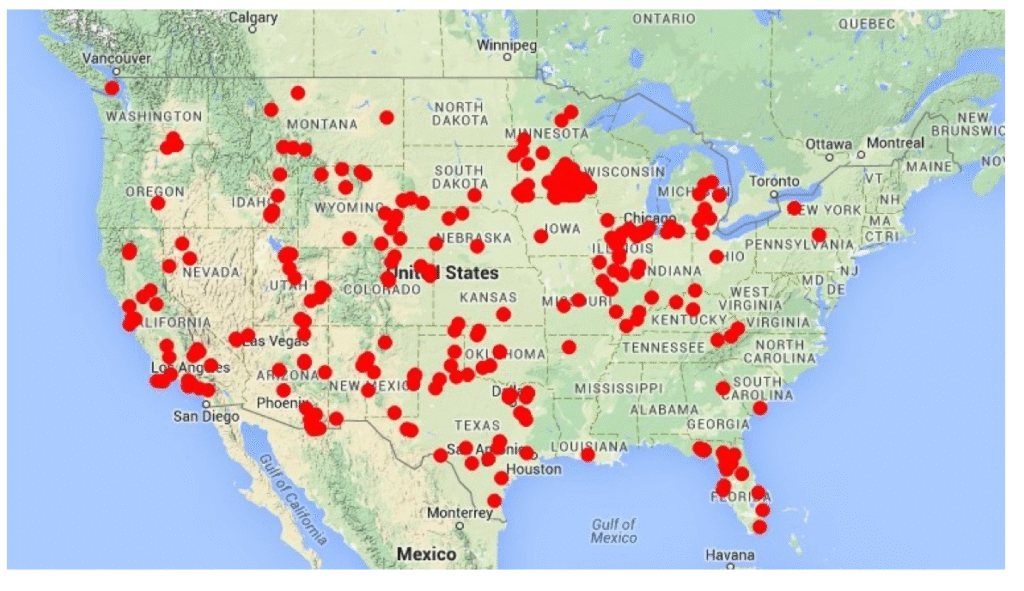

The following ChatGPT provided map shows mammoth finds in the United States portion of North America:

And for mastodons, again from ChatGPT:

Obviously, these species were widespread. In general, mammoth diets were predominantly grasses and mastodon diets were tree vegetation.

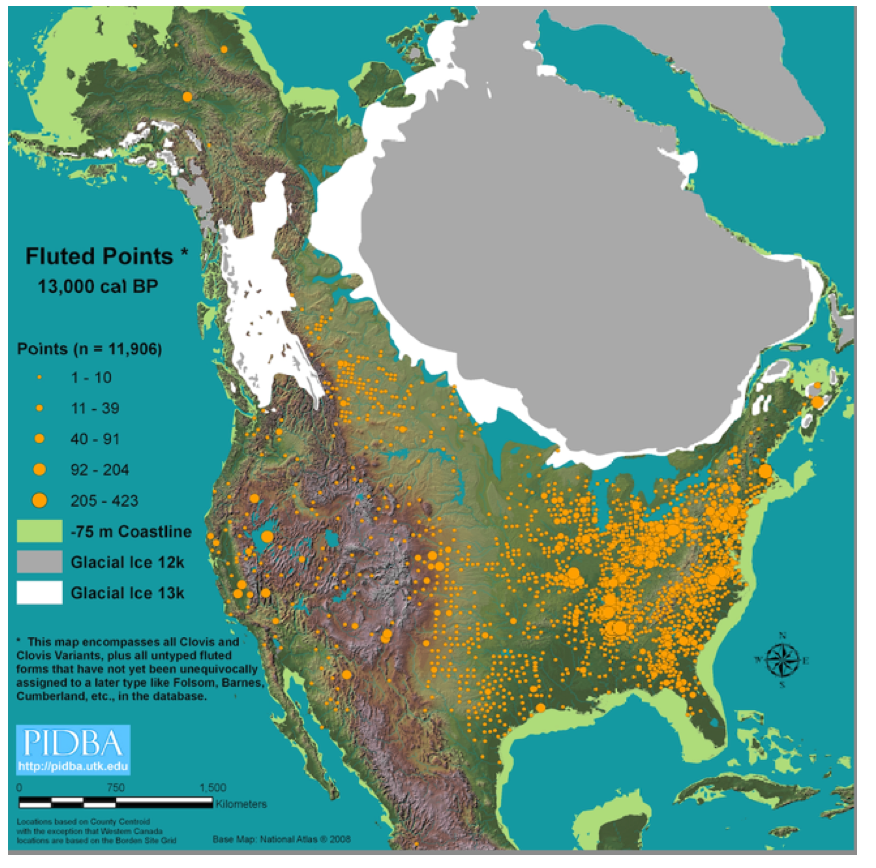

And the following ChatGPT map provides information about Paleoindian (Clovis) sites, known, presumed, or inferred to be about 13,000 years BP:

Whereas I take issue with the delineation of both the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheet margins on the above map, specifically the suggested open corridor between these ice sheets and as well the configuration of the ice margin in the northern New England area, the above maps are given here simply as a means of underscoring and giving a sense of the relevance and importance of the findings of this VCGI study to the issue of Paleoindian presence and migration.

One of the side benefits of this present VCGI study is that the identification and delineation of ice margins and associated water bodies gives a sense of possible migration routes and more favorable locations for further search for Paleoindian sites in Vermont. Obviously more study is needed, but the combined input from glacial history with archaeology would seem to offer potential benefits.

I am not an archaeologist and am on speculative thin ice, but I am intrigued by the relationship between glacial history and early human presence in Vermont. My understanding is that two sites in Vermont represent the early Paleoindian (Clovis) presence. One is an upland site near Ludlow and the Okemo ski area, referred to as the Jackson Gore site, and the other is a lowland site near Williston, known as the Mahan site.

The Jackson Gore site has been documented by classic fluted (Clovis?) spear tip points made of various lithologies, some of which have been identified as coming from Maine and Pennsylvania. This suggests, perhaps, a migration route into Vermont from the south via the Connecticut Basin. This site lies on the eastern side of a low col in the Green Mountain ridge line which my VCGI evidence suggests became deglaciated in T3 time, at stagnant ice deposits closely associated with the second of three “Disconnections,” in the Middle Connecticut Basin, as discussed in detail below. From my perspective, an early human migration pathway into Vermont may have been northward, up the Middle Connecticut Basin in T3 time, with the Okemo site favorably located, just below what would then have been an outlet glacier for the Laurentide ice sheet in the Champlain Basin to the west. The Disconnection of the ice sheet in the Lower and Middle Connecticut Basins likely would have opened an ice free corridor in much of the Connecticut Basin. So far as I am aware, no absolute age dates have been established for the Jackson Gore site, but early Clovis is estimated to have been about 11,000 – 12,000 years BP. Thus, it is possible that this site reflects the close presence of the ice sheet. Interestingly, mammoth remains have been found nearby at Mount Holly, which is within the T3 ice margin. These have been dated at about 10,860 BP and thus may be slightly younger than Jackson Gore, again in close proximity to the ice margin.

The Mahan site is regarded as the earliest lowland Paleoindian site in Vermont. I understand from the Web that archaeologists speculate that this site may have been a summer base camp where a group of 25–40 individuals stayed for an extended period. It is said to have offered strategic advantages: a slight hill for elevated views, a warmer microclimate, and easy access to water, game, and edible plants. The site is located close to the late T6 and T7 margins, when and where the ice sheet still occupied the Champlain Basin to the west, flanked by a narrow corridor of Lake Vermont, extending into the Winooski Basin shortly after Lake Mansfield in this basin had drained. Conceivably, stagnant ice masses may still have been present, as for example in a deep kettle hole referred to as Mud Pond. Again, according to the Web, the lithic origin of projectile points at the Mahan site includes local materials (Champlain Valley & Vermont sources, including quartzite and chert from nearby deposits, likely from local river cobbles and bedrock outcrops), and as well non-Local, exotic materials:

- Munsungan chert (from northern Maine, (~300–400 miles away)

- Jasper and rhyolite from Pennsylvania (~400–500 miles south)

- Possibly other fine-grained lithics from New York and Québec

Thus, the Mahan site may represent alternative or multiple migration pathways, along:

- the Winooski Basin from the Connecticut Basin, possibly in T4-T6 time,

- along the Champlain Basin narrow open water corridor along the T6 and T7 ice margin northward from the Hudson Basin in New York via the Coveville or Fort Ann open water corridors, and/or

- southward from Quebec in T6 and T7 time, perhaps along either the western margin of the Champlain lobe from the Ontario Basin, associated with proglacial Lake Iroquois, or southward along the lobe eastern margin in T7-T8 time, and beyond.

Other Paleoindian sites have been identified in Vermont. For example, the Mazza site in Colchester is at an elevation which places it close to the Champlain Sea. However, this site is located along Sunderland Brook which was eroded into the Champlain Sea delta, suggesting that the age of this site postdates T8 or early Champlain Sea time at the marine limit. Thus, Paleoindian presence in Vermont likely extended over a substantial time, perhaps shadowing ice margin recession from T4 to T8 time.

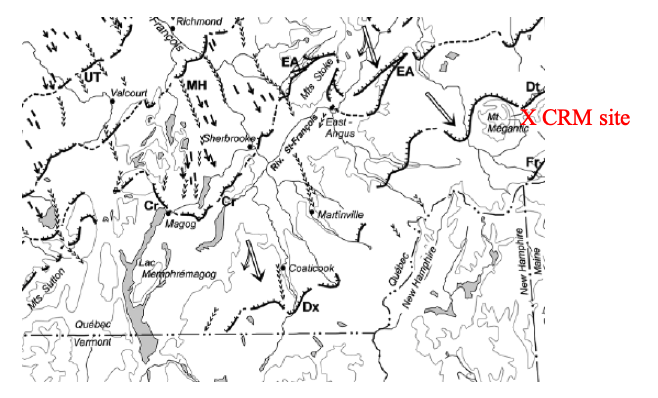

Multiple Paleoindian sites have likewise been identified in Quebec. The Cliche-Rancourt–Mamsalhabika (CRM) archaeological site deserves brief mention. According to ChatGP, this site reportedly is located on a sandy terrace along the Araignées River in the Lac Megantic region near the Maine border. The following screenshot, taken from Parent et Occhietti (1999, Figure 2), shows the approximate location of this site relative to the recessional moraines in southern Quebec:

As can be seen, the CRM site is close to a moraine identified as Ditchfield (Dt), which approximately corresponds with the Dixville (Dx) moraine, the latter of which is correlated with the T4 ice margin. Of course, both the Clovis projectile point chronology and the T time chronology presented here represent time spans which overlap but do not establish precise time equivalence. Clovis time represents a broad time range, such that occupation of the CRM site may postdate the Dt, Dx, and T4 times. But it is possible that the CRM site was initially occupied close to T4 time. Whereas according to VCGI mapping the T4 margin would not have opened an easily traversed migration route from the vicinity of the CRM site to the Mahan and Jackson Gore sites, if as is here believed that the ice margin recession was rapid, such that rapid recession through T5, T6,T7, and T8 times may have opened more easily traversed routes from Quebec to the Mahan and Jackson Gore sites.

The CRM site is said to include stone tools and cultural traces dating back ~12,000 years, connected to early human occupation associated with the recession of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. Projectile points include a mix of local and long-distance provenance raw materials, the main ones being Red Munsungun chert (northern Maine), Rhyolites from northern New England, notably Mount Kineo (Maine) and Mount Jasper–Jefferson (New Hampshire) , and local volcanic rocks (rhyolite / trachyte / phonolite) from the Montagne de Marbre area. Thus, a southwestward migration route along the ice margin from Quebec into Vermont may have existed. The ice margin positions which are identified in this VCGI report provide more specific information than previously available about possible early human migration pathways into and around Vermont,and deserve further scrutiny in this context.

Early human history in Vermont is an intriguing sidebar to this deglacial ice margin recession history, going beyond my expertise and the scope of this report. But it seems obvious that a further dialogue might be productive. From my perspective, hiking, canoeing, or rafting explorations on proglacial Lake Hitchcock in the Connecticut Basin, on Lakes Winooski or Lake Mansfield in the Winooski Basin, or on the Fort Ann or Champlain Sea corridors in the Champlain Basin would have been fabulous experiences, with dramatic vistas, in some places (such as at Ice Tongue Groove locations) rivaling or exceeding today’s Niagara Falls, with the ice sheet as a backdrop. While it is likely that Clovis peoples had survival, and not tourism in mind, I would imagine that scenery would have been an observable bonus attraction.

Franzi proposes re-naming Coveville Lake Vermont as “Lake Abenaki” and Fort Ann as “Lake Akawasasne” in honor of Native Americans, which in my view is quite appropriate, although the Akawasasne and Abenaki peoples generally are regarded as younger than Paleoindian time, postdating Champlain Sea time.