As indicated above, I feel compelled to speak to the issue of global warming. This report is about the end of the “Ice Age” in Vermont, which in the larger sense is a story about global warming. When I was in college and first being introduced to the discipline, in “Geology 1,” I learned about one of the classic principles of geology, the so-called “Principle of Uniformitarianism.” This Principle states that “the present is the key to the past” – meaning that if we want to understand the geological past we need to look at modern day environments, applying this understanding to the past geologic record, to deduce its meaning and history. It strikes me that today, as has been suggested by others regarding the concern for global warming, having a better understanding of the past may help us to understand the present – the Principle of Uniformitarianism in reverse.

Present day ice sheets are difficult to study, especially at their base, beneath the ice sheet, even at their margins. In a sense, this is why much of the literature about modern ice sheets involves digital modeling. As suggested elsewhere herein, this is dangerous territory for modeling, which necessarily is based on substantial assumptions about “what is going on down there.” Thus, studies of past glaciation can be helpful and important.

My mapping has shown that as the ice sheet in Vermont retreated it encountered conditions that resulted in rapid, accelerating, and destabilized ice margin recession, marked by calving ice shelves and associated features, at multiple times. Also the evidence here indicates massive stagnation on local and regional scales. 1By “destabilization” I refer to the effect of standing water in a reverse gradient environment along and beneath ice sheet margins , as reported in substantial glaciology literature on modern ice sheets, resulting in rapid ice margin retreat, lowered ice sheet levels, steepened gradients, altered streamlines, accelerated ice flow, and calving ice shelves. Diverse evidence for this is found in all the major basins but is especially prominent in the Champlain Basin, with calving marked by multiple types of distinctive ice margin features. Evidence for “massive stagnation,” meaning when and where large portions of an ice lobe, stagnated en masse in place, is documented by ice margin features here termed “Scabby Terrain,” which is believed to have been associated with “Disconnections,” a term introduced in recent literature in regard to ice masses becoming separated from the parent ice sheet or glacier due to thinning of the ice over physiographic divides or penetration of standing water along the perimeters of “Disaggregated” ice margins. This has implications bearing on present day ice sheets and glaciers, global warming, and sea level rise. In essence, I believe that various findings presented in this report about Vermont’s surficial geology tell a story about the “death” of a significant part of the Laurentide ice sheet which is relevant today in our modern era of human induced climate change.

My concern about global warming has an existential quality to it, the fear that my grandchildren, or perhaps their grandchildren – who knows how fast this is coming? – may be faced with possibly cataclysmic and perhaps irreversible conditions for which their forebears – i.e., my grandparents, my parents, and me – were largely responsible, of course in a collective, generational sense. I’m not one to shout out that “the sky is falling,” but I am one to say that it looks to me like “the puddle is rising.” In a sense, for me personally, in my belief system, the question is not so much if but when, the only question being how fast this is happening and whether or not we have time to make corrections before it is too late.

I am not an expert on global warming or Antarctica or Greenland. But I did cut my teeth in the Arctic, and have a sense of the power and significance of meltwater. This present report, while not answering the question about global warming and its speed, or ice sheet collapse, provides insights which bear on present day global warming concerns. Thus, at the risk of overstepping my expertise, getting too far out on “thin ice” so to pun, the following gives an overview of the evidence reported here bearing on modern-day global warming:

- Physiography of the terrain beneath the Laurentide ice sheet in Vermont was important relative to the deglacial history. As the ice sheet thinned, ice thicknesses across physiographic divides caused “Disconnections” by which major sectors of the ice sheet downgradient from these divides became separated from the parent ice sheet, resulting in en masse stagnation, as documented by distinctive ice margin features referred to here as Scabby Terrain. This occurred at three successive times in the Connecticut Basin of Vermont, together accounting for the sudden “collapse” of about 40-45 per cent of the Vermont ice sheet.

- The recession of the ice sheet in Vermont took place predominantly in a reverse gradient setting, whereby the ice margin was constantly in contact with meltwater during its recessional history, and increasingly and ever more substantially so with time. Such settings favor rapid, accelerated recession because ice margins are continually bathed in free and confined water. Such water is thermodynamically effective in causing and assisting heat transfer, resulting in extensive and rapid ice melting, closely associated with the physiographic configuration of the physiographic “Bath Tub.” Water beneath the ice sheet likewise serves as a lubricant accelerant, physically increasing the speed of ice flow. And standing water in front of the ice sheet serves as a physical buttress against ice margins, whereby lowering of standing water body levels, especially when happening suddenly and substantially, results in an alteration of the ice sheet’s physical equilibrium between accumulation, ablation, ice flow, and ice margins. All of these factors and effects lead to disequilibrium with lowered, receding ice margins, increased ice surface gradients, transformation of portions of lateral margins to frontal margins, and accelerated ice flow toward areas of lowered standing water levels via ice streaming and calving.

- Ice Marginal Channels mark the early time of ice sheet recession in T3/T4 time and represent evidence of meltwater penetration beneath the ice sheet margin in the “Nunatak Phase” and the early portion of the “Lobate Phase.” Ice margin features associated with the earliest Lobate Phase are correlated with the White Mountain Moraine System (WMMS) in New Hampshire, which is documented as representing a significant readvance. As discussed in the “Epiphany” section of this report, it is hypothesized that whereas the recession of the ice sheet may have been generally oscillatory in nature, the readvance may have been especially important as it may have served to warm basal ice when the ice sheet readvanced over warmed terrain, leading to conditions favorable for the formation of Ice Marginal Channels; in effect these may have formed as “outlet channels” across terrain protuberances for confined basal waters in a warmed basal ice polythermal setting.

- Further, the evidence from VCGI mapping here indicates that the Ice Marginal Channels and associated stagnant ice deposits at this early T3/T4 time and ice sheet level were a “hybrid” type ice margin consisting of both active and stagnant ice margins. 2As previously noted, essentially all ice margins mapped in Vermont here are regarded as hybrid typesThe evidence further indicates that such hybrid margins involved recession of the active ice margin to a new lower position occurred while ice was left remaining in stagnant ice deposits at a higher, earlier ice margin, showing the rapidity of the ice margin recession.

- Ice sheet recession following T3/T4 time is marked by Ice Marginal Channels, stagnant ice deposits, including kame deltas, Bedrock Grooves, Drainage Lines, and proglacial lakes, all of which are identified, described, and mapped here using VCGI. These features mark a characteristic step-down sequence of ice margin recession in the Lobate Phase, likened to “multiple rings in a slowly draining bath tub,” showing increasingly larger sectors of the ice sheet were fronted by larger, progressively more regional water bodies. Local proglacial lakes which progressively coalesced trough time, eventually led to large regional water bodies (such as Lake Vermont and the Champlain Sea). This observation is significant for present day global warming, as discussed further below, in that larger, coalesced regional water bodies have the capability of altering substantial portions of ice sheets.

- Further, the evidence indicates that these regional water bodies in Vermont were controlled or influenced by “externalities,” being entirely or largely outside of the ice sheet control, with the capability of imposing major, sudden water level or water flux changes.

- Three separate calving times or events are identified, the first related to the “Deep Lake” portion of the Basin, the second with the lowering of the water levels from Coveville to Fort Ann, concurrently with the drainage of Lake Mansfield in the Winooski Basin and the breakout of Lake Iroquois in the Ontario Basin into the Champlain Basin, and the third with the lowering of standing water levels from the Fort Ann to Champlain Sea levels.

- Standing meltwater was also effective at penetrating lateral ice margins, developing narrow, more or less open, “Disaggregated” ice margin water corridors, which expanded rapidly northward along the lateral margin, resulting in further destabilization by which the lateral margin became transformed into a frontal margin. As a consequence, the receding Champlain Lobe developed as a long convex shape, with ice recession entailing both significant lateral and longitudinal recession, meaning that the recession of the ice sheet was not a simple south to north progression of the ice margin as conventionally thought; such thinking is referred to below as a “paradigm trap.”

- Support for this rapid recession comes from evidence indicating that a) the earliest Lobate Phase T3/T4 ice margins mapped in Vermont correlate with the White Mountain Moraine System, which according to Thompson et al reportedly represents a readvance in Older Dryas time, dated at 13,800-14,000 years BP; and b) a second readvance occurred just prior to the final exit of the ice sheet from Vermont as marked by the T8 ice margin shortly after the opening of the Sea, which per Cronin et al dated at about 13,000 years BP. Thus, essentially the entire recessional history of the ice sheet as mapped here using VCGI marks both a late time in deglacial history and a very brief period of time.

The finding that the recessional history of Vermont is so young, in its totality representing a very late time in the recession of the Laurentide ice sheet , is quite unexpected and surprising. Likewise, the speed of the ice sheet recession is also remarkable. The message here for present day global warming concerns is that the deglacial history of the ice sheet recession in Vermont is multifaceted. It shows the effect of global warming on the Laurentide ice sheet and the importance of physiography and meltwater, in the context of interrelated deglacial history, Styles, and Glacial Dynamics. Of course, the point here is that this story provides clues in regard to the possible effects of today’s global warming on present day ice sheets.

With regard to modern ice sheets it seems clear that meltwater is a much bigger deal in Greenland than Antarctica, and thus Greenland might be more vulnerable. On the other hand the Antarctic ice sheet has its own vulnerability, particularly in that large parts of the Antarctic ice sheet include major calving ice shelves. The evidence from this study of the deglacial history of Vermont shows the development of such ice shelves and their associated grounding lines, in effect representing the ice sheet’s way of attempting to regain stability, which it turns out the Champlain lobe proved incapable of doing so in the face of sustained global warming. This evidence, perhaps, is the closest and best indication of a “tipping point,” leading to the inexorable demise of the Laurentide ice sheet in Vermont.

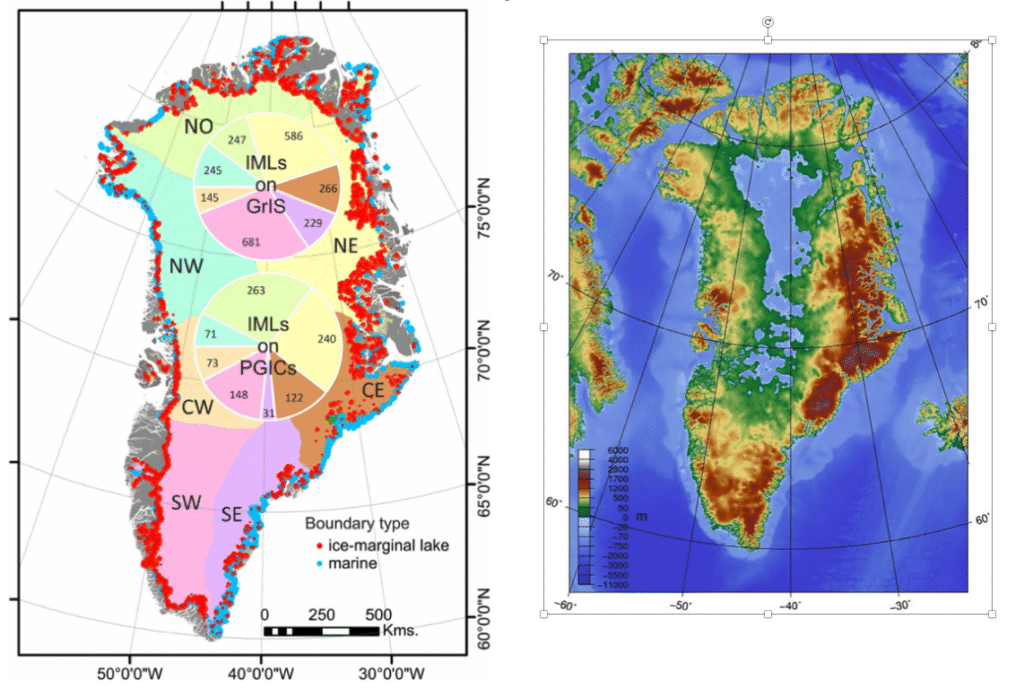

With the above perspectives in mind, I have reviewed some of the recent literature, especially about the present day Greenland ice sheet, just to get a sense of the possible relevance of Vermont deglacial history to global warming for this ice sheet. For example, Carrivick et al, 2022. 3. ://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/188509/1/Carrivick%20et%20al.%2C%20GRL_2022.pdf. provide an interesting overview of information about the Greenland ice sheet that strikes me as being especially relevant to the Vermont findings as just summarized. Their Figure 1 (shown below on the left ) illustrates the distribution of proglacial lakes around the perimeter of the Greenland Ice sheet, which is largely in a reverse gradient setting.

The map on the right above from another online source 4upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8b/Topographic_map_of_Greenland_bedrock.jpg gives a sense of the shape of the “bath tub” beneath the Greenland ice sheet, illustrating general physiography and the reverse gradient setting. A cursory look at the physiographic “bath tub” for Greenland reminds me of Vermont physiography. Obviously, the details between Vermont and Greenland ice sheet differ. The accumulation area for the Greenland ice sheet is in the interior area, which contrasts with Vermont where its basins were supplied by ice from the northern portion of the Laurentide ice sheet. This suggests that Disconnections such as occurred in the Connecticut Basin are less likely in Greenland. On the other hand, Greenland’s ice marginal lakes suggest the possibility of future Disconnections associated with further ice sheet lowering and development of more regional ponded water bodies, such as identified in Vermont.

Based on the lessons learned from my examination of Vermont deglacial history, it strikes me that the challenge is to look for critical “weakness points,” the “Achilles Heels,” so to speak, for Greenland, as suggested by the preceding summary overview, and described in more detail in this report. These might include, for example: a) buried physiographic divides at critical elevations, b) locations where lowering and coalescing standing water bodies may reach and open more regional lateral and vertical pathways that may result in sudden, perhaps major and irreversible water level changes or c) where the floor of the ice sheet may represent locations where ice masses might be vulnerable to crevasses penetration (such as by “hydrofracturing as discussed herein for the ice sheet at the “Middlebury Bench”) resulting in accelerated recession by calving. These issues have to do with the irregularity of the terrain, and the lowering hydrostatic base level associated with recession of the Greenland ice sheet. My understanding is that proglacial lakes around the Greenland ice sheet are showing signs of coalescing at elevations of 300-800 meters above sea level. Coalescence of proglacial water bodies along the ice margin is not a good sign, given that in the deglacial history of Vermont the evidence indicates that coalescence of proglacial lakes was part of the ice sheet’s demise.

Obviously, the above maps are far too general to pursue this issue in any serious, substantive way. It is impossible to understand the configuration of the bath tub in sufficient detail to examine and identify the possibility of critical weak points in Greenland with such general maps as depicted here. Perhaps the terrain beneath the ice sheet and along its margins is so irregular that the process as just described will take place quite slowly, so as to provide ample time for finding ways of reducing global warming. However, on the other hand, perhaps the “Achilles Heel” is closer than we would like. The question has to do with the tipping point where and when “all hell will break loose,” perhaps irreversibly.

The issue of global warming is increasingly appearing as part of my online news stream. For example, as discussed below, a recent NY Times article about the “crying” sounds of a “dying” glacier is haunting and compelling. 5www.nytimes.com/video/opinion/100000010222666/crying-glacier.html Another recent NY Times article about a glacier in Argentina 6www.nytimes.com/2025/08/07/climate/argentina-perito-moreno-glacier.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare speaks directly to the importance of the configuration of the terrain beneath a glacier or ice sheet, or in other words the shape of the “Bath Tub.”

Footnotes: