As noted above, physiography is an essential, foundational element for examining the deglacial history of Vermont using the “Bath Tub Model.” Thus, understanding Vermont and regional physiology is likewise essential. Whereas postglacial isostatic crustal rebound has altered present day physiographic elevations from those that existed during late glacial times, which is necessary to consider for purposes of mapping and correlating ice margins, present-day physiographic maps give a general sense of the physiography as it existed in late glacial times.

In general, ice margin features associated with specific times as were mapped in this study tend to wrap around, and closely conform to the physiography at different elevations. As indicated in the preceding, the evidence indicates that earlier ice margins associated with thicker ice may have been less sensitive to the physiography of the underlying terrain than younger ice margins with thinner ice. But, as stated above, even the earliest margins, such as T1 and T2,which are associated with “Disconnections,” show a relationship with physiography on a more major scale. Later margins, such as the T7 and T8, show remarkable sensitivity to very small topographic irregularities.

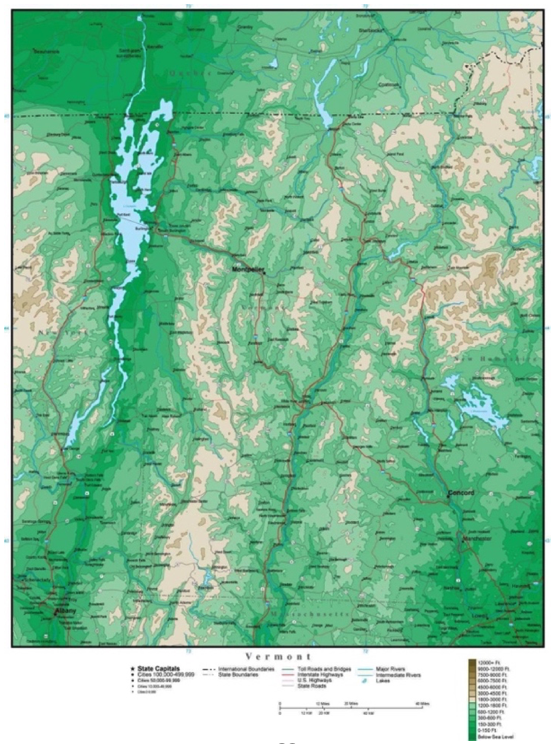

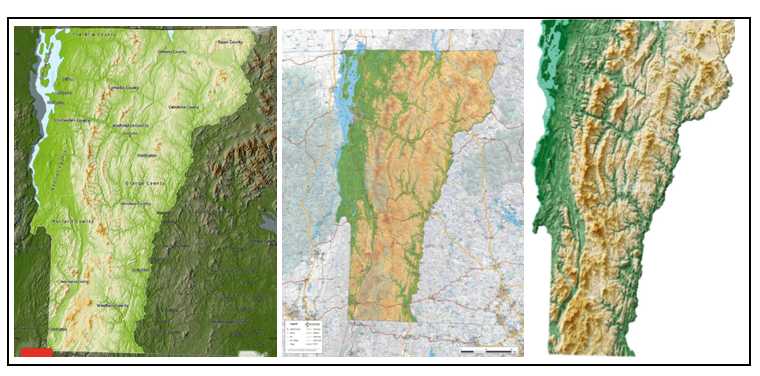

It turns out that understanding the terrain, getting a visual sense of it while mapping, especially when close up, as on VCGI maps, understanding how it varies within, across, and between basins, large and small, can be challenging. Therefore, examining physiography here is helpful as an introductory overview perspective. Numerous maps illustrating Vermont and regional physiography are reported online. While these may seem redundant, in general they provide information about subtle differences which can be important.

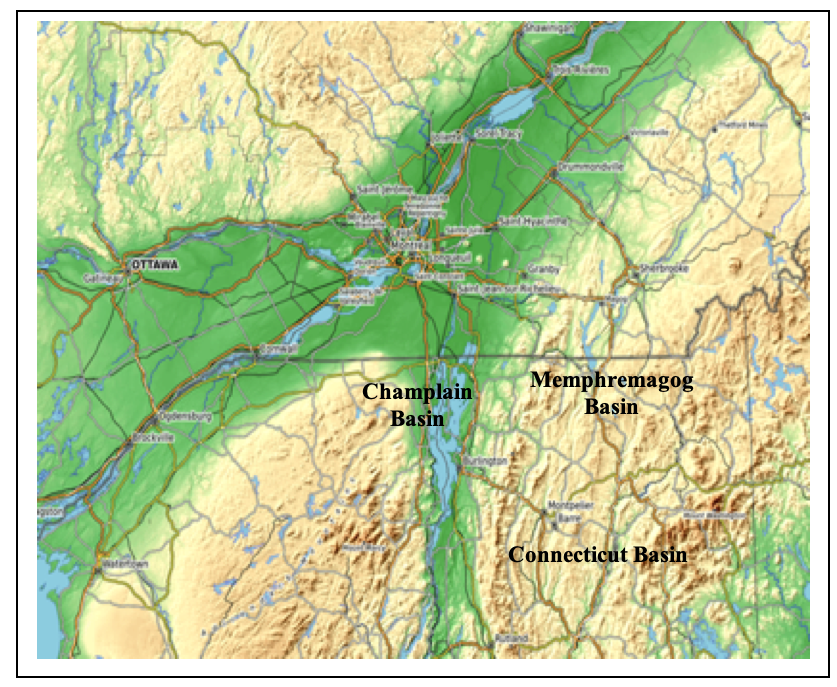

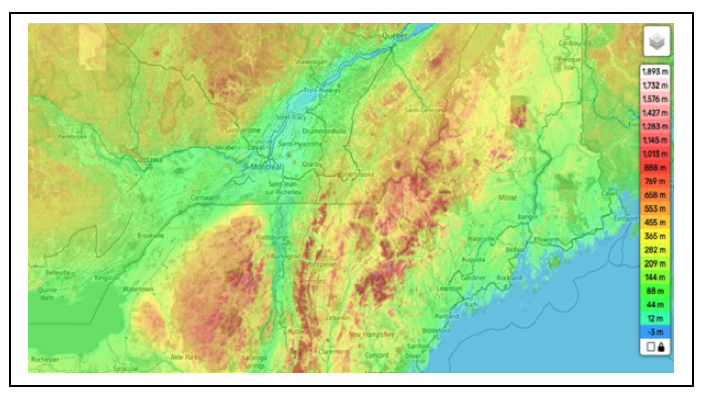

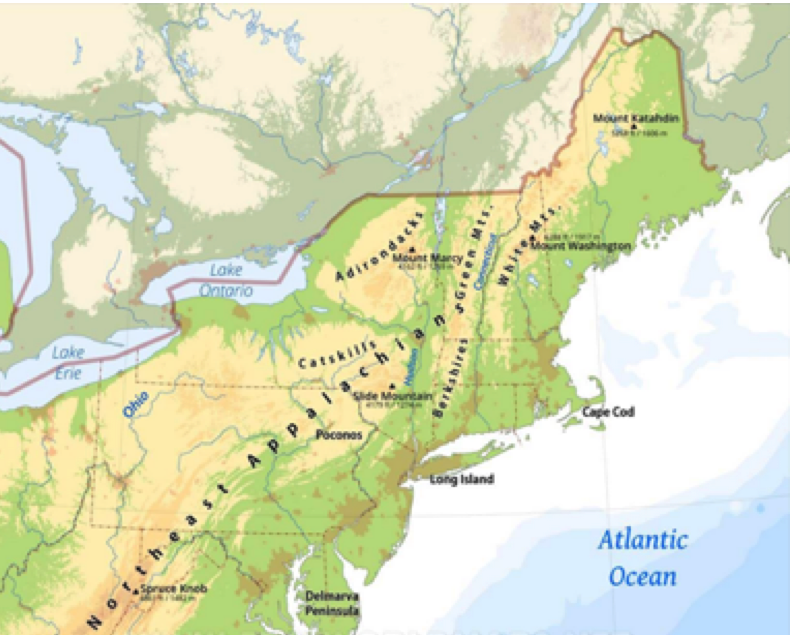

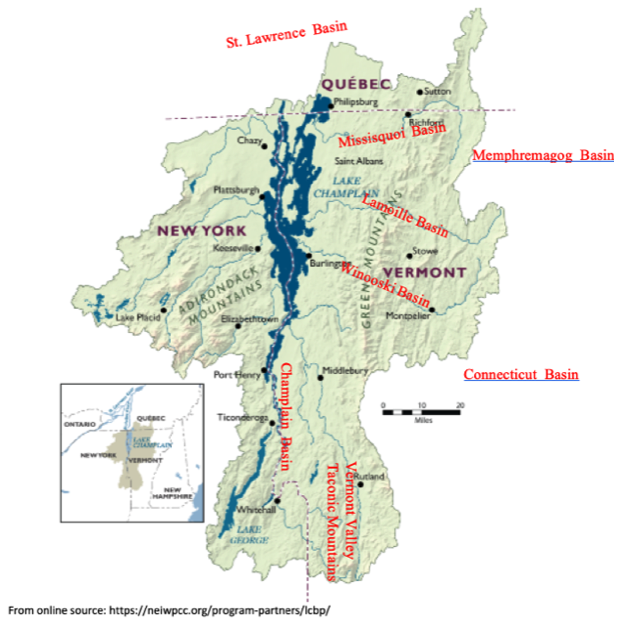

The following four maps from online sites give regional perspective. 1 https://en-ca.topographic-map.com/map-z4c3q/Quebec/?center=44.99106%2C-72.41132&zoom=15&overlay=0&base=2&popup=44.99257%2C-72.4072 , 2https:www.freeworldmaps.net/united-states/northeast/physical.html , 3 https://www.mapresources.com/products/vermont-digital-vector-contour-map-vt-usa-212176. The large size, low elevation floor, and open mouth to the north of the Champlain Basin favored a robust Champlain lobe, in contrast to the smaller, higher Memphremagog Basin. In contrast, uplands in the northern Connecticut Basin served to limit the southward flow of ice supply from the parent Laurentide ice sheet to the north. At relatively early times, the ice supply to the Connecticut ice mass came predominantly from the Champlain and Memphremagog Basins, ultimately leading to the demise of the ice mass in this basin when its supply became “Disconnected” by thinning ice across physiographic divides, as discussed below.

Many maps are more pictorial, but nevertheless give helpful insight about physiographic relationships. For example, the following map shows the Winooski and Lamoille Basins, which were occupied by tributary sub-lobes of the Champlain lobe, and which as deglaciation progressed became occupied by major proglacial lakes Winooski and Mansfield as delineated by Stewart and MacClintock and Springston et al, as discussed above.

Likewise, the following maps also are examples of more pictorial physiographic maps:

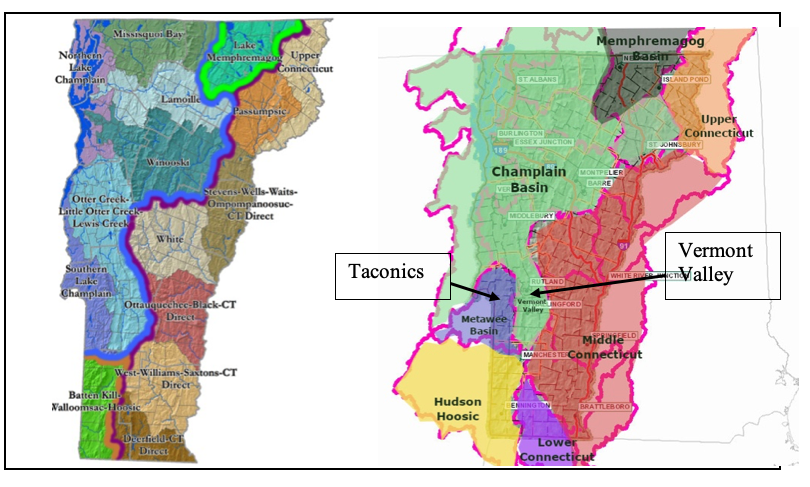

While not portraying physiography per se, the following maps show Vermont’s major drainage basins, which reflect and are dictated by its physiography: 4 https://dec.vermont.gov/watershed/map/program/major-basins

The map on the above right is the same drainage basin map as on the left, which is superimposed semi-transparently on a VCGI map of the State with the drainage basin tab turned on, with coloring to identify and demarcate regional drainage basins (purple colored lines). From the standpoint of deglacial history most of the State of Vermont can be divided into three major glacial drainage basins, specifically the Champlain, Connecticut, and Memphremagog, each of these occupied by discrete ice lobes, with small portions in the Metawee and Hudson-Hoosic Basins in the southwest corner of the State. For reasons explained below, the Connecticut Basin is here divided into Lower, Middle, and Upper portions. Also shown is the “Vermont Valley,” a colloquial name given for the long, low extension of the Champlain Basin between the Green Mountain front and the Taconic Mountains in the southwestern sector of the State.

The following map likewise is helpful in regard to the Champlain lobe, which was the most substantial ice lobe in Vermont, for its closer view of the Champlain Basin. The physiography of this basin was especially important in the State’s deglacial history:

As just mentioned in the preceding, the southern headwater area of the Champlain Basin bifurcates into two portions, specifically the lower Lake Champlain Basin floor and the higher Vermont Valley, the latter again a colloquial term for the relatively deep valley extending southward from the Rutland area to the Bennington area, separated from the Champlain basin floor to the west by the Taconic Mountains. The southernmost extent of the Champlain Basin in the Vermont Valley is near Manchester, south of which the Vermont Valley is in the Metawee and Hudson-Hoosic drainage basins. Also marked on the map for general reference are other neighboring sub-basins.

As a sidebar:

As deglaciation proceeded from the glacial maximum, the developing nunatak and ice lobe margins in Vermont were affected and largely governed by physiography, the primary lobes being in the Champlain, Memphremagog, and Connecticut Basins as depicted on the above physiographic maps. As noted above, the Champlain lobe was the largest, with the lowest floor and most open connection to the north, meaning it was directly fed by the parent Laurentide ice sheet to the north, and therefore the most robust. The floor of the Champlain Basin extends southward for over 100 miles from the Quebec border to its divide with the Hudson Basin, in the vicinity of Whitehall, New York.

The eastern margin of this lobe was against the foothills and the relatively steep front of the Green Mountains, which is broken by the major westward draining Missisquoi, Lamoille, and Winooski Basins, and other, smaller basins. As previously noted, the recession of the ice margin along the eastern side of the basin was marked by a distinctive Style, reflecting the progressive and incremental ice margin recession resembling closely spaced rings on a “Bath Tub”, characterized by a step-down sequence of stagnant ice deposits, drainage lines, and local proglacial lakes, giving way to regional proglacial Lake Vermont. This step-down sequence had a very complicated history related to the irregular topography of the foothills. One consequence of this is that the identification of Coveville Lake Vermont and its distinction from local upland lakes is very difficult and challenging.

Likewise, again as already noted, the smaller Memphremagog Basin was open to the north for a direct connection with the parent ice sheet, with a relatively flat, low gradient floor but at a relatively high elevation as compared to the Champlain Basin. This basin is marked by a massif in its southern portion, broken by long, narrow valleys extending to and across divides with the Connecticut and Lamoille Basins to the south. In a sense, the shape of the Memphremagog Basin is hand-like, with the palm representing the basin floor, with long and narrow drainage fingers. Unusually deep, “over-deepened” lakes occupy the floor of many of these fingers. The analogy with the Finger Lakes of New York, both physiographically and geologically, is remarkable. The present day basin floors of these over-deepened basins are at elevations below the present day Lake Memphremagog, thus representing deep, closed basins which, along with many other unusually deep lakes and ponds in northeast Vermont, served to hold isolated blocks of long lasting ice during deglacial times. These contributed to an ice margin Style, as explained below, and referred to as “Everything, Everywhere, All at Once and Continuing.” This same, relatively complex Style also was found in the foothills of the Champlain Basin in conjunction with a calving ice margin. The point being made here is that ice margins were more complex than the traditional view of these as simple lines on maps.

Also as previously noted, in contrast, the Connecticut Basin, while substantial in size, representing almost half of the State, is marked by significant uplands to the north and thus the ice mass that occupied this basin was less well connected to the parent ice sheet. This difference had significant impact on the deglacial history of the Connecticut Basin, at least for the Vermont portion. In particular, again as discussed below, the lowering of the ice sheet resulted in much and perhaps all of the ice mass in the Connecticut Basin, again at least in Vermont, becoming “Disconnected,” resulting in en mass stagnation of the ice mass at three successive times in different locations, governed by physiography. Also, a different type of Disconnection is identified in association with Lake Winooski, a large standing water proglacial lake in the interior uplands of the Winooski and Lamoille Basins.

Whereas the Connecticut Basin drains southward along the eastern portion of Vermont, continuing southward to Long Island Sound, the Champlain and Memphremagog Basins drain northward. As such, again as noted above, the generally northward recession of the margins of the lobes in the Champlain and Memphremagog Basins faced “reverse gradient” conditions. 5 Numerous publications in the glaciology literature identify “reverse gradient” environments as being especially vulnerable for destabilization, which may become irreversible as the ice margin retreats into areas where the depth of proglacial waters increases. Of course, the surface gradient of the ice sheet itself was generally southward, associated with the southward flowing ice, as was necessary for the nurture and feeding of these ice lobes by flow from “accumulation areas” to the downgradient “ablation areas” near lobe frontal margins. Thus, during recession of the ice sheet its frontal margins retreated northward, down the regional physiographic gradient related to the St. Lawrence lowland, and as a consequence, whereas meltwater drainage off the ice sheet during its retreat was southward, as marked by ice marginal drainage features along its margins, in the low areas of the Champlain and Memphremagog basins, the lower, frontal and lateral side margins of the ice lobes were associated with standing proglacial water.

The above physiographic maps give a helpful sense of late glacial terrain which is illustrative, supportive, and even predictive of detailed aspects of the deglacial history reported here. Ice margin features have been found at many elevation levels in both the Nunatak and Lobate Phases, again like closely spaced rings on an irregularly shaped “Bath Tub”. These are numerous, spanning a broad elevation range, suggestive of progressive, incremental, more or less steady lowering of the ice sheet. However, features are more numerous and larger at particular levels, which can be correlated across the State (using elevations adjusted for isostatic rebound) which supports the usage of a Bath Tub Model as a basis for deciphering deglacial history “stillstands.” 6As discussed elsewhere below, whereas “stillstands” are commonly regarded as indicative of climatic variations, that is not necessarily the case and not the intended meaning of the usage of this term here. Ice margin and drainage features provide links between basins, further documenting the correlation of ice margins at different, multiple levels across the State with different ice margin Styles, again supporting the applicability of the Bath Tub Model. The history of deglaciation as documented by ice margin features and presented in this report in the context of the Bath Tub Model is not just consistent with this physiography, but physiography as portrayed on such maps as above is suggestive of considerable detail as has actually been found.

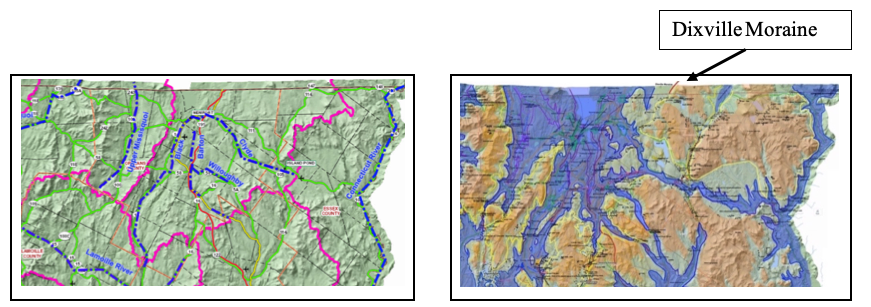

By way of underscoring and illustrating the close correspondence between Vermont’s deglacial history and its physiography, the map on the left below, taken from VCGI, shows drainage basin boundaries in northern Vermont in the Memphremagog Basin and portions of the adjoining Connecticut Basin, highlighted by purple lines, with individual surface water drainage systems by blue colored lines, all as exist today, in modern times. And the map on the right, also from VCGI ice margin mapping, shows the ice sheet extent in the Memphremagog Basin at a particular (“T4”) time with ice coverage shown by blue color shading, with discrete finger-like lobes extending across divides into the Connecticut Basin. The ochre shaded areas represent terrain above 1600 feet(488 m).

The ice margins of this blue shaded ice sheet are marked and documented by many stagnant ice deposits at correlative elevations, with elevations adjusted to take into account isostatic rebound effects. This ice margin represents the lower portion of the aforementioned T4 “hybrid margin,” which again is marked by stagnant ice deposits in contrast to the upper portion of the hybrid margin marked by Ice Marginal Channels associated with active ice. This hybrid ice margin is also part of the aforementioned ice margin “Signature,” which as discussed in more detail below facilitates mapping and correlation by easily recognizable, recurrent patterns. This T4 active ice margin receded northward to a new, lower T5 position while the stagnant ice deposits were still forming at the T4 level, as part of the “Everything, Everywhere, All at Once, and Continuing” Style.

The upper, active ice margin portion of the hybrid margin on the map above is marked by T4 Ice Marginal Channels which can be traced across the Memphremagog Basin where they correlate with the Dixville moraine in Quebec, as indicated by the small red line on the above map, right. Also, the T3 and T4 margin is correlated with the White Mountain Moraine System in the Littleton and Bethlehem area of New Hampshire (not shown on the above maps), as reported by Thompson et al, and as discussed at length below in Section 3. This correlation suggests that the blue shaded areas on the above map represents the ice sheet associated with an Older Dryas readvance, again as reported by Thompson et al, also as discussed below. Not shown on the above T4 map is the margin of the ice mass in the Connecticut Basin, marking the last of three Disconnections, as marked by Scabby Terrain at the late T4 level.

As reported by Thompson et al, the White Mountain Morainic System represents a readvance. It is believed that the T3 and T4 margins on the above maps in Vermont represent this readvance, again, marked by a “Signature” ice margin pattern which can be traced southward and westward across nearly the entire State of Vermont, with suggested correlations in New York, again as discussed in Section 3 below. This is also discussed in Appendix 3.

Of course, the close correspondence between physiography and ice margins results from using the Bath Tub Model and thus should not be surprising, and in a sense this observation entails circular reasoning. However, the fact is, and this is an important and key point, that in each and all of the Memphremagog basins, specifically the Clyde, Willoughby, Barton, Black, and Upper Missisquoi, very substantial (frontal ice margin) stagnant ice deposits occur at the same adjusted elevations at valley heads, extending across divides with neighboring Lamoille and Connecticut Basins in close contact with similar deposits at comparable elevations. This represents and reflects the ice margin being closely controlled by physiography in the “Bath Tub Model.”

Whereas the above maps give a general sense of physiography bearing on deglacial history, local and more detailed physiographic difference were important and are not so obvious by a casual examination of these large scale maps. For example:

- In the northern Champlain Basin, in the vicinity of the “Shattuck Mountain Pothole Tract,” which is discussed below, the foothills just north of the Lamoille Basin, extend further westward than much of the foothill front further north. This physiographic projection served to trap meltwater drainage from a large watershed area on the surface and along the margin of the ice sheet, which is presumed to have sloped southeastward, accounting for accumulation of substantial meltwater at this location, resulting in the development of many Bedrock Grooves, and the very unusual pothole tract.

- The micro-physiography of the floor of the Champlain Basin was important in regard to the development of a calving ice margin. The makers of physiographic maps generally rely on topography such as provided by USGS topographic contour maps. While this is appropriate for most general purposes, the omission of bathymetric information for Lake Champlain results in an incomplete and in a sense misleading picture of the physiography of the lowermost floor of the Basin. As discussed in more detail below, the floor of the Champlain Basin is not flat. Calving likely began at a relatively early time in the deepest western portion, south of the Champlain Islands(North Hero, Isle La Motte, Grand Isle, and South Hero), followed by calving at a slightly higher physiographic bench on the Basin floor in the Middlebury to Shelburne area.

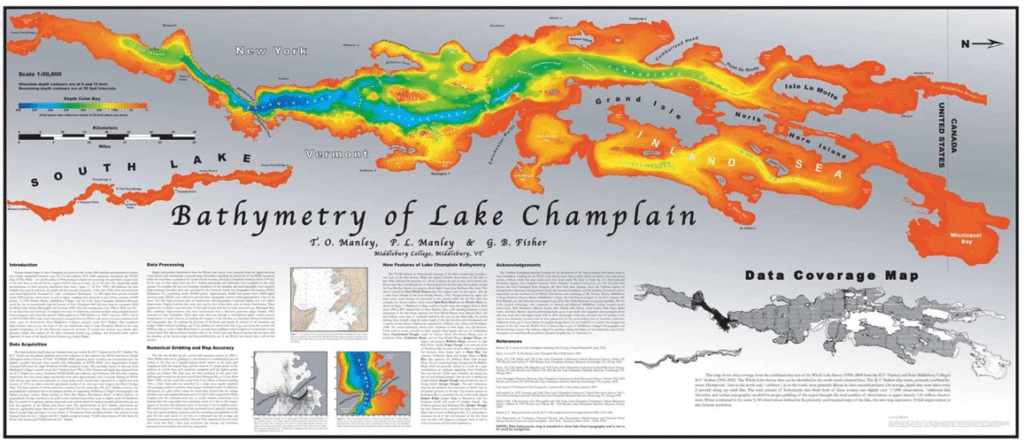

For example the following map 7This map is from an online source, with credit to Manley, T.O., Manley, P.L., and Fisher, G.B. at Middlebury College. shows the bathymetry of Lake Champlain:

This map is quite significant in that it shows the “Deep Lake” (the area of blue shading) as Vermont residents call the deeper portions of Lake Champlain, reaching depths of about 400 feet. Given that the elevation of present day Lake Champlain is about 100 feet above sea level, the bottom of the “Deep Lake” is well below present day sea level. Of course, this bathymetry was different in late glacial times owing to isostatic uplift since then. However, even taking this into account, the configuration of the Deep Lake portion of the basin is significant. It is here believed that the floor of the Lake Champlain Basin as depicted above represents an “overdeepened” basin. Overdeepened lakes are also found in the Memphremagog Basin, which likewise is not evident on topographic or physiographic maps. The term “overdeepened” is used here in the same context as the Finger Lakes of New York, where the Valley Heads moraines are remarkably similar to the Memphremagog Basin deglacial record. It appears that overdeepening relates to the narrowing of the physiographic “funnel” through which ice flow is constrained.

Footnotes: