The following is my open letter, in its entirety. This Open Letter was the start of my return to the Vermont Pleistocene after a hiatus of about 50 years.

In 1972 I summarized my previous six year’s research on the Pleistocene geology of northwestern Vermont, primarily in the Champlain Valley, from approximately Middlebury to the Canadian border. 1 (Wagner. P 1972 ICE MARGINS AND WATER LEVELS IN, NORTHWESTERN VERMONT, Guidebook for field trips in Vermont: New England Intercollegiate Field Conference 64th annual meeting October 13, 14, 15, 1972 Burlington, Vermont: Trip G-2[1], pp 317 – 358). At the time, my research was aimed at understanding the glacial features associated with the waning Laurentide ice sheet. However, as it turned out, deposits or other features marking the northward retreating ice sheet margin in this area are rare. My report necessarily became primarily a history of late glacial lake(Lake Vermont) and marine(Champlain Sea) water levels in the Champlain Valley and adjacent upland areas of VT. It documented in greater detail but basically confirmed previously published findings by Chapman, 2 Chapman, D. H., 1937, Late-glacial and post glacial history of the Champlain Valley: Amer. Jour. Sci., v. 34, p. 89-124. and added information about local proglacial lakes in upland tributary valleys.

Chapman delineated proglacial Lake Vermont, including Coveville and Fort Ann Stages, and multiple levels of the Champlain Sea, all related to the progressive retreat of the Laurentide ice sheet margin. 3 The position of the northward retreating ice sheet margin in the Champlain Valley can be located relative to these water bodies by information about local lakes in tributary valleys. For example, multiple local lakes in the Winooski Valley generally drained into the main Champlain Valley regional water bodies at the lowest available topographic divides with drainage thence into the main Champlain Valley with delta formation at the regional lake level. This information implies that the sheet margin was at that time still blocking the lower Winooski so as to cause the ice dam, but at that time was north of the delta. The problem is that Coveville and Fort Ann stages lasted a long time, during much of the deglacial history of Vermont. Fixing the ice position by correlation with local lakes is interesting but does not provide useful information for understanding the regional history, for example in relation to ice margins across the Valley in New York or to the north in Quebec.. My report hinted at an ice margin in late Fort Ann and early Champlain Seas time, and suggested a possibly more complicated history of events in the northernmost portion of the study area, mostly in the Mississquoi Valley area, in two respects

- Champlain Sea deltaic deposits were identified with overlying veneers of deeper water, fine grained sediment cover, and in one case with included bodies of glacial till. This evidence suggests that the ice sheet had first retreated sufficiently to allow marine water into the Valley, followed by a readvance which again impounded higher water levels.

- Strandline features were identified at multiple locations in the Champlain Valley which suggested an additional water plane below Fort Ann and above Champlain Sea level, possibly related to an outlet channel(?) near Greens Corners. It was suggested that the raised water level might have been related to and caused by the readvance.

Unfortunately, in the early 1970s in northern Vermont, including the Mississquoi Valley, only small scale topographic maps(1:62,500 were available, which made detailed study difficult. As a consequence I was only able to examine the Mississquoi Valley at a reconnaissance level. Since then, more detailed maps and new technologies, such as Lidar, have appeared. And as well, ongoing research in the past 50 years by others has resulted in significant advances in the understanding of Pleistocene geology in northern New England, New York, and Quebec.

Recently, in my brief cursory reading of some of the newer literature I was especially struck by reports on research in Quebec, generally south of the St Lawrence River, on the flanks of the Appalachian uplands. These findings tell the story of late glacial history in a broad conceptual framework that for the first time, in my opinion and delight, establishes a model for a better understanding of regional Quaternary features and events. It now seems clear that the Laurentide ice sheet retreat in the St Lawrence lowland generally took place by a progressively shrinking, northward retreat of the ice margin, down a regional topographic slope at the northern end of the Appalachian uplands Valley, and marked by an array of multiple recessional end moraines, and accompanying pro-glacial fresh and salt water bodies and associated features,. Such moraines have been identified in various locations in Quebec, which at their southwestern-most extent are quite close to the Mississquoi Valley.

It appears to me that the Mississquoi Valley likely represents a link between documented glacial and water body events in both the Champlain Valley and St Lawrence lowland, and possibly to the west in New York and possibly even Ontario. To my knowledge, little if any new work has been done in the Mississquoi Valley. Left unresolved is the specific position of the ice sheet margin relative to regional water bodies and features elsewhere in the region.

My 1972 report documents the northward retreating ice sheet margin in the Champlain Valley relative to local proglacial lakes in the Winooski and Lamoile Valleys at Lake Fort Ann time. Based on more recent research the Fort Ann stage of Lake Vermont apparently extended northward into the St Lawrence Valley, implying that by later Fort Ann time the ice sheet margin had retreated sufficiently northward to allow Fort Ann waters to extend over a broad area, including into both northern New York and Canada. Subsequently, the corridor between the two lowlands was opened so as to allow complete invasion by the Champlain Sea. But as yet the correlation of ice margin features in the Champlain Valley including the Mississquoi Valley with reported features in Quebec and New York remains uncertain.

I have not, nor do I intend to revisit this story in any serious way. However, some of the recent literature and more detailed maps have caused me to ponder about parts of this story that I recollect from back in 1972, especially for the Mississquoi Valley. This has prompted me to take a fresh look at some of my old data, with the benefit of new information from the literature and as well improved base map and associated related data. This “open letter” offers recollections, reflections, and new insights, which I hope will encourage others to take a fresh look.

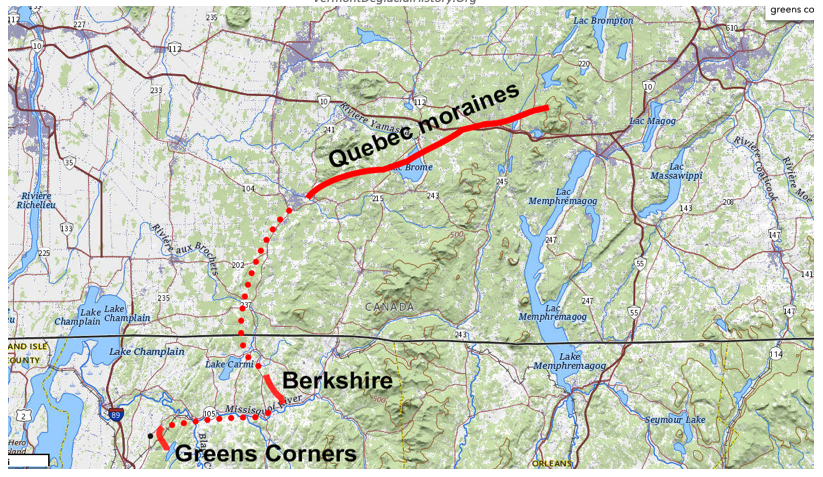

The map below depicts the regional topography and drainage of the Mississquoi Valley and southern Quebec. This base map was taken from online USGS internet open source data. 4 topo https://topobuilder.nationalmap.gov/ Also shown(dashed gray line line) is the approximate location of Laurentide ice sheet moraines, as indicated on Figure 6 of a report by Parent and Occhietti, 5 Michel Parent et Serge Occhietti, 1988, Late Wisconsinan Deglaciation and Champlain Sea Invasion in the St. Lawrence Valley, Québec, Géographie physique et Quaternaire, vol. 42, n° 3, 1988, p. 215-246. Their position is only approximately drawn by me, the purpose being to show the regional setting and close proximity to the Mississiquoi Valley and what I believe are correlative ice margin features.

In Vermont, in particular in the Mississquoi area, so far as is known to me, no linear moraines comparable to those found in Quebec have been identified. Of course, as already noted, the Mississquoi area has not been studied in detail. However, with the benefit of more detailed topographic and other information, and a one day field trip to check and verify suspected features, I have developed new insights about the ice sheet margin and associated water levels.

Ice margin evidence in the Mississquoi region exists near Berkshire and Greens Corners, as marked on the above map. It seems reasonable to me that these three locations together demarcate an ice margin. However, the research in Quebec includes multiple ice marginal positions. I believe the features in the Mississquoi Valley, while broadly correlative, likewise were deposited progressively over a relatively short span of time. Thus, the demarcation on the above map is believed to represent the ice margin in that context.

It is important to note that, as reported by others, the ice front positions in Quebec were closely controlled by regional topography. In general, the waning ice sheet was able to fill lowland areas below about 600 – 800 feet, more or less, but its further advance apparently was hindered by higher elevation land masses of the Appalachians to the south. And of course, along much of its margin the ice sheet was fronted by fresh and salt water bodies, which likely served as an additional impediment.

The same applies as well in the Mississquoi. The Berkshire features are at the base of the same upland as the western most portions of reported moraines in Quebec, so to speak, being “just around the corner from each other.” The Greens Corners features are on the southside of the Mississquoi Valley, actually on flank of uplands which lie just at the “corner” between the Champlain Valley and the Mississquoi Valley. Thus, I believe together these are links, remnants of an ice margin, which is not continuously marked, but with gaps which I presume are related to intervening areas where proglacial water bodies likely resulted in an unfavorable environment for depositional features.

In the following, I briefly summarize my understanding of features and events related to the late glacial and associated proglacial history in the Mississquoi Valley pertaining to the ice marginal features described above.

Berkshire ice margin feature

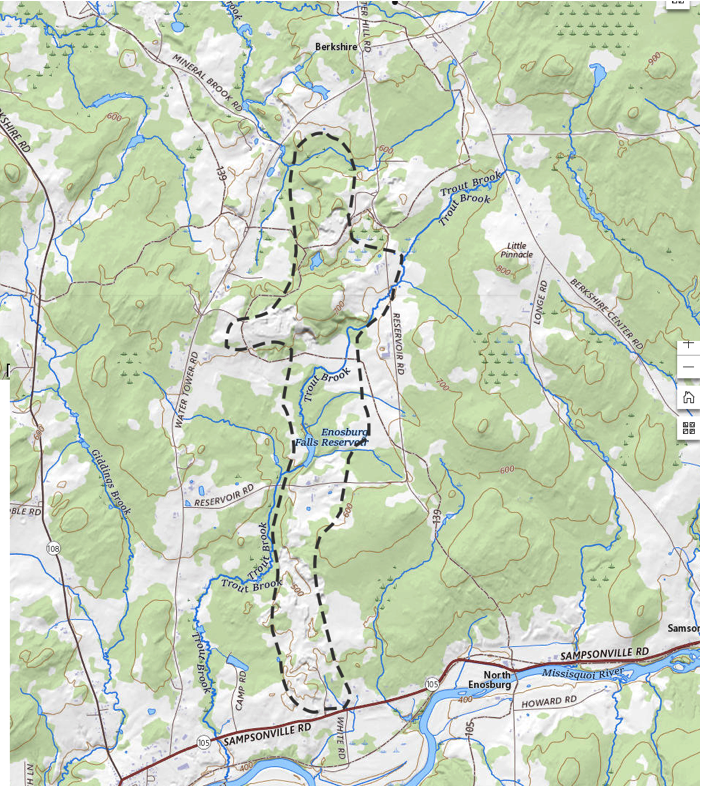

Just south of the village of Berkshire. This is a small, apparently isolated area of classic kame and kettle stagnant ice type of ice marginal feature, as can be seen by its topographic expression on the following map: 6 This map was taken from a USGS online source: https://topobuilder.nationalmap.gov/

A gravel pit at the southern tip of this feature was examined for the 1972 report, showing sand and gravel with typical stagnant ice structures, intermixed with masses of lacustrine or marine silts and clays. However, at that time the extent of the deposit was unknown by me. Newer information, however, documents its extent. The Vermont Center for Geographic Information publishes online Lidar shaded topographic information, 7https://maps.vermont.gov/vcgi/html5viewer/?viewer=vtmapviewer with optional overlays for a large variety of different types of mappable features. One such feature is for soils with varying suitability for onsite sewage disposal, which gives information pertaining to areas of more permeable soils, typically sand and gravel. This shows such soils corresponding with the of hummocky topography Near Berkshire, the deposit takes on a broad east-west arcuate ridge-like form, perhaps roughly about a mile in length, approximately ½ mile wide, with crest elevations at about 700 feet. However, southward the deposit is in the form of a ridge oriented north-south, at a crest elevation of roughly 500 feet, extending from the vicinity of Burleson Pond southward, ending near the Mississquoi River at Route 105 at Enosburg Falls. I field checked the deposit in September 2023, which verified its identification. Gravel pits indicate its thickness is locally in excess of 75 feet. Whether or not the deposit ridges were formed parallel to the ice margin as a typical recessional end moraine, or at some angle to the margin as an esker, or some combination of these, are unknown.

Notes from my field work in the 1970s at a gravel pit along Route 105 at the southern terminus of the ridge(the ridge probably originally extended further south but was cut by river erosion and construction of Route 105) indicate typical stagnant ice sand and gravel, but significantly, also intermixed masses of fine grained lacustrine or marine sediment.

In essence, the Berkshire deposit represents an ice margin feature, some form of a recessional moraine type deposit. The lower ridge crest elevation at about 500 feet is quite close to or at the elevation of the Champlain Sea in the Mississquoi(Wagner, 1972). My 1970s notes from nearby exposures both to the immediate east and west of the Route 105 gravel pit, and as well on the immediate south side of the River, south of Enosburg falls, indicate till masses intermixed with or overlying fine grained lacustrine or marine materials. Based on the lower elevation and position of the Berkshire feature it seems likely that this feature was deposited in Champlain Sea time.

To complicate matters, my 1972 finding that Champlain Sea delta deposits in the Mississquoi Valley are veneered with fine grained, deeper water sediment, and in one case interbedded with glacial till suggests that the Berkshire feature may have involved a a readvance of the ice sheet margin.

The delineation of the inferred ice margin in the Mississquoi Valley as shown on the regional map suggested the ice sheet closely conformed with regional topography, with a lobe advancing eastward, up the Mississquou valley. In general, the terrain on the south side of the Mississquoi Valley rises significantly to higher elevations, which likely would have prevented the extension of the ice sheet in that direction, except possibly in several tributary valleys. A limited survey of the area on the south side of the Valley did not reveal any indication of an extension of the ice into this area.

Greens Corners

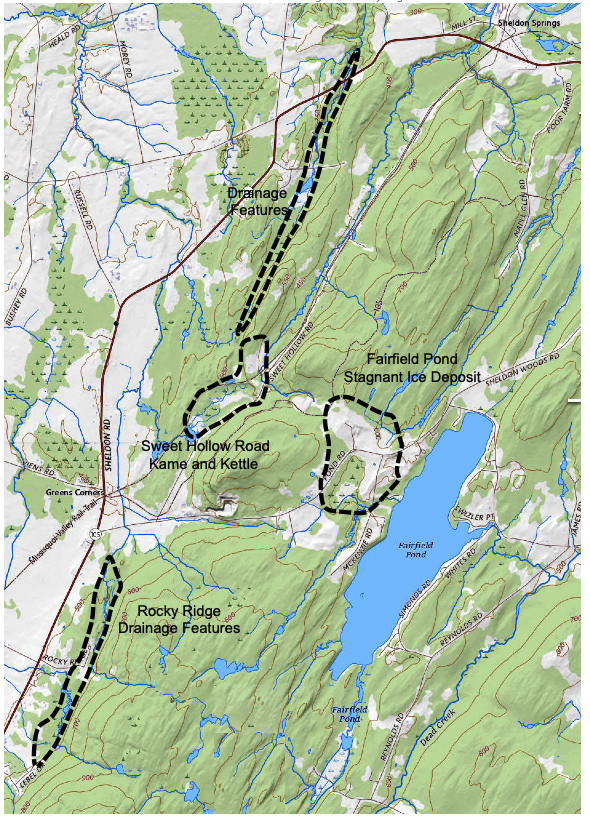

The second area with evidence of an ice front is in the vicinity of Greens Corners, as marked on the above regional map. The map below shows the locations of features described in the following.

Greens Corners is a small Vermont community with a handful of houses, a few miles northwest of the city of Saint Albans. The Saint Albans area is within the Champlain lowlands proper, generally below an elevation of about 600 feet. To the east of the City the terrain rises sharply – rampart-like to a substantial bedrock upland area with elevations over 1000 feet. Greens Corners lies on the lower, northwester flank of that upland, essentially at the corner between the Clamplain Valley lowland and the Mississquoi Valley.

I believe multiple features in the Greens Corners area were formed at an ice margin. The features are roughly at comparable elevations as the Berkshire deposits and likely therefore are roughly correlative in time. However, some of the Greens Corners features may have developed sequentially, beginning earlier with the highest feature to the southeast, and continuing toward the northwest at progressively lower elevations. The available information is insufficient to establish such differences. The following is a brief description of these features, proceeding from generally higher and therefore possibly older, to lower and possibly younger. To facilitate discussion, these features are located on the following map, which is again based on the same online USGS map source as above, each identified with reference to prominent names in their locale.

Fairfield Pond Stagnant Ice Deposit

This deposit is located in an upland area immediately west of Fairfield Pond. It consists of strong hummocky, typically kamic topography. Outcroppings indicate gravelly soils. The feature generally occurs at an elevations ranging from about 580 feet – 620 feet. The deposit makes up the topography on the west side of Fairfield Pond, but only thin ground moraine with numerous bedrock outcroppings have been found along the east side of the Pond. The elevation and depth of Fairfield Pond are about 548 feet, and 40 feet respectively. Bedrock outcroppings occur near the Pond outlet, indicating that the Pond is in a closed basin, likely a kettle hole with a block of ice at the time of stagnant ice feature formation.

It is believed that the stagnant ice deposit was formed by a lobe of the main ice sheet in the Champlain Valley immediately to the west. The area immediately west of the deposit generally is a bedrock ridge with elevations of 700 – 800 feet and above. However, a low topographic divide on that ridge presently has an elevation of 660 – 680. The stagnant ice deposit extends across this divide. The thickness of the deposit at this divide is unknown, but judging from the topography could be several tens of feet. An alternative connection with the ice sheet that formed this deposit hypothetically could have been a lobe of ice extending from the Mississquoi Valley southward up the drainageway of Black Creek. However, a reconnaissance of that area showed only thin, patchy ground moraine over shallow bedrock.

Rocky Ridge Drainage Feature

Just southeast of Greens Corners are two topographic linear drainage elements, in both cases marked by surface water drainage lines extending down the west side of the bedrock hill, just west of Fairfield Pond. The drainage lines are abruptly and strongly diverted, into linear drainage swales. The elevations of the bottoms of the drainage swales vary but are on the order of 550 +/- feet. Both swales are bounded on the east by a bedrock hillside, and on the west by pronounced ridges which are mostly bedrock but in places by gravel deposits generally with no distinctive topographic expression ridges but in places faintly kamic.

Care is required in inferring these swales to have formed at an ice margin, given that in much of Vermont the underlying bedrock commonly imparts a grain to the topography. In this case, in fact, the swales are oriented roughly parallel to the bedrock structural grain. However, the swales are unusually pronounced and the drainage patterns exceptionally diverted. The “clincher” is that the swales are bounded by ridges on their western flank which although predominantly bedrock locally include gravel deposits, in one location with kamic topographic expression. I believe the channels were cut along the margin of the main ice sheet in the Champlain Valley.

Sweet Hollow Road Kame and Kettle and Drainage Feature

East of Green Corners is a ridge like deposit of sand and gravel that lies athwart and at the head of an unnamed, long, narrow, and pronounced surface water drainage channel, extending to the northeast. Remnants of two old gravel pits in this deposit are evident, but are too overgrown to discern any geologic information. According to the property owner both gravel pits were active more than 50 years ago. The deposit has a flat top surface, which slopes north-northeastward, down the valley in which Sweet Hollow Road is located. The elevation of the top of the ridge is at about 500 feet. To the south is a mostly enclosed, oval-shaped topographic basin, the floor of which is at an elevation of about 460 feet. The same property owner indicates that the basin is a natural feature fundamentally unaltered by gravel excavation. In my opinion the basin is likely a kettle and the ridge a kame or kame terrace. This feature is located at the head of a relatively narrow, deep, and elongated drainage channel, roughly parallel to the above described channels, and likewise is suggestive of ice marginal drainage.

The drainage channel to the northeast of these features which was considered in my 1972 report as related to control of “Lake Greens Corners,” a previously unreported strandline between Fort Ann and Champlain Sea levels. In essence, I inferred a spillway at the head of this channel. I now believe that this is incorrect, in as much as the gravel deposit at the head of the channel could not have sustained major drainage without being substantially eroded. And in fact no actual spillway outlet exists. However, I continue to believe that this channel was related to the lowering of Lake Fort Ann to a lower level which would correspond to a strandline at the Lake Greens Corners level, because otherwise the level of a higher level could not be sustained. The absence of an actual spillway I believe is explained by this location being at an ice margin, with blocks of ice preventing the formation of a spillway. Toward the northeast, down this drainage way, is evidence of multiple fluvial surfaces. An upper terrace may be graded from the ice contact deposit at the head of the spillway, downstream to deltaic deposits in the Mississquoi Valley associated with Champlain Sea levels at about 320 feet, below the marine limit. This would suggest that the ice may have stood at the location of this feature in later Champlain Sea time. At this point more detailed study of this drainageway is needed.

Other conspicuous drainage channels

Finally, northwest of the features and drainage just described at Sweet Hollow Road is another area of conspicuously linear drainage features. These likewise are unusually pronounced erosional topographic swales, apparently predominantly in bedrock. The elevations of swale troughs is lower than the similar features south described above, and likewise may be graded to deltaic deposits which are at elevation of about 350 feet, corresponding to lower Champlain Sea stages in my 1972 report. In my opinion, the channels are likely to be ice marginal features, particularly given the context of their proximity to other similar features as described above. However, insufficient detailed information exists to definitively link the drainage to standing water levels in the Mississquoi basin.

Ice sheet and Associated Water Body History

The question remains as to the history of ice sheet and associated water body events in the Mississquoi Valley associated with the ice margin features just described and depicted on the above maps. Answering this is a matter of testing alternative hypotheses against all of the available information. I suggest that the available information suggests that the most likely scenario is that prior to the deposition of the moraine in the Mississquoi Valley the ice sheet had retreated to drain the valley of any local lakes(as are typical throughout the region) and for Fort Ann Lake Vermont to enter, resulting in Fort Ann deltas in the Valley. Fort Ann features have also been identified in Quebec, indicating that Lake Fort Ann waters extended across a broad region at the ice front.(Interestingly, no Fort Ann features have as yet been identified in the area immediately beneath the footprint of the inferred ice mass in the Mississquoi valley.)

Next, further retreat of the ice sheet in Quebec allowed for the draining of Lake Fort Ann and the invasion of the Champlain Sea, including into the Mississquoi and Champlain Valley. Again, this phase is marked by marine limit deltas throughout the Champlain Valley and the Mississquoi.

The information given here suggests that the ice sheet then readvanced, sufficiently to again block drainage in the Mississquoi Valley(and likely as well the Champlain Valley to the south), to establish the Berkshire, Fairfield Pond, and Greens Corners features. That this readvance took place in Champlain Sea time is suggested by the presence of fine grained sediment veneers on deltas in the Valley, and in one location by an interbedded mass of till.

The elevation of the raised water levels in both the Champlain and Mississquoi Valleys at this time are uncertain. In the Champlain Valley, the Fort Ann level may have been re-established, or perhaps this is when my(Wagner, 1972) suggested Greens Corners stage was established. If in fact either of these water levels was established, the elevation of the water planes at roughly 700 and 650 feet(check this) would have been sufficient to extend into the Mississquoi drainage basin. For example, topographic divides between Greens Corners and Fairfield Pond are about 600 feet. In fact, the sand and gravel deposit extending easterly, downward from the topographic divide between Greens Corners and Fairfield Pond, toward the Pond is a case in Point. It could be argued that in fact the features in the immediate Fairfield Pond vicinity are themselves indication of a shoreline. Alternatively, a local water body In the Mississquoi could have been established. At this point, the former case is favored.

Further in regard to the water levels of proglacial water bodies at the time of the maximum readvance, the close correspondence of both the Berkshire and Greens Corners ice marginal features, at roughly 600 feet, generally along the lower slopes of higher uplands, likely was not a coincidence. It can be hypothesized that in fact the ice sheets advance was limited by the combination of topography and one or more proglacial water bodies. In a sense, its readvance was not only regionally uphill, but as well in the face of standing water, first the Champlain Sea and then by the Fort Ann Stage(and/or Greens Corners) of Lake Vermont. The buoyant effect of an ice mass confronting a water body is well known to be an important glaciological physics force.

Evidence in support of such events, specifically, the opening of the Mississquoi to allow for the Fort Ann and Champlain Sea incursion, followed by a readvance of the ice to the ice marginal locations described above, and then finally recession of the ice front to once again allow for Champlain Sea incursion, includes:

- Fort Ann deltas in the Mississquoi Valley. These were not idebtified in my 1972 report, but based on new topographic maps appear to exist(again, excepting perhaps beneath the footprint of the readvance).

- Champlain Sea deltas in the Mississquoi Valley with fine grained sediment veneers, and in one instance with intermixed till.

- The fact that the lower end of the esker(?) south of Berkshire is at 500 feet, corresponding with the elevation of the Champlain Sea, and that an exposure at this location shows ice contact fluvial gravel intermixed with fine grained and now presumed to be marine sediments.

- Multiple other exposures near Enosburg Falls showing till intermixed fine grained silt-clay materials.

- The preponderance of fresh ground moraine on the terrain west of the Berkshire moraine.

- The close correspondence of multiple ice margin features as described above, all at or close to an elevation of 600 feet, and all at a similar topographic positions at the lower flanks of substantial bedrock uplands.

It may be that the duration of this re-blockage was brief, as suggested by the fact that Champlain Sea deltas in much of the Champlain Valley to the south do not have fine grained veneers, unlike the case of the Mississquoi. Perhaps this is explained by the latter’s’ proximity to the ice margin as a sediment source.

Finally, the fact(?) that some of the drainage features at Greens Corners are graded to deltas associated with lower Champlain Sea water levels, suggests that this readvance may have taken place near the end of Champlain Sea maximum marine limit time, lasting long enough so that its retreat occurred in later Champlain Sea time.

In my 1972 report I suggested that a local Champlain Valley inundation was caused by the readvance of the ice margin, resulting in Lake Greens Corners. This remains a plausible hypothesis. But what was the nature of Greens Corners linear elements as drainage control mechanism for waters ponded by the ice sheet in the Champlain Valley at this time, either Fort Ann or Greens Corners? My 1972 report suggests that drainage at Greens Corners was down the outlet channel, with the channel floor graded into presumed deltaic deposit at the marine limit. With the benefit of newer, better topographic information, this apparently needs to be revised to correlate Greens Corner drainage with a Champlain Sea feature below the marine limit, as described above. But also as noted, the head of the Greens Corners drainage way is a kamic deposit, not a classic spillway outlet channel. Moreover, whereas the erosional features along the drainage way suggest substantial water flows, more than might be expected by the small stream now present in the drainage way, if this channel accommodated the entire Champlain Valley Lake Fort Ann and/or Greens Corners drainage, the strength of the erosional “signal” in the drainageway would seem quite underwhelming.

The kame and kettle at the head of the Greens Corners drainage channel is at an elevation of about 500 feet. In contrast the tongue like deposits on the hill side west of Fairfield Pond have a maximum elevation of about 600 feet. And northwesternmost channels are graded to levels close to 300 feet. These observations suggest that the elevation of the ice sheet was slightly above 600 feet in the Greens Corners vicinity when the linear draninage ways and the Fairfield Pond deposit formed. It is not so far-fetched to imagine that drainage took place at Greens Corners through crevasses in the ice, beginning the lowering of Lake Fort Ann and/or Lake Greens Corners in the main Champlain Valley to Champlain Sea in the Mississquoi Valley, possibly marked by a relatively brief pause at Greens Corners strand line. Only slight ice retreat would have continued, with both ice sheet surface and receiving water lowering, causing scour channels at or close to the ice margin as reported here. In any case, the drainage at Greens Corners strand likely was not via a typical open channel outlet channel.

A closer examination of elevations of the ice marginal features at both the Greens Corners and Berkshire areas shows that the elevations are not exactly the same. The Berkshire deposit ranges from about 800 feet near Burleson Pond to about 500 feet at its southern limit. The Greens Corners features range in elevation from about 660 – 680 feet(the northern most divide between Greens Corners and Fairfield Pond), 580 feet( the divide in the same area along Pond Road), about 660 -680 feet for the southernmost hillside channel, 520 – 540 for its neighbor to the north, 500 feet at the head of the Greens Corners sluiceway, possibly graded downward to a Champlain Sea delta at about 320 feet, and 480 – 320 feet for the neighboring drainageway to the west. These differences suggest that these features are broadly synchronous in age but more likely span a range of time, with the readvance initially taking place into the Champlain Sea while at its marine limit, to its maximum advance when the ice margin was fronted by Fort Ann and/or Greens Corners waters to a slightly later time, during which the ice margin was receding and again fronted by the Champlain Sea, now at a later stage.

The Fort Ann, Greens Corners, and Champlain Sea maximum strand lines in this area, as described by me in my 1972 report(Figure 3 are at about 700, 650 and 500 feet, respectively. This suggests that an ice front at Greens Corners likely was fronted by standing water to its south of the Fort Ann or Greens Corners stage at an elevation of 650- 700 feet. A readvance into Champlain Sea waters, initially at an elevation of about 500 feet per my suggestion that this occurred so as to once again exclude marine waters from the Mississquoi Valley, suggests substantial hydraulic head differences. Of course it is likely that a local, higher level water body was impounded by the ice at this time. Nevertheless. the elevation difference between Fort Ann waters at 700 feet(or 650 feet for the Greens Corners strandline) and 500 foot level in the Mississquoi Valley, as would have been the case as the ice re-entered the Mississquoi would likely have resulted in enormous, tremendously powerful drainage, perhaps capable of causing substantial subglacial scour, and as well substantial esker development. It would seem that the retreating, re-advancing, then stabilizing, and finally once again retreating ice front in the thalweg of the Mississquoi Valley must have been an awesome, dynamic place at that time, marked by calving induced by both flotational forces and as well confined hydraulic forces within a typical ice marginal crevasse environment. This would hardly be a locale where one would expect moraine deposition. But at the ice margin’s “grounding points,” it would be reasonable to envision tremendous subglacial scouring action on the south side of the calving front, such as at Greens Corners, versus a calmer environment on its north side, such as the Berkshire moraine. It would seem that the glacial geology features of the Mississquoi Valley in this respect offer not just an opportunity to fill in the gap of the chronologic history, including the connection between the Champlain and the St Lawrence Valleys, but to examine and better understand the nature of an enormous ice sheet margin receding downward from a regional upland terrain, fronted by similarly enormous drainage.

Footnotes: