Having described the ice margin features mapped on VCGI, we now turn to the usage and interpretation of these features in the “Bath Tub Model,”” in essence speaking to 1) the validity and usefulness of the “Model” and 2) the mechanics of its usage, per the following.

- Validity and usefulness of the Model

As previously indicated, many authors of research reports, including in nearby areas of New York, Quebec, and New Hampshire, have observed a correspondence between ice margins and physiography, related to the thinning of the ice sheet. For example:

- In Quebec, Parent et Occhietti, as already noted, suggest that moraines can be correlated on the basis of their elevation, orientation, and alignment, which was the inspiration for the “Bath Tub Model.” The T4 margin in Vermont is correlated with the Dixville moraine, which is one of the older moraines in Quebec, and the T8 margin with the Sutton moraine. Thus, most of the deglacial history in Vermont is correlated with the Quebec moraines.

- De Simone and La Fleur,1 De Simone, D.J. and La Fleur, R.G., 1985, Glacial geology and history of the northern Hudson Basin, New York and Vermont; NYGSA, pp 82-84. who mapped ice margin positions in the northern Hudson Basin and the western Taconics, including parts of southwestern Vermont, specifically refer to the thinning of the ice sheet and topographic control of ice margins, which is evident in their map of recessional ice margins. The T3 and T4 ice margins identified on VCGI in Vermont using the Bath Tub Model correlate with their positions 1 and 12. Similarly, ice margin maps by Franzi and colleagues for northeastern New York (personal communication: Franzi, 2024 and 2025), much of which corresponds with the western side of the Champlain lobe at a late time in Laurentide deglacial history and was the dominant ice lobe in Vermont, likely show at least a rough general correspondence between ice margins and physiography.

- Thompson et al 2 Thompson, W.B., et al 2017, Deglaciation and late-glacial climate change in the White Mountains, New Hampshire, USA, Quaternary Research, V 87, pp 96-120. identify multiple moraines in the Bethlehem-Littleton New Hampshire area which show a correspondence with elevation, likewise correlated here T3 –T4 times , which again is a relatively a relatively early time in the Vermont chronology.

Thus, these observations suggest that much of the Vermont deglacial history being studied here was late in the in Laurentide ice sheet glacial history when thinning of the ice sheet was sufficient to establish at least a general conformance of the ice margins to physiography.

At the beginning of this study it was assumed that the Model can be used, with care, as a basis for establishing deglacial history of Vermont. As noted above, the basis for this assumption came from reports which suggested that moraines in Quebec can be correlated by their elevation, orientation, and alignment, in essence, the “Bath Tub Model.” As noted above, obviously, the physiography of southern Quebec tends to be gently sloping, rather flat sloping terrain. However, near the Vermont border in the Piedmont of Quebec, the terrain is irregular, not unlike large portions of Vermont.

The following sidebar is offered in support of the usage of the Bath Tub Model and its validity for deciphering deglacial history:

- I first started my mapping project in the Memphremagog Basin. By luck it turned out that this was a helpful place to start for several reasons related to testing and establishing the usefulness and validity of the Bath Tub Model. Ice margin features are numerous and in close proximity, and found in neighboring smaller tributaries, at multiple correlative elevations, making it easy and obvious to identify, correlate, and map multiple ice margins across the Memphremagog Basin at correlative levels and times. In general, the same was found in other Vermont Basins, meaning that large gaps between data points are uncommon.

- As explained below, Ice Margin Channels and stagnant ice deposits are so numerous as to identify a Nunatak Phase and a subsequent Lobate Phase. “Ice Marginal Channels” are intriguing These are short sinuous grooves on hillsides, often occurring in flights at multiple levels. I take these as marking the emergence of nunataks, but in the Memphremagog Basin these features are so numerous as to be mappable and correlative, showing the lowering of the ice sheet in a Nunatak Phase, progressing into a Lobate Phase. This Nunatak to Lobate Phase history is identified across the State. I interpret these features as marking the margins of active ice, giving way to stagnant ice margins.

- This recurrent pattern was helpful in that together these features show the progressive development of lobes in relatively close conformance with the physiography in basins, sub-basins, sub-sub basins, etc. This same transition from a Nunatak Phase into a Lobate Phase was identified across the State, albeit with the transition occurring earlier in southern Vermont.

- Ice Marginal Channels provide strong links to the White Mountain Moraine System, which was studied by Thompson et al who identify a readvance. I gave a lot of thought to the nature and origin of Ice Marginal Channels, particularly in the context of the WMMS readvance. I concluded that at least some of these (at the T4 level and time) may mark the margins of polythermal ice where the basal ice had been warmed so as to allow confined meltwater drainage beneath the ice, but with the meltwater also dammed by cold basal ice in deeper portions of ice lobes, and by terrain irregularities such that the grooves mark locations where imponded, and again confined, subglacial meltwaters drained across terrain irregularities, much like outlet channel spillways for surface water lakes. My hypothesis is that the basal ice may have been warmed by the readvance over “warmed” terrain. The significance of such features, beyond an intriguing explanation for the formation of these Channels, is that I am able to identify and correlate certain such Ice Margin Channel and stagnant ice deposit combo hybrid margins across the State as a “Signature,” independent of elevation. Thus, for example, this Signature can be identified in the Bethlehem-Littleton area, the Upper Connecticut Basin more generally, the Memphremagog Basin, in the Winooski Basin where Larsen and Wright mapped “readvance” features, and in the Vermont Valley in southwestern Vermont.

- Further, Ice Marginal Channels in the Memphremagog Basin are interpreted as marking active ice margins which are closely associated with stagnant ice margins at similar but slightly lower stagnant ice deposits. This occurs at repeated levels, enabling me to map and identify “hybrid margins” with separate, discrete active and stagnant ice components. All of my T margins are hybrid types. It turns out that recession was so rapid that drainage from ice remaining in older, higher stagnant ice deposits extends downgradient to the next younger active ice margin, representing a “dance” between receding active and stagnant ice margins. This further helps to build a fairly detailed deglacial history, based not only on ice margin features at multiple elevations but as well drainage features. And of course, such drainage, especially for standing water bodies, is not dependent on ice sheet gradients with the inherent and attendant uncertainty.

- Certain specific stagnant ice deposits (at the T4 level and time) extend across divides with neighboring Connecticut and Lamoille Basins, establishing easily traceable links between Basins. Further, drainage patterns similarly provide links. For example, multiple drainage features related to the T4 ice margin in the Memphremagog Basin can easily be correlated with Lake Winooski strandline in the Lamoille and Winooski Basins, which in turn can be linked with Lake Winooski drainage into the Champlain Basin, to strandlines with Lake Vermont , which can then be linked to ice margins in southern Vermont. Thus, such links extend my correlation from the Quebec border southward into central Vermont and in turn linking to ice margins in southernmost Vermont.

- As the study progressed it was further observed, for example, that multiple ice margins in the northern Champlain Basin occur at the same elevations(when corrected for isostatic rebound) as ice marginal features in the Memphremagog Basin, despite the fact that these basins had very different environmental conditions.

- I would add one more piece to this sidebar. In the Champlain Basin, in the 1960s and 1970s I mapped features which back then I did not understand but I now have come to see as markers of calving ice margins. On the Vermont side of the basin these features are numerous and have led to my identifying five ice streams, each marked by unique features showing the progressive recession of grounding lines, from an early time with the ice margin far to the south, continuing northward to the Quebec border. I see calving beginning in Coveville time, mostly on the New York side of the basin, dramatically increasing at the lowering from Coveville to Fort Ann levels, and again from Fort Ann to Champlain Sea. I believe the substantial and rapid lowering of water levels served as a driver for ice lobe destabilization and calving. For example, I correlate my T7 ice margin to an ice margin identified by Franzi and others near Covey Hill, where the breakout is close to the transition from Coveville to Fort Ann which I see as the best, strongest link between VT and NY. Further, I see not only flattening of the south-facing frontal tip by calving, but also the development of a narrow “more or less open water “Disaggregated” ice margin corridor along the eastern margin of the Champlain lobe, which rapidly extended northward, resulting in destabilization of the eastern margin as a lateral margin , and its conversion into a frontal margin. Such proglacial water bodies and calving margins are part of the accelerated recessional history, which I see as a progressive collapse of the Champlain lobe beyond a tipping point. This helps to explain the fast ice margin recession and its short history in late deglacial time.

My point of the above sidebar is that whereas I started my mapping using elevation as a guide for ice margin features per se, this developed into a much more robust history story in conjunction with meltwater and standing water. Thus, the deglacial history presented here is not only based on ice margins with reference to ice sheet surface elevations in the “Bath Tub Model,” with their attendant ice sheet gradient problem, but in the final analysis has utilized more diverse evidence, making this deglacial history story more robust, defensible. and convincing.

VCGI mapping, showed that the later ice margins, when the ice sheet was relatively thin, showed a remarkable tendency to be affected or controlled by even minute physiographic differences. But the evidence indicates that even the older and higher ice margins tended to conform with the larger physiographic terrain elements. Thus, it is believed that by the time of the ice sheet recession in Vermont, the ice thicknesses were sufficiently diminished so that most Vermont ice margins can be correlated on the basis of the “Bath Tub Model.”

As previously stated, the application of Bath Tub Model was conditioned and qualified, by assuming that the thinning of the ice sheet in Vermont during deglaciation had small gradients equilibrated to physiography such that ice margin features formed perpendicular to ice sheet flow lines can be used as ice margin elevation markers for purposes of correlating or differentiating ice margins of the same or different ages. This qualification pertaining to flow line perpendicularity is important.3 Its importance is illustrated by the above discussion about Ice Tongue Grooves where it appears that the margin of the Champlain lobe ice sheet adjusted such that what had been its lateral eastern margin became a frontal margin. Extensive recent glaciological research in Antarctica and Greenland in recent years, suggests that as part of “Glacial Dynamics,” ice sheets and their margins, especially those faced with standing water bodies, are by their nature governed by the laws of physics a) toward equilibration with physiography by the force of gravity and b) to adjust to standing water by the Laws of Thermodynamics. [mfn Its importance is illustrated by the above discussion about Ice Tongue Grooves where it appears that the margin of the Champlain lobe ice sheet adjusted such that what had been its lateral eastern margin became a frontal margin. Extensive recent glaciological research in Antarctica and Greenland in recent years, suggests that as part of “Glacial Dynamics,” ice sheets and their margins, especially those faced with standing water bodies, are by their nature governed by the laws of physics a) toward equilibration with physiography by the force of gravity and b) to adjust to standing water by the Laws of Thermodynamics. Stagnant ice deposits, such as kame terraces, can be seen today on modern ice sheets and glaciers to be forming at very different elevations, along both lateral and frontal margins. Stagnant ice deposits, including many kame terraces, are by far the most abundant ice margin features in Vermont.

The question then becomes how to differentiate frontal versus lateral stagnant ice margin features. Again, as previously noted, in VCGI mapping those stagnant ice deposits which occur as more substantial valley bottom fills were interpreted as being along frontal as opposed to lateral margins of the ice sheet. For example, at an early time the Champlain lobe extended southward in the Vermont Valley where it was confined by the strong physiography of the Valley which is a deep trough between the much higher Taconic Mountains on the west and the Green Mountains on the east. Stewart and MacClintock interpreted stagnant ice deposits they mapped on the floor of the Valley near Rutland and Bennington as significant moraines. Whereas we might quibble over terminology as to whether or not these deposits truly are “moraines,” that argument is beside the point. It seems reasonable to regard these features as having formed at the frontal margin of the lobe tip of the ice sheet in the Vermont Valley, along a margin oriented perpendicular to flow lines, and not its lateral margins.

The Bennington and Rutland deposits represent relatively high elevation features which formed early in Vermont’s deglacial history. To the north of the Rutland and Bennington areas at lower elevations, for example in the foothills between Rutland and Burlington, are many stagnant ice deposits, again especially kame terraces. In this area a distinction likewise was made between those deposits lying against the foothills, which are likely to be along lateral margins, versus those more massive and substantial deposits mapped as major valley fills in tributary valleys, again the theory being that the latter represent deposits formed perpendicular to flowlines and more likely therefore to conform to the “Bath Tub Model.” In fact, numerous stagnant ice deposits along the foothills are step-down types with kame terraces at multiple levels, leading to kame deltas. Those which are more massive in scale and on valley floors were interpreted as having formed on ice sheet frontal margins.

For example, additional evidence which speaks to the validity of the Model comes from local basins. One such example of a local basin is the North Branch Lamoille Basin, which is marked by a succession of progressively lower, and younger step-down stagnant ice deposits representing most, albeit not quite all, of the entire history. The isostatically corrected elevations of these deposits correlate with similar features in many drainage basins under varying environmental conditions. These observations, repeatedly found in many places, led to the recognition that ice margin recession is marked by a record “like multiple rings in a slowly draining “Bath Tub”.” But the more major levels or rings, tend to be recurrent at the same elevations across the state, suggesting an equilibration of ice sheet margins which are correlative. Again, this is believed to be consistent with the thin-ness of the ice sheet. Thus, it turns out that ice margins found in even single basins in some places support the usefulness and validity of the “Bath Tub Model.”

Whereas many ice margin features fit with the concept of the “Bath Tub Model,” lending weight to its validity, in contrast, Ice Tongue Grooves likely indicate disequilibrium where and when, as discussed above, the ice margin was not in equilibrium and not conformant with the “Bath Tub Model.” However, as indicated, once major standing proglacial lakes formed, the ice sheet margin tended to be closely associated with, and likely greatly influenced by, if not controlled by, these water levels. Hence, ice margins for much of the “Bath Tub” history were closely linked with water levels, removing or diminishing the ice sheet surface gradient issue, all of this in conformance with physiography.

Thus, in sum, the idea that elevation and physiography were important and controlling elements during the ice sheet recession, and thus can be used for mapping and correlating ice margin features, and their interpretation using the modified “Bath Tub Model,” as a guiding principle in the interpretation of ice margin features as mapped across the State is supported by the development of a history which is both robust and reasonable. This history entails many pieces and thus makes the determination of deglacial history much more robust than a simple “Bath Tub Model.”

a) It turns out that a) receding ice margins became increasingly fronted by standing proglacial water bodies as a consequence of the “reverse gradient” setting, b) these water bodies mark a step-down sequence of closely related ice margin and proglacial water body features c) these water bodies coalesced and became larger through time, becoming regional water bodies such as Lake Vermont, the Champlain Sea, and large water bodies in the upland interior of Vermont, d)these water bodies developed as increasingly long, narrow and, more or less open water bodies along “Disaggregated” ice margins, e) such ice margins became increasingly controlled and thereby associated with such water body levels, f) such ice margins are marked by proglacial water body features such as kame deltas with evidence of the close and nearby presence of ice, g) as a consequence of such water bodies ice lobes became increasingly convex, h) recession took place in both south to north and east to west directions as lobes became increasingly extended, i) the levels of such ice margins became increasingly controlled by the water levels of these water bodies, j) sudden and substantial changes in the water levels of these water bodies resulted in destabilization of the ice sheet, by which the eastern lateral margin was transformed into a frontal margin with adjustment of ice sheet levels, gradients, flow directions and ice margin levels to closely conform with water levels, and k)) therefore, as a consequence, the usage of a “Bath Tub Model” is more reasonable, defensible, and justified because the close conformance of ice margins to water levels reduces the complicating factor associated with ice sheet surface gradients and other elements which otherwise conflict with “Bath Tub” thinking.

b) The determination of deglacial history is greatly aided by links between ice margins in nearby basins at both the local and regional and statewide scale. For example, Drainage Lines are identified showing drainage from specific ice margins in the Memphremagog Basin over a distance of about 25 miles graded to and therefore equivalent in time to ice margin features in the Lamoille Basin, associated with the strandline of Lake Winooski (a major regional proglacial water body in the interior uplands of Vermont), which in turn can be linked via another Drainage Line into the Champlain Basin and southward in that Basin vis proglacial water levels in southern Vermont, essentially showing a correlation across Vermont independent of the Bath Tub model type correlations.

c) The recession of the ice sheet is marked by features which delineate a Nunatak Phase at an early time in Vermont deglacial history, transitioning into a later Lobate Phase. Whereas this transition began earlier in southern Vermont, this transition is marked by a combination of ice margin features which give a unique “Signature” pattern o ice margin features that can be identified and traced across the State, supporting the usage of elevations in the Bath Tub Model.

The point here is that whereas the “Bath Tub Model” provided a helpful guide for the mapping, correlating, and differentiating ice margin features buy age, its usage was only as a general guide, but that the deglacial history presented here came to be developed by a variety of methods and thoughts, and not just elevation. Nevertheless, to be clear, the usage of physiography and the Bath Tub Model remains an assumption. Geology is an inexact science which by its nature is based on a wide array of such assumptions or principles, which are routinely used. Whereas assumptions by definition cannot be proven, they can be tested. As discussed in the deglacial history section below, eight ice margin levels are identified in the Bath Tub Model for Vermont, which are interpreted as representing discrete times in the deglacial chronology. As noted above, the fact that margins at the same levels can be correlated in many different basins across the State of Vermont, having different environmental conditions or Styles, and in the face of different Glacier Dynamics, suggests that the usage of the Bath Tub Model has merit.

The evidence indicates that the Vermont “Bath Tub” was very irregular with major terrain differences, for example in the Champlain Basin versus the Memphremagog Basin, versus the Lamoille Basin versus the Winooski Basin, versus the Otter Basin, and so on. In fact, the evidence indicates that these terrain differences were very important, resulting in greatly different Styles and Glacial Dynamics. And yet, in spite of these differences, whereas features occur at multiple levels in all these very different physiographic settings, all with recessional features like “multiple rings on a slowly draining “Bath Tub,” the ice margin features identified as being more significant occur at recurrent, correlative, isostatically corrected levels in diverse basins.

The examination of physiography in the usage of the Bath Tub Model for mapping on VCGI was an exercise in deductive and inductive reasoning, involving the identification of ice margin features and the mapping of these along contours, taking into account isostatic rebound. In the process T levels and times were identified. The mapping process was a model building exercise, putting together puzzle pieces involving information pertaining to deglacial history, the nature of the ice margin environment as Styles, and Glacial Dynamics. This model building was a progressive and evolving learning process. Ice margins tend to be complex, requiring the map-maker to “think like a glacier.” What would a glacier do in particular terrain, where would its ice margin extend, how would meltwater be handled? This thought process thus develops many puzzle pieces or parts which fit together in a way that makes geological sense, adding confidence to the Bath Tub Model interpretation.

2. Ice Margin feature elevation uncertainty, variability, and imprecision – the mechanics

Beyond the issue of the validity of the Bath Tub Model as a general proposition is a complicating aspect, which pertains to ice margin feature elevation data uncertainty, variability, and imprecision, having to do with the mechanics of the model application. . If we were to make a graphical frequency plot of ice margin feature elevations the result would show a considerable variation or scatter owing to uncertainty and complications associated with isostatic rebound and imprecision related to the identification and mapping of ice margin feature remnants as markers of T level and time elevations. Statistical scatter reflects the imprecision and uncertainty about the elevations represented by ice margin features, much like water body strandline features. Imprecision and uncertainty stems from different factors. A major factor is the fact that all ice margin dep0sits, by their nature, individually span a range of elevations. For example, stagnant ice deposits, which in Vermont are by far the most common type of ice margin feature, commonly range over substantial elevations as much as one hundred vertical feet or more. In the selection of elevations for stagnant ice deposits in the VCGI mapping reported here, peak elevations of individual deposits, or in some cases predominant elevations, were utilized to establish their representative ice margin elevations. However, this entails subjective judgement, and adds imprecision and therefore variability in the data for deposits formed at multiple locations at the same levels or times. This is further complicated by the fact that post-glacial erosion has removed large portions of stagnant ice deposits, which adds scatter to the elevation data base.

Another example of the same type of problem is provided by kame deltas. Such deposits are very important ice margin features, but these generally are sprawling type deltas(as opposed to Gilbert type deltas), with broad, extensive sloping planar surfaces, commonly spanning fairly substantial elevation ranges. Whereas it is preferable to utilize the elevation of topset/foreset strata contacts in deltas, such information is not available in remote mapping by VCGI. Moreover, deltaic deposits commonly were subsequently eroded with only remnants remaining, commonly across a relatively substantial range of elevations. Picking the elevation of individual kame delta deposits was again a matter of subjective judgement, which unavoidability adds to scatter of elevations for individual levels.

Further, the usage of contours for elevation information, which is provided from USGS data, generally at 10 or 20 foot contour intervals. Whereas this is a relatively small factor as compared to the intrinsic variability in the elevations of ice margin features, this adds to the imprecision.

As a consequence of the scatter resulting from imprecision and uncertainty, the ice margin levels identified in this report are necessarily and intentionally established as elevation ranges. Thus, we have, for example, the T4 ice margin at the elevation range of 1200 to 1400 feet(366- 427 m). The same applies to all eight ice margin levels and times identified in the deglacial history section below.

Added to this, beyond the issue of imprecision and uncertainty as just discussed, an additional point needs to be made, which is that ice margins themselves were not simple knife edges but involved both active and stagnant ice margins, the latter as broad zones, which developed progressively over more prolonged times while the active ice margin was receding. VCGI mapping suggests deglacial ice margins were complex, broad zones marked by both active and stagnant ice margins, with overlapping spatial and temporal relationships, the nature of which varied in different drainage basins in accordance with different Ice Margin Styles in response to Glacial Dynamics, all as dictated by different physiographic settings. This observation is important because we all of us in the deglacial history analysis “business” tend to think of ice margins as sharp lines on a map. The evidence here suggests otherwise.

Glacial Dynamics and Styles add to the complexity and therefore uncertainty and imprecision of the historical analysis given here. This underscores a major point relative to the usage and validity of the Bath Tub Model, which is that the major “rings” on the Bath Tub Model were not narrow or thin marks but rather more like wide or thick blurry blotches extending around a remarkably irregular “Bath Tub” in which the “suds” formed in different ways according to local Style conditions and according to complex Glacial Dynamic. This was a very complex “Bath Tub” and historical process. However, interestingly and importantly, in a sense this complexity ultimately adds strength to the validity of the usage of the “Bath Tub” analogy as a model for deciphering deglacial history.

One of the major issues related to the mechanics of applying the “Bath Tub Model” is isostatic rebound. It has long been known that rebound was characterized by uplift which is generally planar but perhaps regionally was curvi-planar, that the planar inclination or slope apparently varies from place to place, and that the orientation of isobases likewise appears to vary spatially across the region. Further, these differences are matters of opinion which remain debatable and as yet unresolved. Thus, the state of knowledge about rebound is by no means settled.

Obviously, to apply the Bath Tub Model it is necessary to adjust the elevations of ice margin features to take into account the slope and isobase orientation aspects of isostatic rebound. Reported isostatic gradients in the region range from about 3 – 6 feet per mile(0.57 – 1.1 m/km). For example:

- Chapman(1937; 1939) shows Lake Vermont and Champlain Sea Champlain Basin strandlines on two north-south profiles, one for New York features and the other for Vermont features. These profiles indicate that the strandlines for Coveville, Fort Ann and the Champlain Sea at the marine limit are basically parallel, flattening slightly at the Canadian border, with a gradient of about 4.3 feet per mile(0.8 m/km), , as measured along a north-south axis. Chapman also shows isobases which are oriented NE/SW. If the inclination of the sloping strandlines is measured perpendicular to his isobases the strandline inclination would be steeper, about 5.22 feet per mile(0.99 m/km).

Using the Quebec border as the reference point:

- Coveville 785 feet(239 m)

- Fort Ann 650 feet(198 m)

- Champlain Sea marine limit 490 feet(149 m)

- Port Kent 350 feet(107 m)

- Burlington 250 feet(76 m)

- Plattsburg 175 feet(53 m)

However, as can be seen on Chapman’s profiles, the data include considerable scatter. As just noted, Chapman actually delineated two strandline limits for Fort Ann, underscoring the variability. These elevations show the magnitude of water level lowering from Coveville to Fort Ann and from Fort Ann to the Champlain Sea at the marine limit, which was substantial and helps to explain the Glacial Dynamic effect on the ice sheet that was associated with calving.

2. Wagner(1972) (i.e. me) presented a strandline profile giving similar elevations to those of Chapman. The strandlines show a north-south isostatic gradient of about 5.1 feet per mile, isobase orientation is assumed to be east-west. 4 Wagner’s Figure 3 shows multiple strandline data points with considerable scatter. As reported, most of these data points are from deltas with USGS topographic maps used for elevation control. As stated by Wagner, this strandline features entail elevation ranges, which introduces uncertainty in regard to the precision of strandlines. However, the Champlain Sea limit, which also includes the upper limit of mollusk shells, is relatively well defined. Usage of a gradient of 5 feet per mile for comparison of Wagner’s Champlain Sea delta point #72 near Enosburg Falls is marked are at an elevation of 440-460 feet, which when adjusted by a factor of 5 feet per mile gives an elevation of 495-515 feet. This compares with Wagner’s data point S2 near Weybridge at an elevation of about 175 feet, giving an adjusted elevation of 490 feet. If Wagner’s(1972) Champlain Sea strandline is correct, this gives a strong argument and support for using 5 feet per mile as the isostatic gradient for north south adjustments.

3. Calkin (1960s?,ibid, p. 15), who worked in the Middlebury area for S & M, reports the gradient as 4-6 feet per mile. This may be taken from Chapman.

4. De Simone and La Fleur(1985) 5 https://ottohmuller.com/nysga2ge/Files/1985/NYSGA%201985%20A10%20-%20Glacial%20Geology%20And%20History%20Of%20The%20Northern%20Hudson%20Basin,%20New%20York%20And%20Vermont.pdf for the southern Champlain Basin report concave upward curved strandlines, and gradients generally on the order of 2.4 – 2.7 feet per mile(0.45 m/km), but in more northerly areas show gradients of about 1.7 feet per mile(0.32 m/km) for Quaker Springs, 1.6 feet per mile(0.3 m/km) for Coveville, and 1.05 feet per mile(0.2 m/km) for Fort Ann, all with concave upward curvature

5. Rayburn, De Simone, and Frappier (2018) show linear strandlines with a range of levels for Fort Ann due to changing outlet conditions.

6. Parent et Occhietti(1988, Figure 10) show the Fort Ann and Champlain Sea level at the International Border at elevations basically in agreement with Wagner’s levels for both of these strandlines, with a gradient of about 0.9 m/km = 4.75 feet per mile. These authors depict curved, arcuate isobases ranging from almost east-west in the Champlain Basin, to about N10E in the northeastern Vermont to about N45E in the Sherbrooke area.

7. Lewis, 2021, 6 Lewis, C.F., 2021, Reconstruction of isostatically adjusted paleo-strandlines along the southern margin of the Laurentide Ice Sheet in the Great Lakes, Lake Agassiz, and Champlain Sea basins, from Figure 3 in: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Map-showing-the-complex-of-North-American-ice-sheets-during-its-early-deglaciation-when_fig1_223056174. reports profiles indicating a regional isostatic gradient of 4.75 feet per mile( 0.9 m/km) with nearly east west isobases for the Champlain Sea strandlines.

8. Franzi(2024 personal communication) finds a gradient of about 0.92 m/km = 4.9 feet per mile, with east-west isobases in northeastern New York.

9. Wright(2024, personal communication) believes that isostatic gradients were lower than identified by Wagner . However, the local elevation of the outlet for his Lake Winooski at 914 feet(279 m) as compared to the local elevation of Lake Winooski at a verified Wright location along the Worcester Range at 1080 feet(329 m), which is 29 miles(46 km) north of the outlet, gives a gradient along a north-south transect of 5.72 feet per mile(1 m/km). Wright regards the isobases in the interior upland area of Vermont as indicating a slight southeasterly slope.

The different estimates for isostatic gradients and isobase orientations are difficult to reconcile. Wagner’s(1972) strandline for the Champlain Sea maximum gives perhaps the best available data base, in terms of numbers of data points, and has the added benefit that the Champlain Sea marine limit is also marked by mollusk fossils. In this present VCGI report, the 5 foot per mile(0.95 m/km) gradient along a north-south transect is used as an isostatic correction factor, but the mapped strandlines given by Chapman and Wright et al for Lakes Winooski and Mansfield, and Lake Vermont were also used.

In order to correlate ice margin features mapped on VCGI using the “Bath Tub Model,” to correct for isostatic differences, the local, present day elevations of ice margin features were adjusted by adding an elevation determined by measuring the distance from that location to the Quebec border, using an isostatic slope of 5 feet per mile.

Whereas this report assumes and utilizes east-west isobases with isostatic corrections based on north-south transects, the difference between the NS transect versus, a slight NE-SW isobase orientation, as reported by others, results in only slight elevation differences . Clearly, the matter of isostatic rebound deserves further study.

Whereas the entire matter of imprecision and uncertainty resulting from isostatic rebound, as just described, deserves further attention, in the final analysis, to put the issue into perspective, it needs to be recognized that the usage of the Bath Tub Model is not a highly precise exercise. It does not entail, nor does it require, precise elevations. As previously stated, all ice margin levels are reported as elevation ranges, which reflects the variability and uncertainty of the data used for establishing ice margin levels as ranges rather than precise, specific single elevations. For example, if in fact, the isostatic tilt is not 5 feet per mile(0.95 m/km) but closer to 4 feet per mile(0.76 m/km), the maximum “error” factor would be about 150 feet(46 m), given that the distance from the Canadian border to the Massachusetts border is about 150 miles(241 km). But the elevations of all ice margin features would be adjusted accordingly, likely leading to a similar correlation and ice margin chronology, regardless of the isostatic slope difference.

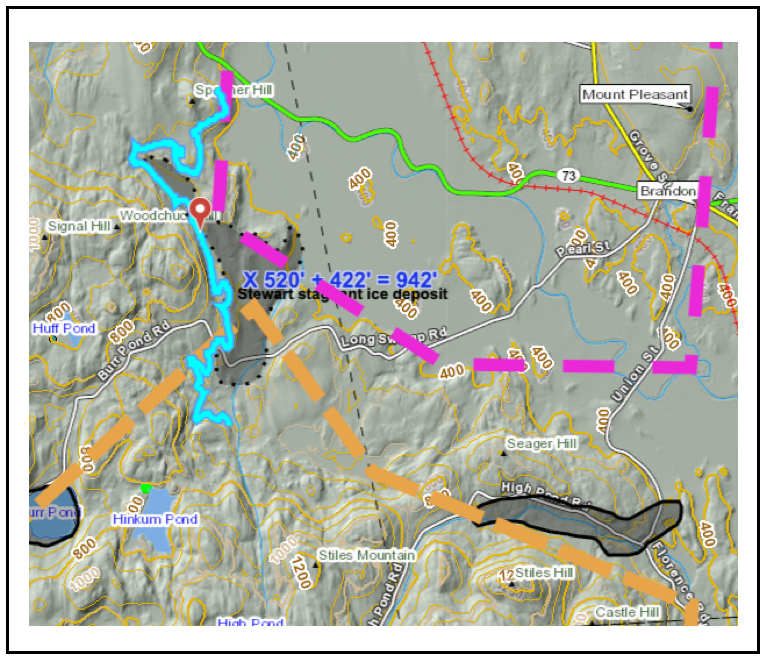

For example, the following is a screen shot of the VCGI map showing the T6 ice margin at a stagnant ice deposit west of Brandon:

The elevation of this deposit is identified as being at 520 feet(159 m), which is shown by the highlighted contour on the screen shot. Using an isostatic correction factor of 5 feet per mile(0.95 m/km), the adjusted or corrected elevation is raised by 422 feet(129 m) based on the distance to the Canadian border of 84 miles(135 km), giving an adjusted elevation for the deposit of 942 feet(287 m), with the Canadian Border as the standard reference point. The elevation range used for the T6 ice margin is 800-900 feet(244-274 m). Whereas the adjusted elevation is 42 feet(13 m) higher than the T6 level range, the deposit was still correlated with the T6 margin, because this elevation is relatively close to the T6 level and fits with other features in the area at the T6 level. The point is that owing to imprecision and uncertainty the Bath Tub Model is not an exact science but is instead an approximation involving considerable subjective judgement.

If in the case of the Brandon feature the correction factor used instead was 4 feet per mile(0.76 m/km) the 520 foot(159 m) elevation would be raised by 338 feet(103 m) instead of 422 feet(129 m), giving an adjusted elevation of 858 feet(262 m) at the Border. Again, this elevation is still within the range of the T6 margin which is 800-900 feet(244 – 274 m). And again, all elevations would be adjusted.

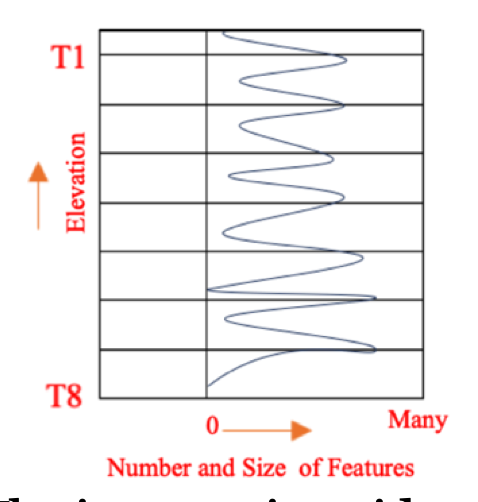

As suggested above, if one were to make a graphical plot of ice margin features versus elevation, the result would show considerable scatter, for the reasons stated.The following suggests what such a graphical plot might look like schematically:

The ice margin evidence in many places in Vermont, again as discussed in detail in the historical section of this report, suggests that Vermont deglacial history is marked by numerous, closely, and relatively evenly spaced ice margin features across the elevation spectrum, but with larger and more numerous features associated with the T levels, commonly as valley fill deposits, as shown on the above graph.

The point of this schematic is that the record of deglacial history is not marked by abrupt changes of ice margin positions from one T level to the next, but instead the record is made up of a multiplicity of ice margins spanning the intervals between T levels, indicating that the ice sheet lowering was progressive and incremental, once again, much like “many rings on a slowly draining “Bath Tub”. This progressive and incremental nature of ice margin recession applies both to intervals between T times and levels, and as well within T levels and times. Many of the T level ice margin features, as for example stagnant ice deposits and kame delta deposits, show evidence, especially on LiDAR imagery, of progressive, incremental recession within individual deposits themselves, and within basins, from the very small scale to Statewide.

Perhaps the T levels represent recession slow down pauses, or “stillstands.” The term “stillstands” tends to carry with it an implied climate variation, but that is not the intent here. Whereas these “stillstands” might represent climatic cooling, three points need to be made in this regard:

- The T levels may represent “stillstands” only in the sense that time was required for the formation of stagnant ice deposits and other ice margin features, more so for more substantial features.

- The ice marginal data are silent in regard to climate. It is possible that climate variations resulted in T levels, but this cannot be, and is not, inferred or implied.

- In terms of Glacial Dynamics, other, alternative factors besides climate can result in “stillstands.”

To elaborate briefly on alternative causes of “stillstands,” a large and diverse literature related to ice margin stability exists, which suggests that “stillstands” may occur due to a variety of factors. The intent here is not to delve deeply into this subject, which is beyond the scope of this report. Intuitively, with regard to “stillstands,” in the context of a Bath Tub Model, it would seem that this might include, for example, controls or influences related to basin hypsometry, physiographic or geomorphic patterns of the landscape geomorphology as part of the regional Appalachian terrain evolution, and standing water levels.

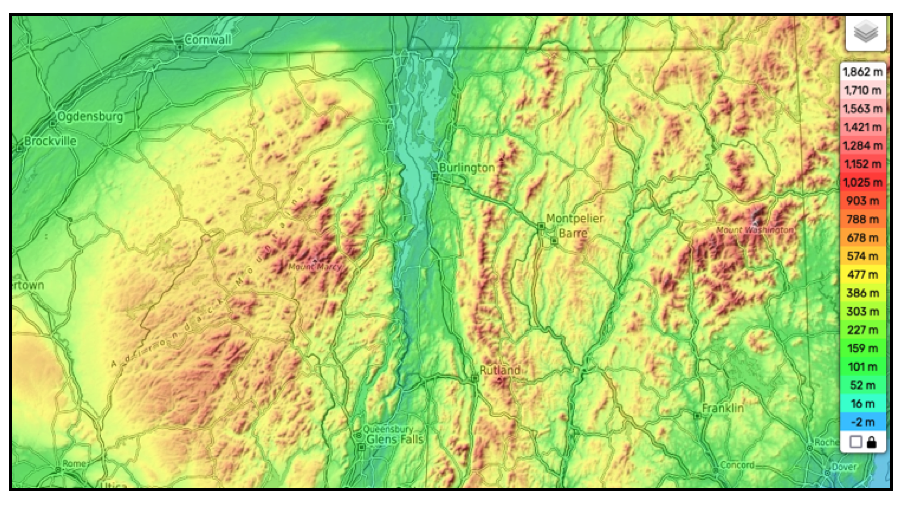

Literature reports make clear that hypsometry of ice sheets and their basins can be a significant factor in ice margin response of different glaciers and ice sheets to climate warming in modern times. The premise here is that the rate of the late Pleistocene retreat of the Laurentide ice sheet margin in a warming climate over a prolonged time varied depending on the ice volumes as the ice sheet receded. This has not been studied for Vermont, but nevertheless makes intuitive sense. It appears that a hypsometric analysis of Vermont physiography has never been done, and in any case doing so in the context of deglacial history would entail evaluating hypsometry of the basin physiography as it existed in late glacial times, before isostatic rebound. Further, in examining hypsometry the question arises as to the extent of the basin being considered, and whether or not just Vermont physiography should be considered, versus perhaps regional Laurentide ice sheet physiographic hypsometry. 7 This point is made more clearly and substantially in a report by Stokes, C.R., 2017, Deglaciation of the Laurentide Ice Sheet from the Last Glacial Maximum, Geographical Research Letters, V 43 Assuming that local, Vermont scale hypsometry may be a contributing factor, a qualitative sense of Vermont hypsometry can be judged visually from present-day physiographic maps. For example, one of the previously presented physiographic maps is again shown below:

This suggests possibly important hypsometric levels with hypsometric “shelves” at the bottom of the yellowish color at about 477- 386- meters(1500 -1266 feet), and below the darker green at 303-159 meters(993- 521 feet). These hypsometric “shelves” represent levels where the volumes of the ice at and below the shelves were smaller than above, and may help to explain the “stillstands” at approximately the T4 1200-1400 foot(366- 427 m) and T6 800 foot(244 m) levels, which were major T levels and times for major stillstands.

The point is not to suggest these observations are correct, but rather to illustrate the idea, or concept, that if deglaciation proceeded like a slowly draining “Bath Tub”, then “stillstands” marked by T levels related to hypsometry are not just possible, but expectable, and not surprising. Hypsometry would seem to be a plausible element in the rate of ice sheet lowering but it is difficult to establish and single out a cause and effect relationship.

As noted above, another factor may have to do with the long term geomorphic evolution of the landscape rooted in geologic history of the Appalachian Mountains. In terms of physiographic or geomorphic patterns, it is noted, as an example, that the elevations of divides between the Memphremagog Basin with the neighboring and Connecticut and Lamoille Basins tend to fall within the 1200-1400 foot(366- 427 m)range. These divides likely are geomorphically related to the long term, geological development of Vermont physiography. Further, these divide areas generally have relatively flat terrain where, when the ice thinned, in fact major stagnant ice deposits at valley heads associated with the T4 level can be found. The ice sheet was opportunistic, with for example stagnant ice features forming wherever ice thickness were insufficient to sustain active ice flow, and where sediment supply was available. Thus, it is possible that geomorphic physiographic patterns may be a contributing factor to the occurrence of “stillstands” at certain levels.

A third element likely affecting deglacial history and “stillstands” is related to the levels of standing water bodies, as already suggested above. Ice margins are closely linked with water levels in the Champlain, Winooski, Lamoille, and Memphremagog Basins, as controlled by drainage outlets. It is believed that this relationship represents a Style and Glacial Dynamic that in fact largely affected if not controlled ice margin levels, with the ice margin chronology closely linked with the proglacial water level chronology, based on evidence discussed elsewhere in this report.

In sum, the preceding discussion examines first the usefulness and validity of the “Bath Tub Model.” It is believed that the Model is useful and valid as a general guide. Second, the above discussion also examines the mechanics of the Model application. While not simple, it is believed that proper mechanics help to make the Model, as just stated, both useful and valid, again as a guide.