In northern Vermont near Bakersfield, on the north side of the mouth of the Lamoille Basin, where it passes from the foothills into the mountains, within the proximity of many Bedrock Grooves and the Ice Tongue Grooves as just described, is a remarkable tract of potholes. These potholes have long been known by residents in the area as part of the local lore. Potholes are not uncommon in Vermont, with some of the better known swimming holes in pothole tracts, such as for example near Huntington and Bolton. However, such tracts generally occur at low elevations on or near valley floors in association with present-day stream beds. What makes the Shattuck Mountain potholes so remarkable is: a) their large size with individual potholes in excess of ten feet in diameter, b) the length of the tract, on the order of 1 mile(most pothole tracts in Vermont are much shorter) c) the high elevation of the tract, ranging from a local elevation of about 600 feet(183 m) to over 1000 feet(305 m)(or perhaps higher from 1300 feet(396 m) , depending on the interpretation), and d) the fact that the tract extends across a regional physiographic divide. This last item is especially notable, in as much as pothole formation requires substantial fluvial discharge and velocity, the levels of which are small or negligible at drainage divides. This points to a glacially related origin.

Whereas scattered incidental reports of upland potholes at high elevations in Vermont are identified online, generally in hiking trail reports, only a few have been reported in the geological literature. Stewart and MacClintock in their Statewide report identify the Shattuck Mountain potholes and briefly mention several high elevation potholes elsewhere in Vermont, but do not provide details. Doll 1 Doll, C.G., 1935-36, A glacial pothole on the ridge of the Green Mountains near Fayston, Vermont; Twentieth Report of the State Geologist of Vermont, pp. 145 – 151.describes a single pothole at a high elevation(2820 feet(860 m) local elevation) on Burnt Mountain near Fayston. Doll states that to his knowledge this pothole represents the highest pothole in New England. Whereas, as he states, potholes can be formed either subaerially by present day streams or sub-glacially during deglaciation, Doll attributes the origin of this pothole to drainage from a Pleistocene ice sheet surface moulin, there being no present day drainage in its vicinity. Interestingly, Ice Marginal Channels on Burnt Rock Mountain are identified at an upper elevation of about 2400 feet (732 m, relatively close to Doll’s pothole, documenting the presence of glacial meltwaters in the vicinity.

a. Cannon versus Wright Interpretations

The Shattuck Mountain potholes were studied, first by Cannon, 2 Cannon, W. F. 1964, Report of Progress: 1964; The Pleistocene Geology of the Enosburg Falls Quadrangle; Vermont Geological Survey Open File Report No 1964-1; 13 p. and subsequently by Wright3Wright, S., 2021, The Shattuck Mountain Channels and Potholes: Evidence for focused high-velocity subglacial streamflow across the northern Green Mountains, Vermont; GSA Paper No. 242-14. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. Vol 53, No. 6

doc: 10.1130/abs/2021AM-369554. Both recognize the potholes as geological features related to glaciation but offer different explanations.

Cannon(1964), again who served as an assistant in Stewart and MacClintock’s statewide mapping project, interpreted the pothole tract as having formed by fluvial action associated with glacial drainage beginning at a high elevation on Shattuck Mountain at about 1300 feet(396 m), descending northward downslope to the divide, where the tract bifurcates with drainage continuing downward on both sides of the divide, one branch to the southeast and the other branch to the northwest.

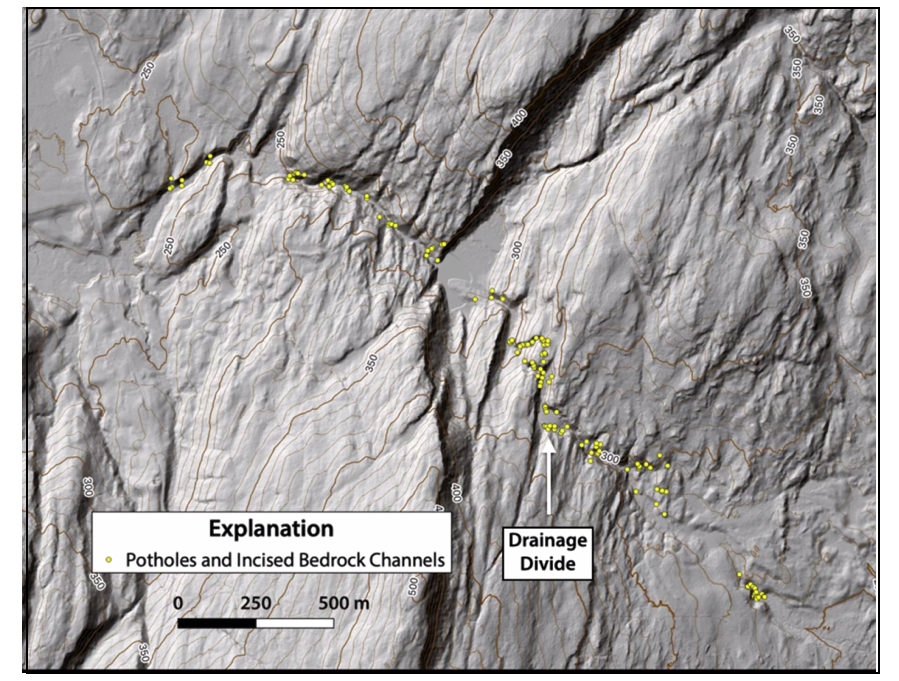

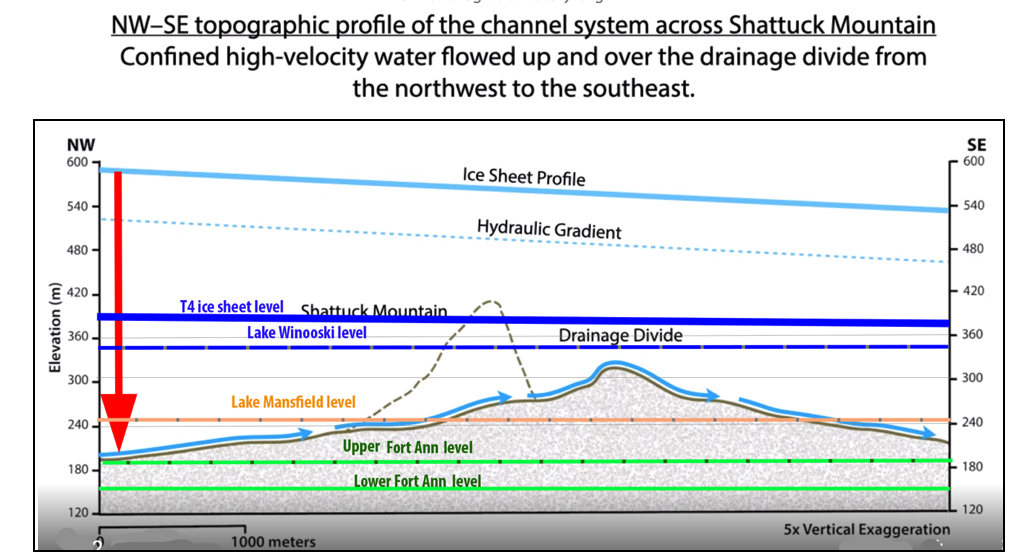

Wright(2021) presented the following map and profile of the pothole tract, the latter with modifications added here as described below:

Wright’s map shows the tract extending across the terrain on both sides of the divide as shown by the yellow circles on his map above and his interpretation of associated drainage by the blue colored arrows on his profile, but does not recognize or include the higher elevation portion on the flank of Shattuck Mountain as described by Cannon. The projected profile of Shattuck Mountain, south of his pothole tract, is given by the dashed black line on the profile.

Whereas Cannon suggests that the pothole tract originated on the flank of Shattuck Mountain in conjunction with glacial drainage, Wright suggests that the drainage in the tract was eastward, beginning at the tract’s western end in the Missisquoi Basin, continuing in an easterly direction up, over the drainage divide, and down into the Lamoille Basin where the eroded material was deposited in a lacustrine deposit. Wright does not provide his evidence for easterly flow (as for example directional evidence from pothole asymmetry in profile or imbricate texture of stones along the tract), or for the lacustrine origin of the receiving deposit. He observes that the elevation of the divide is slightly below the elevation of Lake Winooski, which leads him to suggest the presence of ice blockage to the west, which he further suggests would promote easterly flow in the tract.

To account for flow uphill and over the divide, Wright suggests the tract formation must have involved hydrostatically confined flow in a subglacial tunnel with a higher driving head on the west end of the tract. He suggests that drainage may have originated from a perched lake on the ice sheet surface by downward drainage at a moulin in the vicinity of the red arrow, which has been added here to Wright’s profile above. He infers drainage from the lake may have occurred suddenly and perhaps briefly, with the hydraulic head difference resulting in substantial flow volume and velocity, leading to pothole formation.

b.Literature Discussion

Extensive research in Antarctica and Greenland about potholes and modern day subglacial and moulin drainage, including from supraglacial lakes, has been reported in recent literature. Subglacial water is thought to commonly contribute to surges and ice sheet instability. Scattered reports likewise identify pothole tracts in Pleistocene terrain. According to ChatGPT indicates that such literature includes academic textbooks, scientific journals, and educational websites. Interestingly, ChatGPT states:

“Initially, it was thought that glacial potholes formed from meltwater plunging through vertical shafts, or moulins, in the glacier, directly impacting the bedrock below. This “moulin hypothesis” was widely accepted until the mid-20th century. However, further studies revealed inadequacies in this explanation, leading to the current understanding that potholes are primarily formed by the abrasive action of sediment-laden water in subglacial streams.”4 ChatGPT provides references to specific literature in support of this observation, concluding by noting that this literature which refers to potholes emphasizes the significance of these and other features to “glacier dynamics.”

This statement stems from ChatGPT’s artificial intelligence digital interpretation of published reports in recent literature, and therefore requires further independent literature review to determine if it in fact represents a verified, established scientific consensus. In any case, the literature suggests that subglacial drainage conditions can be quite complex and does not resolve the difference between Wright’s and Cannon’s interpretations. But it is interesting food for thought. Both explanations seem plausible.

c. VCGI Mapping

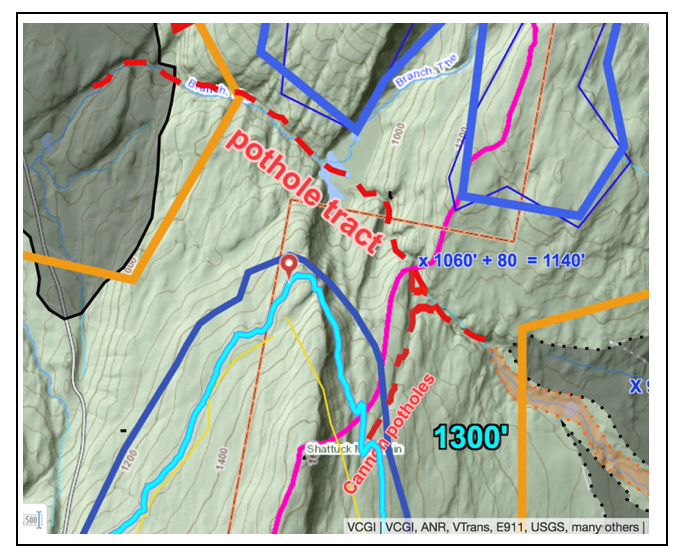

Information obtained from VCGI mapping bears on the issue of the Shattuck Mountain pothole tract formation. The screen shot below shows the VCGI map in the area:

This map shows Shattuck Mountain in the southern portion of the map, the regional physiographic divide marked by the purple line, both the NW-SE and higher Shattuck Mountain pothole tracts by the red dashed lines, and the 1300 foot(396 m) elevation contour by the high-lighted, bright neon blue colored line. Cannon’s north draining tract beginning near 1300 feet(396 m)is labeled. As described by Cannon, this upper portion descends northward to the divide, where it bifurcates with branches continuing into the northwest-southeast tract. Cannon attributes the pothole tract to subglacial fluvial erosion originating at the high, southern end of the upper tract, bifurcating and continuing toward the east and west in the NE/SW tracts.

As stated above, Wright postulates the pothole tract origin is at its western end, by moulin drainage from a higher perched supraglacial lake, with flow continuing eastward up and over the divide to the eastern tract terminus, without recognition of Cannon’s Shattuck Mountain portion.

As shown on the above map:

- The local elevation of the divide at the NW-SE pothole tract is at about 1060 feet(323 m), which adjusts for rebound to 1140 feet(348 m).

- The T4 ice margin and level is marked by the dark blue colored lines. The T4 margin of the ice sheet in the Missisquoi Basin is at an adjusted elevation of 1200-1400 feet(366 – 427 m), with a local elevation in the Shattuck Mountain vicinity of about 1120- 1320 feet(340 m – 402 m). Thus, the T4 ice sheet level is slightly higher than Cannon’s NW-SE portion of the tract, with its margin near the top of this tract.

- Immediately north of the above map area shown above, the T 4(dark blue), T5(orange), and T6 ice margins(maroon) are marked by many stagnant ice deposits and Bedrock Grooves abutting against the western flank of the Green Mountain front range. These Grooves likely formed by fluvial erosion of bedrock terrain from meltwater drainage off the ice sheet, between the ice sheet and the westward sloping bedrock terrain. The tract on Shattuck Mountain identified by Cannon may lie on a Groove at the T4 level and time. But whether or not this contributed to or caused the Shattuck Mountain potholes can not be definitively established.

- At T4 time, the ice sheet in the Champlain lobe entered the Lamoille Basin by generally easterly flow up the Lamoille Basin via the main Lamoille Basin mouth to the south of Shattuck Mountain and as well by passing across the saddle north of Shattuck Mountain in the pothole vicinity.

- The gradient of the ice sheet surface west of the Green Mountain front and therefore the direction of meltwater drainage on its surface in T4 time likely was southeasterly, with Shattuck Mountain, and nearby Wintergreen Mountain, Ryan Mountain, and Gilson Mountain projecting above the ice sheet to form a partial but substantial obstruction. Surface meltwater likely was directed on the ice sheet surface toward the saddle area near the pothole tract. As melting progressed in T4 time with ice sheet lowering and thinning, a low basin for a supraglacial lake in the saddle plausibly may have developed, fitting with Wright’s suggestion of a perched supraglacial lake above the pothole tract, albeit at the divide and not the western end of the tract.

- As well, the map above shows that in T5 time the divide area became ice free, whereby meltwater drainage associated with lowering of the ice sheet from theT4 to T5 level plausibly may have occurred, which would fit with Cannon’s interpretation.

In essence, these observations suggest a unique ice margin Style existed in this area in T4 and T5(and T6) times with the Champlain lobe ice margin abutting a protrusion of the western flank of the Green Mountains and foothills, which favored meltwater erosion of the bedrock terrain so as to deepen and enhance pre-existing bedrock structural elements with the formation of many Bedrock Grooves. Thus, the development of the pothole tract is consistent with and adds support to this Style, including in the manner suggested by both Wright with moulin drainage of a perched supraglacial lake, likely in T4 time, and/or as well by Cannon in T4 and T5 time. It is possible that the formation of portions of the pothole tract formed over a range of time, possibly T4-T6 time, and including both supraglacial moulin drainage and ice marginal drainage, consistent with both interpretations. Subsequent T7 and T 8 levels were well below the pothole tract.

Unfortunately, VCGI mapping is limited by the resolution scales of aerial imagery, which is insufficient to provide more detailed information, and does not resolve the different interpretations for the formation of the pothole tract. However, the information is sufficient to suggest that the pothole tract likely was associated with the formation of the nearby Ice Tongue Grooves in the Lamoille Basin.

In addition to understanding the water source for the tract formation, the linkage between drainage in the pothole tract and the downgradient disposition of eroded sediment from the tract is of interest and in fact necessary for a full understanding of deglacial history. Wright suggests that the pothole tract discharged to the east into a lacustrine deposit but does not specify or elaborate on details. Cannon does not deal with deglacial historical aspects of the tract.

In general, VCGI mapping shows that ice sheet recession in this area, both to the east and west of the pothole tract, is marked by multiple, closely spaced step down level deposits at the T4, T5, and T6 levels, including both stagnant ice deposits and kame deltas. It is likely that the pothole tract drainage was into stagnant ice margins or proglacial water bodies, or both, at these times. However, the VCGI map scale gives insufficient resolution to show the disposition of eroded materials from the pothole tract.

To the east of Shattuck Mountain, in the Lamoille Basin, evidence for Lake Winooski is mapped on VCGI in association with the T4 ice margin level. Immediately east of the saddle area is a stagnant ice deposit, shown by the gray shaded feature on the VCGI map, representing the T4 and T5 ice margin extending into the North Branch Lamoille Basin, with no indication of the presence of Lake Winooski in this vicinity. Evidently in T4 time Lake Winooski was prevented from reaching the Shattuck Mountain pothole vicinity by this ice lobe as part of the Lake Winooski ice dam. VCGI imagery suggests that drainage from the tract may have contributed to this deposit in T4 time and/or eroded through and therefore postdated the stagnant ice deposit, and may be graded to deltaic deposits related to either Lake Mansfield or perhaps Fort Ann Lake Vermont in the Lamoille Basin.

To the west, whereas Wright contends that the pothole tract involved easterly flow, VCGI imagery suggests a possible erosional channel extending westerly from the tract, suggesting a possible contribution to stepdown stagnant ice and local proglacial lake deposits at the T5 level, and/or possibly cutting through and graded to deltaic deposit at the Fort Ann level(the village of Bakersfield is located on a portion of this deposit.)

The levels of Lakes Winooski, Mansfield, and Fort Ann are added to Wright’s profile above, with an upper and lower level Fort Ann level shown to account for the range of reported Fort Ann features as indicated by Chapman’s and Wagner’s strandline profiles. As can be seen, the western end of the pothole tract on Wright’s profile is close to the upper Fort Ann level and the eastern end is slightly above the lower Fort Ann level. This suggests that the pothole tract may have formed in Fort Ann time, but it is possible that the tract formed over a more protracted period of time when water levels fell from higher to lower levels.

Based on VCGI mapping it is concluded that the pothole tract is an ice margin feature which likely represents drainage related to the T4 and/or T5 levels and times by the mechanisms suggested by Wright or Cannon, or perhaps some variation or combination thereof. The possibility is raised that the pothole tract was formed at a time when the ice sheet, as suggested by the nearby Ice Tongue Grooves, became destabilized by the advance of Fort Ann Lake Vermont along the ice margin, just prior to development of an ice shelf along the Champlain lobe’s south facing frontal margin. However, the meaning of the pothole tract, in terms of deglacial history, Style of ice margin environment, and Glacial Dynamic requires more detailed study.

In a sense, the specific origin of the pothole tract, whether in the manner suggested by Wright or Cannon, is a relatively unimportant detail. Either way, in a larger perspective it is clear that the pothole tract is a drainage feature that ultimately relates to deglaciation and regional physiography, in accordance with the bathtub model. It is likely that the upland areas in the vicinity of Shattuck Mountain and the neighboring peaks formed a partial, westward projecting physiographic barrier during ice recession at an early time, again in accordance with the “Bath Tub Model,” whereby drainage would have been obstructed and impounded, helping to explain the pothole tract formation. This suggests the importance of physiography during deglaciation, much as the Middlebury physiographic bench played a major bathtub role in bringing about the calving ice margin in that area.

Finally, it is noted that the Shattuck Mountain Potholes are part of the recessional history as discussed above in regard to Ice Tongue Grooves. The Potholes are not just a curiosity but are believed to be a significant clue about the recessional history and the transformation of the Champlain lobe lateral to frontal margin. In the Ice Tongue Groove discussion it was observed that both the ice sheet and drainage tended to focus on “pivot points.” The pothole tract is one such pivot point in that these are located where a major upland of the foothills served as a buttress for the ice and a collection point for drainage.

Footnotes: