a. Introduction

This study did not begin with the expectation or intent of finding calving ice margins. 1 It turns out that the deglacial history of ice margins, especially calving ice margins, was an exceedingly complex, three dimensional, time transgressive story, made from incomplete puzzle pieces. This complexity for me has been challenging to understand, then to write about, and even now to re-read. I apologize for this, which becomes tedious and difficult to follow. Even though the intent of this section is to simply introduce calving ice margin features I found it necessary to delve into a considerable discussion about the associated history, as a means of explaining the nature of these features. This inevitably makes for a lengthy discussion, lengthier than I would like, with some overlap with the subsequent discussion in a later chapter about deglacial history. The calving margin story suggests that the way I personally have thought about receding ice margins, and I believe more generally as conventionally thought by the larger surficial geology community, represents a paradigm-ic bias that needs rethinking. The resultant story as presented here tries to help flesh out and explore this thinking. This section of my report about calving ice margins could easily and might better serve as an independent report in and of itself. It represents one of the more important findings from my VCGI mapping, not just about deglacial history but as well about global warming. The take-away for me is that the configuration of the physiography of the terrain beneath a glacier or ice sheet, the part we don’t see and find difficult to access in modern glaciers, or in other words the “Bath Tub,” is exceedingly critical to the demise of ice sheets and glaciers faced with global warming. This recognition is not new to me, as has already been reported in substantial literature, but the Vermont story underscores the importance of recognizing and understanding physiography beneath present day ice sheets in this era of global warming. Appendix 4 provides background perspective about how this finding came about. In general, calving ice margins per se have not been mapped previously in Vermont, but as discussed below previously published reports in the Champlain Basin both explicitly suggest the presence of calving or provide information compatible with calving. Different types of calving margin features are identified and mapped in this Basin in this present study. The evidence suggests that calving in the Champlain Basin involved multiple ice streams related to physiography. Calving occurred at different times and locations related to the Champlain Basin physiography and “externalities,” notably the lowering of Lake Vermont from Coveville to Fort Ann levels, and subsequently of Fort Ann to the Champlain Sea level. Further, the evidence indicates that once started, calving was progressive, probably rapid, perhaps beyond a tipping point, leading to the ice sheet’s final exit from Vermont.

Evidence in the Memphremagog Basin, such as bouldery lacustrine silt-clay deposits, is suggestive of possible calving in that Basin. No such evidence was found in the Connecticut Basin. Further study of these two basins in regard to calving is needed, although calving in the Connecticut Basin is unlikely owing to the en masse stagnation of the ice sheet in this Basin for much of its recessional history.

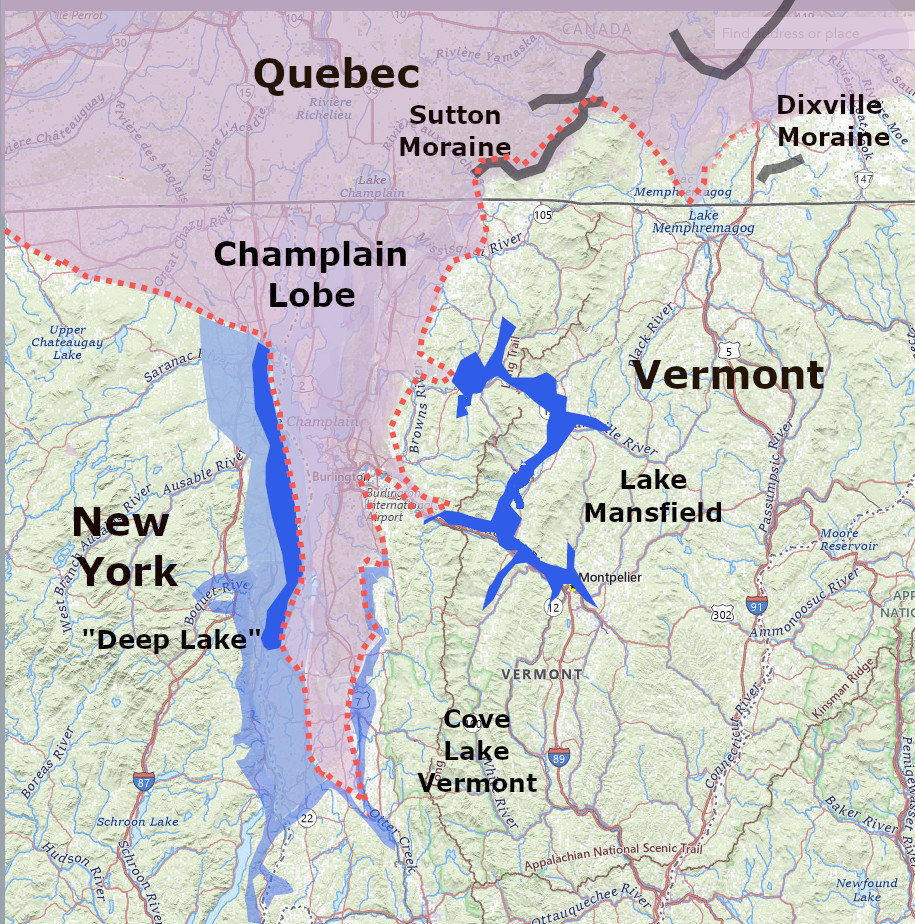

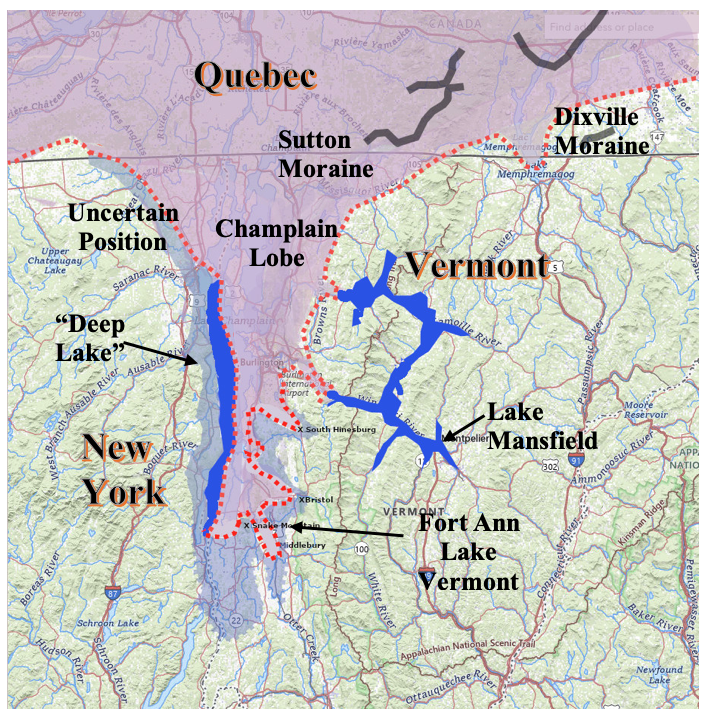

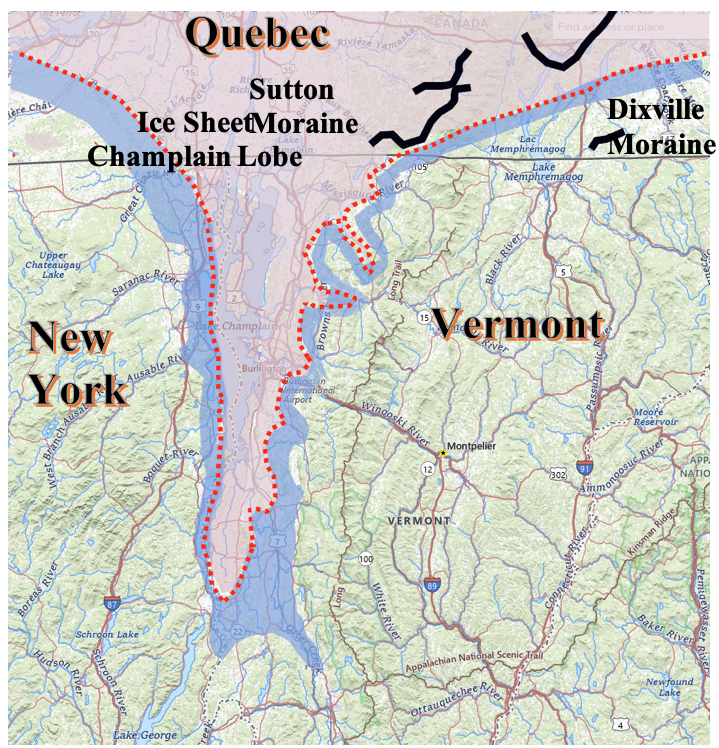

Calving is commonly thought of as causing or resulting in a flattening of ice lobes, with concave indentations in plan view relative to the neighboring, non-calving margins. On the other hand, the lower elevations of Basin floors favors the advancement of ice lobe frontal tips. The interplay between the advancement of the frontal margin versus its recession by calving is a Glacial Dynamic between ice and water. The evidence in the Champlain Basin indicates that this Dynamic favored the development of a long convex ice lobe with a calving frontal tip at multiple ice streams extending southward in central portions controlled by physiographic lows on the Basin floor, with a long, narrow, more or less open, water “Disaggregated” open corridor along its lateral eastern margin.

Further, the evidence indicates that as part of this Glacial Dynamic the history of the recession of the Champlain lobe involved the progressive northward recession of the frontal tip and the northward expansion and widening of an eastern lateral margin open water corridor. As is common with calving, the evidence indicates that the Champlain ice lobe ice was destabilized by calving at the south-facing frontal tip, resulting in rapid northward recession of this ice margin. In addition, the evidence suggests that the eastern margin as well became destabilized by the rapid northward penetration of the narrow, open water corridor, with destabilization of the eastern margin involving its transformation from a lateral to a frontal type margin, entailing a reconfiguration of ice sheet gradients, flow lines, and ice streaming. Thus, while the frontal tip of the Champlain lobe in plan view was flattened by calving, the overall configuration of the lobe shape in plan view remained relatively convex during the recession of the lobe margins, with both northward and westward recession of the Champlain lobe frontal and lateral margins. This history contrasts with the conventional paradigmic way of thinking about the recession of the Champlain lobe, as a more substantially flattened flattened lobe, such as illustrated by the classic work of Chapman and subsequent investigators, which is discussed further below as a “Paradigm Trap.”

Calving ice margins generally are thought of as occurring at the edge of a floating ice shelf where actual calving takes place. And while that is in fact the definition of a calving ice margin, such margins are marked, and thus can be mapped, by deposits and features at and near grounding lines where calving ice shelves are in direct contact with the terrain. The position and configuration of the frontal edge of a calving shelf can be quite different than the grounding line, and likewise the grounding line can be quite different than the adjacent non-calving ice margin. As discussed further below, different types of calving features formed at and mark grounding lines of the calving Champlain lobe.

Further with regard to plan view configurations, grounding lines per se can be either concave or convex, or irregular, and can protrude beyond or be indented behind neighboring non-calving margins, depending on the ice flow and calving dynamics. For example, in regard to the convexity or concavity of calving ice margins, Goliber and Catania(2024) 2 Goliber S. A., and Catania, G. A.(2024), Glacier Terminus Morphology Informs Calving Style; Geophysical Research Letters; RESEARCH LETTER10.1029/2024GL108530, 11 pages. state:

Convexity dominates the identification of different calving styles because floating glaciers experience low basal resistance forcing a transfer of stress to the fjord side walls, creating a concave shape (Cowton et al., 2019). When glaciers are well grounded, this does not occur and ice flux will be largest in the center of the glacier where it is thickest and fastest, creating a convex terminus. Thus, terminus morphology may directly inform floatation conditions for glaciers. As floatation conditions vary over time and space, so too does the terminus morphology and along with it the dominant style of calving.

Reference to the variations in calving terminus conditions in both time and space is significant, because in addition to their spatial configuration variability, calving ice margin positions can be stable, advancing, or receding, and tend to oscillate, with short term, in some cases even daily oscillations related to tidal fluctuations, and as well longer term fluctuations. This is an important observation because it indicates, as has been reported in both studies of modern day glaciers and ice sheets, and as well in regard to Pleistocene records for the Laurentide ice sheet, that calving ice margin grounding line deposits tend to include a mix of materials such as till and interbedded ponded water and fluvial sediments, including structural deformation associated with oscillations. This means that in the study of Pleistocene deposits with calving margins the distinction between oscillations from larger ice margin shifts, including “readvances” of the ice sheet, can be challenging. In this case, both oscillation and readvance evidence is found in association with the calving margin in the Champlain Basin.

Calving ice margins are associated with ice streams, which are faster moving ice within an ice sheet, related to changes in the flow dynamics of the ice sheet caused by or associated with instability. Instability reflects an imbalance and adjustment of ice sheet mass transfer, levels, surface gradients, flow velocities, and flow lines. Whereas calving ice margins tend to be unstable, not all unstable margins are calving. 3As discussed briefly above, ice sheet instability raises questions as to the applicability of the Bath Tub Model and whether calving margins can be correlated with nearby and regional ice margins on the basis of elevation. The evidence indicates that the position and level of the receding ice margin was closely linked to the levels of associated proglacial water bodies. Together strandline features, ice margin features, including both “normal” types and calving types of ice margin features, as described below, show a close correspondence between the ice margin and physiography, supporting the applicability of the “Bath Tub Model.”The evidence indicates that the ice margins of ice tongues penetrating into the Winooski, Lamoille, and Missisquoi Basin mouths (and perhaps as well the Otter Creek Basin mouth) were destabilized by the rapid northward advancement of the narrow eastern open water corridor, but that the frontal margins of ice tongues in these tributary basins were not calving, likely due to inadequate water depths in the standing water bodies impounded by these ice tongues.

b. Review of Previous Vermont Research

The following is a review of previous reports which bear on calving of ice margins in Vermont. It is it is fair to say that it has been generally and widely presumed that calving took place in the Champlain Basin, simply as a consequence of the presence of major proglacial water bodies in the Champlain Basin associated with ice margin recession, which likely were relatively deep, in theory sufficient to support calving. But to date, calving ice margins per se have not been explicitly identified and mapped. As just noted, calving ice margins typically are oscillatory in nature and thus are marked by stratigraphic evidence such as interbedded silt-clay, gravel, and till. However, whereas such evidence has been widely reported in Vermont, the possibility that this may indicate calving margins commonly has not explored. More commonly such evidence has been interpreted as indicating ice margin readvance, which may or may not be the case. The literature review in the following identifies reports which bear on the subject of calving and stratigraphic and/or structrural evudence, even when calving per se is not considered or identified.

It has long been recognized that the receding ice sheet in the Champlain, Memphremagog, and Connecticut Basins was fronted by standing waters. The classic reference on proglacial water body history in the Champlain Basin is by Chapman, who stated: “as the ice front receded a body of water expanded northward in the valley so that the nose of the lobe was continually bathed in water.” This reflects the fact that the recession of ice sheet lobe margins in Vermont were mostly down the regional physiographic gradients, in what today is referred to as a “reverse gradient” setting. Whereas Chapman’s work focused on the delineation of the strandlines of these proglacial water bodies, and not on associated ice margins per se, this simple statement has major implications. If the ice margin was “continuously bathed in water,” as Chapman noted, important questions are raised:

- Where were the progressive ice margin positions in relation to the proglacial lake sequence?

- How are these ice margins marked ?

- What were the prevailing “Styles, ” meaning the environmental conditions at these ice margins?

- How did the ice sheet interact with the standing water, or in other words what were the associated “Glacial Dynamics,” including calving.

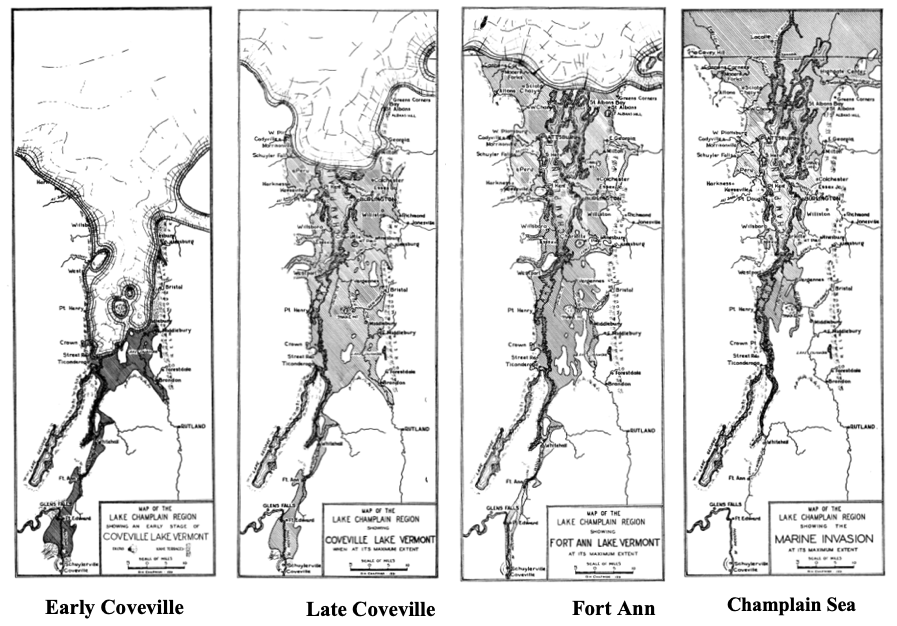

Chapman did not specifically address these issues but inferred ice margin positions for the receding ice margins for early and late Coveville, Fort Ann, and Champlain Sea times, based on his paradigm-ic conception about ice sheet recession, showing the progressive northward recession of ice margins positions in a schematic way as shown by his illustrations below:

Note that Chapman’s illustrations focus on the flattening of the lobe and do not include the development of a narrow open water corridor. In essence, such illustrations and accompanying discussion reflect and build a conceptual model, basically Chapman’s mental image reflecting his understanding or concept of the progressive ice margin recession in the Champlain Basin. As noted above and discussed below under a separate heading, this mental model represents a paradigm, and as suggested poses a “Paradigm Trap.” Without wanting to detract in any way from what was a major advance in our understanding of late glacial and especially proglacial Lake Vermont and Champlain Sea history it needs to be recognized that Chapman’s model was based primarily on strandlines, with little actual, documented basis for his positions of the associated receding ice margins. For example:

- His early Coveville ice margin position is schematic, based on his conceptual understanding that the early position of the ice margin was somewhere north of the Hudson/Champlain divide, but not on actual specific ice margin features.

- His late Coveville ice margin position is based on his understanding of the northernmost Coveville strandline features, but again not based on actual documented ice margin features.

- Likewise, his Fort Ann ice margin is based on his view that the ice sheet remained in Vermont so as to block the Champlain Sea, not on specific ice margin features. 4 In fact, the evidence presented here indicates that in Fort Ann time, this water body extended northward into Quebec while the frontal tip remained far to the south, again , as suggested by preceding comments, indicative of a long convex Champlain lobe.

- And his Champlain Sea time shows the ice margin to the north beyond Vermont, which is based on his view that the Champlain Basin had become open and ice free at this time in order for the incursion of the Champlain Sea, his mental paradigm leading him to believe that therefore the ice margin must have been far removed to the north. In fact, again the evidence indicates that the Champlain lobe projected far to the south in Vermont in Champlain Sea time, as a long convex lobe. (The influence of paradigms on our thinking, including my own, continues to amaze me. We humans need to formulate mental models in order to think about and analyze information, but these models can lead us to incorrect interpretations. As discussed below, the findings presented here suggest that Chapman’s paradigmic bias was incorrect.)

The drawing of ice margins based on inference from strandline information as done by Chapman is reasonable, based on rationale scientific thinking, but necessarily entails a paradigm-ic model, a preconceived rational way of thinking about the nature of ice margin recessions and how we generally think ice margins should look and should have behaved. 5Chapman’s mind set was and still is broadly shared. I too began this present investigation with this model in mind. We tend to think of ice margins as simple lines on maps indicating progressive northward recession. I have learned that this thinking needs to be revisited. Even now, late in the writing process I find myself repeatedly slipping back into my deeply ingrained paradigmic mind set, as for example that the ice margin was a simple, well defined margin which flattened and receded progressively northward. However, the evidence indicates the receding ice margin was a hybrid type, not like a simple line on a map, and that the Champlain lobe retained and may have increased its convexity during recession, with both northward and westward ice margin recession. This is a much more complex paradigmic mental model that is difficult for me to both grasp and describe. Such is the power of paradigms, which hold us in their grasp. This has enormous significance in regard to our thinking about deglacial history in Vermont, and as well bears significantly on the issue of global warming, as discussed further below and in various other sections of this report. Such inference-based thinking may or may not be correct, but in any case it seems obvious that ice margin features themselves give more direct information. This comment is intended to be an undisguised plug for the “Bath Tub Model” and the benefit of mapping ice margins per se as opposed to relying on inference. It is not meant to be a criticism of Chapman’s (or other subsequent research) inferred ice margin interpretations, but simply a recognition that inferential methodology is less precise and more generalized, and can be incorrect and misleading.

As will be demonstrated, while Chapman’s conceptual model is basically correct in a schematic way, the findings here suggest significantly different, more detailed and specific ice margin positions, associated history, Styles, and Glacial Dynamics. Usage of the Bath Tub Model with VCGI mapping helped to delineate ice margins at different times and places in relation to proglacial water levels, and in fact the evidence indicates that water levels largely influenced, likely even controlled the ice margins, strengthening the case for usage of the Bath Tub Model. This observation applies to ice margins from an early to a late time in the deglacial history for much of Vermont, because a) the ice sheet was sufficiently thinned for much of the deglacial history reported here, relative to the scale of the physiographic relief, so that the ice margins were influenced and ultimately controlled by the terrain, and b) ponded water along ice margins had enormous penetrating power and controlling effect on ice sheet dynamics along ice margins through basic ice/water thermodynamic and physical principles of Physics.

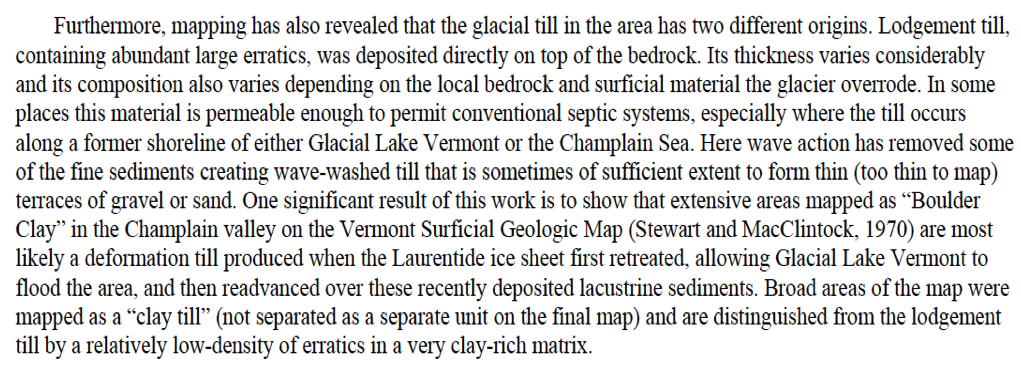

The next major advance in our understanding of deglacial history and information relating to the calving of the receding ice margin after Chapman, albeit again not actual recessional ice margin positions, came from Stewart and MacClintock(1969). Of course, as already discussed previously, these authors had a very different paradigm model in mind about the nature of glaciation and its associated history, one based substantially on stratigraphic and ice movement direction differences, not on the identification, correlation, and delineation of deglacial ice margin positions, including calving positions.

One consequence of their model was that they tended to regard vertical stratigraphic differences as indicative of changing ice sheet movement directions through time, related to their paradigm about glacial history. For example, on page 111 they refer to an exposure in the valley of Lewis Creek where varved lacustrine deposits are overlain by 20 feet(6 m) of glacial till, and another exposure along Little Otter Creek near New Haven where two layers of till are separated by 2 feet(0.6 m) of varved clay. They cite these observations as part of the evidence they use to build a model of glacial history related to three separate glaciations. However, as discussed below, Lewis Creek and Little Otter Creek near New Haven were important locations near Middlebury where the evidence indicates a calving ice margin occurred, possibly explaining such stratigraphic differences in a very different, alternative paradigm way, by a hypothesis related to local ice margin oscillations in a calving setting. Unfortunately, the specific locations of these particular exposures is not given so that independent examination is not possible.

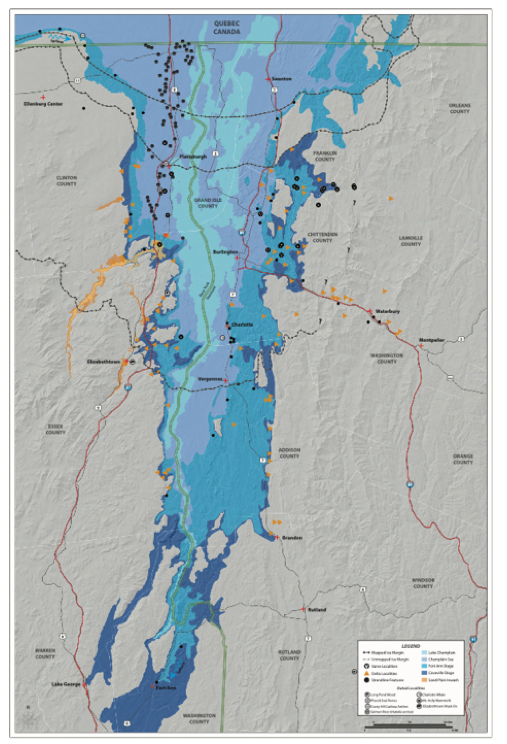

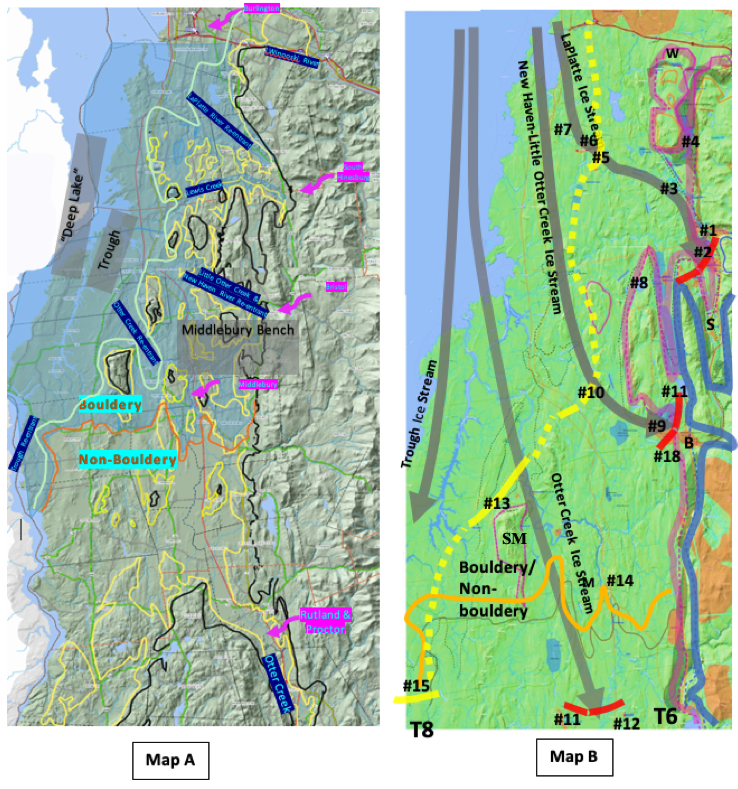

To their great credit, Stewart and MacClintock(1969) identified and mapped the presence of boulders and more generally stones of varying sizes and amounts in proglacial lacustrine and marine silt-clay deposits on the Champlain Basin floor. Such deposits have long been interpreted as indicating a calving ice margin, thought to represent iceberg droppings into proglacial lake or marine bottom sediment. They specifically recognized and suggested the presence of calving ice margins in the Champlain Basin(pp. 160-166, based on the bouldery nature of such deposits in some places, although again they did not identify and delineate such margins at any specific locations. They refer to a ”surprisingly large” abundance of stones in such sediments, so as to “resemble a till plain.” They refer to their State surficial geology map which shows the distribution of both bouldery and non-bouldery lacustrine and marine silt-clay deposits. 6 Based on comments by Connally(1970).who mapped the Brandon and Ticonderoga quadrangles, apparently as part of the then concluding State surficial geologic mapping program, it appears that the bouldery nature of ponded water sediments was determined based on the observations of exposures, and the on the counting of boulders along the margins of farm fields. According to Stewart and MacClintock’s text, the bouldery silt-clay deposits extend northward over a large area on the Champlain Basin floor, northward to the Canadian border, which is likewise shown on their Statewide map, which implied to them that calving persisted as the ice sheet receded northward.

Significantly, Stewart and MacClintock’s State surficial geology map indicates (though they did not so note or discuss in their report) that in the southern portion of the Champlain Basin, their bouldery silt-clay deposits tend to project southward, prong-like, on the basin floor at and below the Champlain Sea marine limit, closely related to its strandline, whereas further north such deposits are associated with both Fort Ann Lake Vermont and Champlain Sea silt-clay deposits all the way northward to the Quebec border. However, silt-clay deposits associated with both Fort Ann Lake Vermont and the Champlain Sea in the main tributary basins, specifically the Winooski, Lamoille, and Missisquoi Basins, are not bouldery on their map. Again, this is likely attributable to the fact that deglaciation and recession of the ice sheet margin was progressive, both from south to north in the main basin and as well from the interior uplands toward the sub-basin mouths, with water depths while ice lobes still occupied these sub-basins being too shallow to support calving.

Stewart and MacClintock refer to what they describe as a virtual absence of till in large portions of the Champlain lowland with lake clays in many places directly lying on bedrock, suggesting to them that the ice sheet may have been calving during both its advance and retreat. This is an intriguing thought, which may bear on the origin and formation of glacial till in Vermont, perhaps with much of it forming at a late time in glaciation. However, this is a topic far beyond the scope of the VCGI investigation here and as well is unrelated to the calving issue.

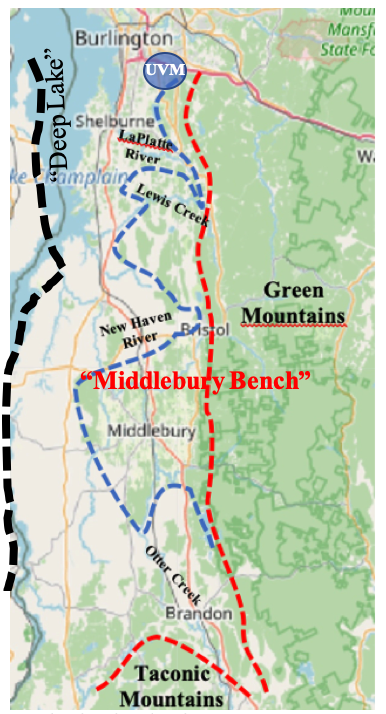

Part of the field work associated with the development of Stewart and MacClintock’s report and map was done by assistants, whose findings are available online as open-file reports associated with the Vermont Geological Survey. One of these is by Parker Calkin(1960s?) 7 Calkin, P.E.(undated) Surficial geology of the Middlebury 15’ quadrangle; VGS open file report VGS-1, 22 pages. This report is undated but believed to be in the 1960s. It is noted that Calkin was a friend and colleague. He became well-known for his research in Vermont, Alaska, and Antarctica. A glacier in Antarctica is named in his honor. He served as a professor at the State University of New York from 1965-1999. He died in 2017. His passing was of course a loss for his family and friends, but as well represents the loss of an opportunity for his personal input here, which no doubt could have been illuminating and helpful. who mapped the surficial geology of the Middlebury area. As mentioned above, and as discussed below, the “Middlebury Bench” area was especially important for the development of calving ice margins. Calkin’s report indicates:

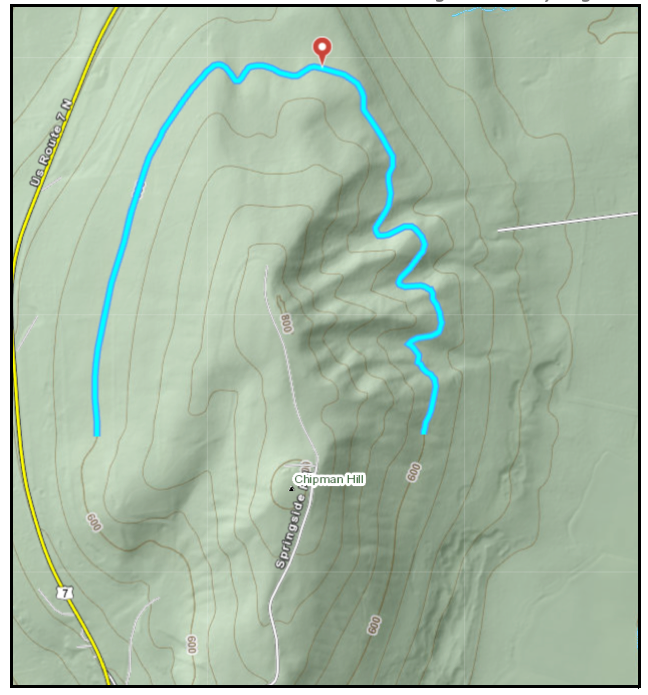

- P 8: On the east side of Chipman Hill(in Middlebury) are ” kame gravels with sandwiched till lenses.” (This specific area and deposit are discussed further below in the section on VCGI results, as part of the evidence identifying and delineating a calving ice margin.)

- P 13: He identified and studied boulder-rich lacustrine clays, stating: “More than half of the vertical cuts in the deposits show that the boulder clays are varved.” This statement was made to lend support to his view that calving in the Middlebury area was significant, and that such bouldery silt-clay deposits were in fact lacustrine, and not till. Calkin suggests two alternative modes of formation of the boulder-rich clays: 1) ice rafting, 2) overriding of lake clays by ice, as documented in places by varved lake clays overlain by till 8Calkin apparently regarded the presence of till overlying other surficial material in an exposure conceptually as an indication of an oscillation or readvance of the ice margin. It is noted here that till interbedded with lacustrine silt-clay is consistent with calving ice margins, and not necessarily an implication of a “readvance.” His overriding alternative presumably is meant to suggest a readvance, though he does not specifically so state.Importantly, he regards ice rafting as the dominant mode of formation.

- Page 19: “The concept of an oscillating ice front may … account for the interbedding of tills and lacustrine deposits.” Calkin does not elaborate on the meaning and significance of this observation, but presumably by “oscillation” he meant a more local and momentary as opposed to larger and longer term “readvance” of the ice margin.

- P 21: “No moraines are evident in the Middlebury Quadrangle. Interbedded tills and lacustrine deposits suggest that there was probably an active and oscillating ice front in the Lowland area …” Again, this statement is taken as representing his opinion about ice margin conditions, which is entirely consistent with the findings here, as discussed below, that ice margins that developed in the Middlebury area and elsewhere were active ice, calving, oscillatory, and destabilized in nature.

In general, as reported in the literature, ice margin oscillations and calving both tend to be part of the same Glacial Dynamic 9 For example: 1) Benn, D.I., et al, 2007, Calving laws, sliding laws, and the stability of tidewater glaciers; Annals of Glaciology, V 46, pp 123-130; 2) Nick, F.M., et al., 2009, Large scale changes in Greenland outlet glacier dynamics triggered at the terminus., Nature Geoscience, V2, # 2, pp 110-114.; 3) Enderlin, E.M, et al, 2013, High sensitivity of tidewater outlet glacier dynamics to shape; The Cryosphere, V 7, #3, pp 1007-1015. and the resultant stratigraphic and structural features do not necessarily infer ice margin readvance. As just noted, Calkin believed that the evidence he found in the Middlebury area supported calving related oscillations. His report gives specific reference to numerous locations which document his findings and interpretations. Whereas many of these have not as yet been independently field checked as part of the present study, VCGI mapping as discussed below provides substantial evidence of calving in the “Middlebury Bench” in a manner consistent with Calkin’s report.

Continuing with the review of previous research in Vermont in chronologic order, in the late 1960s and early 1970s Wagner (ie., me) mapped the area from the Quebec border southward to the Middlebury area (as published in various reports, but with the recessional ice margin evidence largely unpublished). This mapping showed textural, structural, and stratigraphic variations within glacial till and lacustrine deposits but these were interpreted simply as “normal” variations within such deposits. The presence of clasts within lacustrine deposits was recognized and noted, but a distinction between bouldery and non-bouldery deposits was not made. As noted above, my attempts to identify, delineate, and correlate ice margins of any kind, whether “normal” or calving, were unsuccessful. However, in the Missisquoi Basin, silt-clay and till deposits were identified as a veneer on portions of Champlain Sea deltas, which was interpreted as indicating a readvance of the ice margin. As noted above, mapping by Cannon as part of Stewart and MacClintock’s statewide mapping program also reported similar evidence in this area. Again as discussed below, this readvance is believed to be part of the receding Champlain lobe history, with evidence of both calving and a readvance.

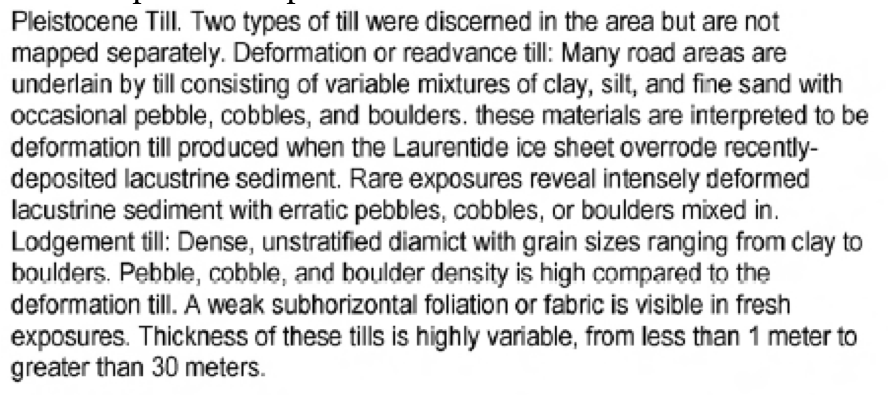

Connally(1970) 10 Connally, G. G.(1970), Surficial Geology of the Brandon-Ticonderoga 15 minute Quadrangles, Vermont; Vermont Geological Survey, Studies in Vermont Geology No 2, 32 p./mfn]mapped the Brandon-Ticonderoga Quadrangles, in the southern Champlain Basin in the vicinity of the aforementioned tongue-like projection of bouldery marine silt-clay deposits mapped by Stewart and MacClintock. 10Whereas Connally refers to the bouldery silts and clays as being “lacustrine,” most of these deposits southwest of the Middlebury area lie below the Champlain Sea limit and thus likely are marine, with the limit of the bouldery silt-clays very closely corresponding with the Champlain Sea strandline. Connally describes his identification of a different type of till in ground moraine on the Basin floor generally in the “lake shore province,” more specifically in the “Otter Creek province.” Glacial till is described in this area as being stony to bouldery with a sandy-loam matrix, as contrasted with till elsewhere which tends to have a clay-loam matrix. He identifies a locality near Bridport where he interprets the till as indicating that the ice sheet overrode “lacustrine” 11Reference to this being “lacustrine” appears to be a generalization in as much as the Stewart and MacClintock map indicates that these silt and clay deposits are below the marine limit.sediment and redeposited the material in a “more or less undigested form.” And he reports two lines of evidence indicative to him of a readvance of the ice sheet:

- A pit exposure near West Bridport which he interprets as indicting that, “bouldery lacustrine clays have been badly contorted, suggesting overriding and incorporation at the base of a glacier.” His Plates 5 and 6 are photographs said to depict till overlying gravel which he interprets as outwash or lacustrine gravel, portions of which are incorporated as shear planes in the overlying till.

- “Ice- rafted boulders present in the lake clay,” generally southwest of Middlebury.

In essence, Connally is interpreting the evidence as indicating a readvance, which approximately corresponds with the bouldery silt-clay soils shown as the projection on Stewart and MacClintock’s map, and in fact this projection likely reflects Connally’s direct input into this mapping. It is believed that Connally’s mapping was part of the Stewart and MacClintock Statewide mapping team, and that his mapping was responsible for some of the boulder silt-clay delineation on the State map. As noted above, Connally describes a method of counting of boulders along tree lines as providing information for delineating bouldery-ness. In a later report, Connally and Cadwell 12Connally, G.G. and Cadwell, D.H., 2002, Glacial Lak Albany in the Champlain Valley, in the field guide for the 71st Annual Reunion, Northeastern Friends of the Pleistocene guidebook, pp B81 – B817. further discuss this readvance evidence, making clear that in their opinion it represented a significant advance of the ice sheet associated with a prior recession of the Champlain lobe. Whereas the evidence for such a readvance as a major historical event has been questioned by subsequent researchers, the photographs given in Connally’s report are impressive, clearly indicating ice margin dynamics. The evidence mapped here on VCGI fits with oscillations associated with a calving ice margin as described by Connally, but neither precludes nor requires a readvance.Interestingly, in as much as both Calkin and Connally were on the same team, we might imagine that their different views may have led to some interesting discussions. From an objective point of view, whereas both interpretations may have merit and are possible, because the concept of a readvance carries with it a more significant implication regarding deglacial history,it is preferable to consider all possibilities before reaching a readvance conclusion. Calkin clearly preferred such caution.

As a side bar:

To be clear, Connally does not specifically recognize, consider, or address calving per se. However, his findings are of particular interest because his work is in the area of the bouldery silt-clay soils projection, within the Champlain Sea footprint, which he and Stewart and MacClintock linked to calving. As just stated, and is repeated here for emphasis, “The evidence mapped here on VCGI fits with oscillations associated with a calving ice margin as described by Connally, but neither precludes nor requires a readvance.” This is such a critical issue that it deserves elaboration, in the context of how my thinking evolved, both in regard to a readvance and the linkagwe to the Champlain Sea.

At an early time in writing this report I tended to be skeptical about Connally’s “Bridport Readvance.” But as just noted, Connally’s evidence suggests “something was going on,” so to speak, in the Bridport area. My early inclination was to suspect this “something” was calving.

Fast forwarding, also as discussed below, I subsequently reviewed the reports of Springston and Wright in the Charlotte area. These authors likewise identified stratigraphic and structural features associated with both interbedded silt and clay soils and sandy soils , which they interpreted as a readvance. Again, I initially suspected that this evidence may instead be related to calving, which likewise was not recognized or considered by the authors as an alternative hypothesis explanation for such deposits. Further, at least some of these deposits are within the Champlain Sea level.

As I was pondering the issue of readvance versus oscillation, and recognized the linkge to Champlain Sea time I also had in mind the evidence that I identified back in the 1970s in the Missisquoi Basin, involving stratigraphic differences, such as interbedded gravels and silt-clays. Such deposits likewise had been identified previously by Cannon. In my opinion, whereas these deposits might represent calving, the fact that they include glacial till overlying Champlain Sea deltaic deposits to me clearly indicates a readvance of the ice margin, again clearly at Champlain Sea time.

Whereas the Connally Bridport evidence and Springston and Wright’s evidence might be interpreted as oscillation related deposits associated with calving, the Missisquoi Basin evidence is more compelling as a readvance. The question then turns to how to account for all three of lese locations associated with ice presence in Champlain Sea time.

In this present VCGI mapping the ice margin associated with the readvance in the Missisquoi Basin is identified as the T8 margin in Champlain Sea time at the marine limit. In my original, early VCGI mapping the T8 margin was traced westward, from the Berkshire and Enosburg Falls area to the Greens Corners area, where Ice Tongue Grooves were identified at the mouth of the Missisquoi Basin. Interestingly, these features indicate early fluvial drainage along receding ice margins at the marine limit, progressing to ice margin positions graded to Champlain Sea deltaic deposits slightly below and therefore younger than the marine limit.

The issue I was then confronting as I was building my understanding was, having demarcated the T8 margin as marking a lobe in the Missisqioi Basin associated with a readvance, where did the ice margin extend. Because my mental model, or paradigm, had in mind calving, it was easy for me to presume that the T8 margin near Greens Corners extended westward across the Basin as a flattened calving margin toward New York State. This was my way of dipensing with the issue, slipping it under the rug so to speak, letting New York researchers deal with the issue of the continuation of the T8 margin. In essence , I was unknowingly operating under the same paradigmic conception as Chapman.

But, I also had in mind the Connally and Springston & Wright. Further, in southern Vermont on the floor of the Champlain Basin in the area west of Vergennes are unusual, suspicious looking features on LiDAR imagery, which were identified as “Ice Marginal Lines.” These features were not back then at that time understood, and their meaning is still uncertain. In time I came to suspect that these may be Mega-Scale Lineations relating to calving. But these are at low elevations in association with Champlain Sea deposits near the marine limit, such that if they are somehow related to an ice margin the implication would be that perhaps the age of the associated ice margin likely would be quite young, perhaps somehow correlated with the Missisquoi Basin T8 margin.

Conceptually, the issue before me was whether the Champlain lobe extended southward on the basin floor as a long convex lobe, with such projection facilitated by the low elevation of the Basin floor – versus alternatively that calving resulted in a receded, flattened ice marin restricted to the north of the Basin. This concept obviously relates to a Glacial Dynamic whereby the ice sheet is driven to extend its margins into lowlying terrain, versus the tendency of calving, if present, to cause substantial recession. In those early days of my VCGI mapping, the calving theory won, such that I drew the T8 margin so as to extend across the northern portion of the basin as a flattened margin, as just stated. This reflected the power of my then existing mind set, or paradigm.

I also was grappling with the realization that the bouldery silt clay soils on the Stewart and MacClintock map were located on the low floor of the Basin in a projection which closely corresponds with the Champlain Sea at the marine limit. This too was a clue.

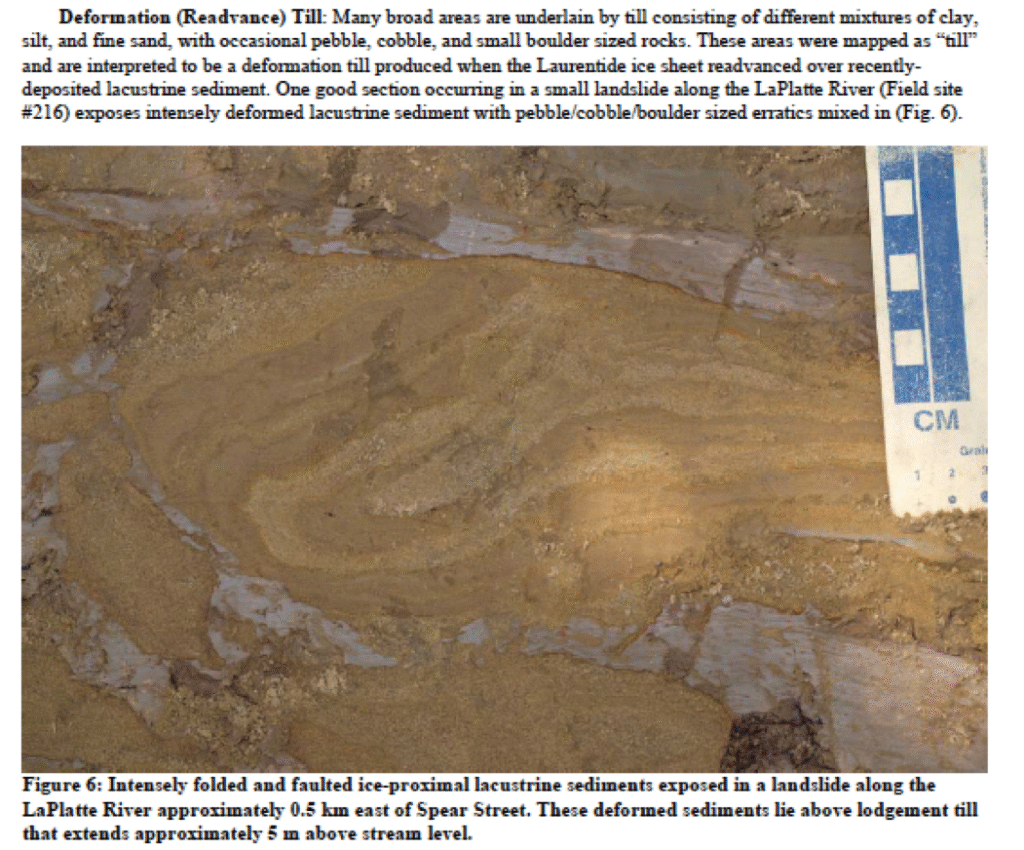

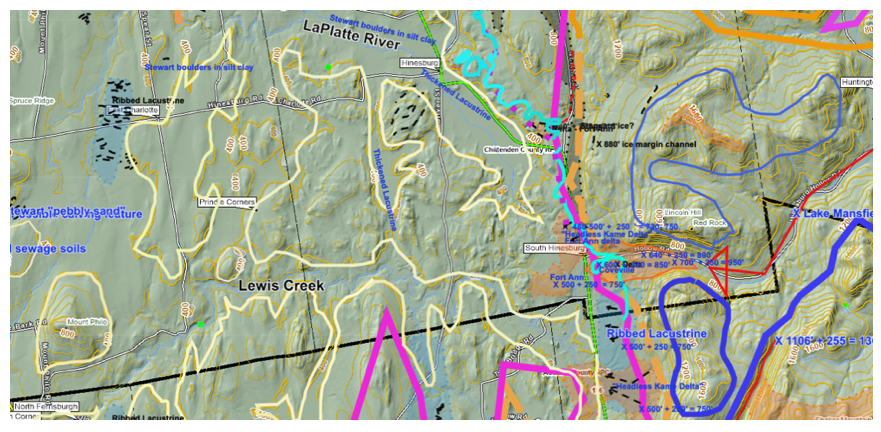

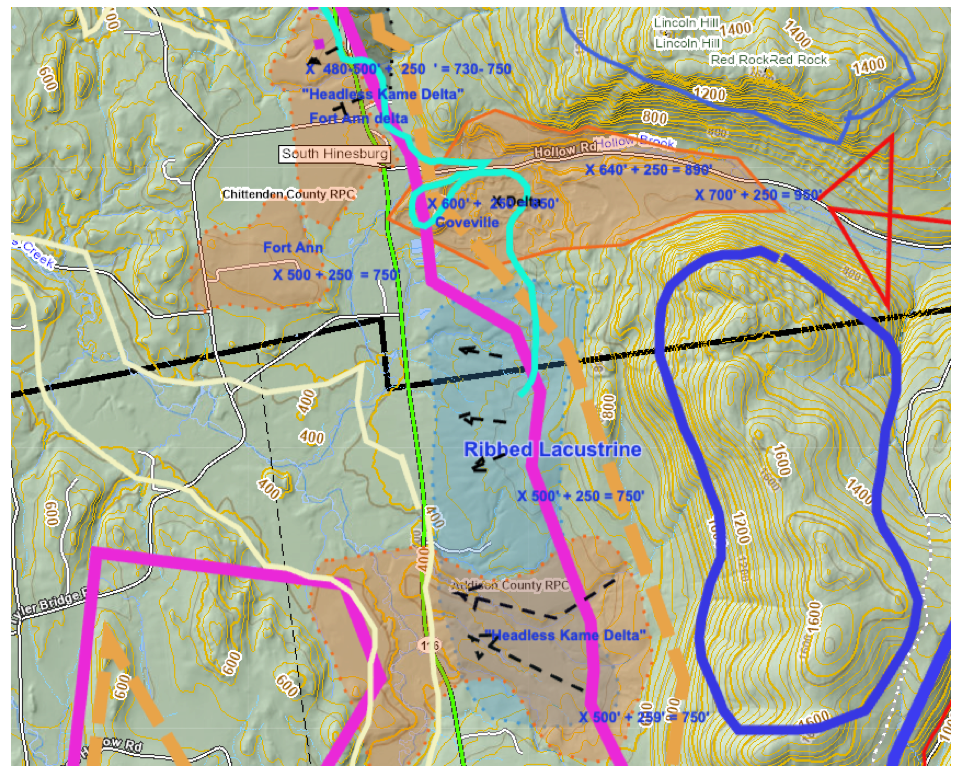

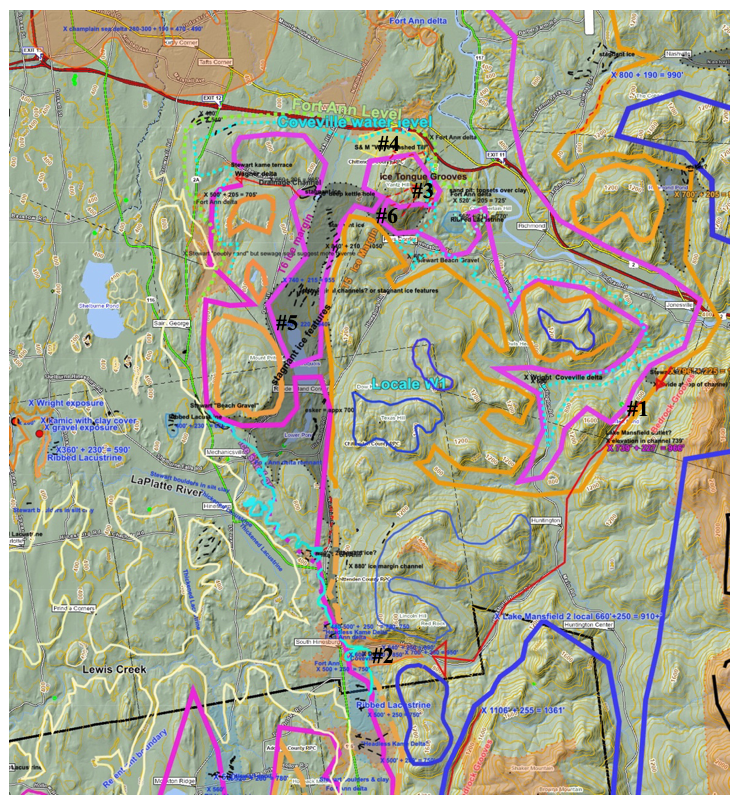

My original interpretive model as just described began to breakdown in my study of the LaPlatte Basin. As discussed below, the evidence in this Basin documents the development of a T7 calving ice margin for a LaPlatte ice stream, beginning in the headwaters of this basin when Coveville Lake Vermont lowered to the Fort Ann level. Multiple calving ice margin features in this Basin suggest the progressive westward recession of this calving ice margin, down the La Platte Basin, in Fort Ann and T7 time. In his Charlotte report Wright identified an exposure along the LaPlatte River near Spear Street, showing structural deformation of till and interbedded sand, at an elevation which is at or close to the marine limit of the Champlain Sea. My VCGI mapping identified a Ribbed Lacustrine Deposit on LiDAR imagery nearby, just upstream from Wright’s deformation exposure. Field examination by me in 2025 confirmed that this deposit in fact includes a surface layer of silt-clay beneath which is a substantial gravel. My understanding of such deposits is that they mark the ice margin, with a stagnant ice deposit which was left behind with ice still remaining buried within the deposit, when rapid ice margin recession allowed these deposits to become veneered with an overlying silt-clay stratum, again while the stagnant ice still remained, with melting resulting in linear elements in the overlying silt clay material. This is my general explanation for Ribbed Lacustrine deposits, based on my examination of many such features in the 1970s, but especially more recently on VCGI, and by recent field visits.

BUT, this Ribbed Lacustrine deposit is at the downgradient end of the Fort Ann calving ice margin recession, near and just above Wright’s exposure, which is at the Champlain Sea level. Further, an exposure nearby to the west (at the La Berge farm), as discussed elsewhere herein, which was mapped by Stewart and MacClintock as a stagnant ice deposit, was examined in 2025, showing this deposit to be a Champlain Sea delta, with soil evidence of a nearby high energy source (ie, ice)!

Thus, I was struck by an “Epiphany,” regarding all the aforementioned evidence on the LaPlatte, specifically that:

- The Ribbed Lacustrine deposit marked a calving margin formed at the end of Fort Ann time, when the water level lowered to the Champlain Sea level,

- The ice margin at that time was either an oscillatory type calving margin or a readvancing margin, or both, resulting in Wright’s “Deformation Till” and the unusuial deposits in the Champlain Sea delta at the LaBerge farm.

- In fact, the La Platte River itself follows a pattern which is consistent with such an explanation, with the River changing course where it lowered from the Fort Ann floor to the Champlain Sea floor. (Such control of drainage patterns likewise has been noted for Little Otter Creek, New Haven River, and Otter Creek.)

- Thus, the T8 margin likely extended southward to the vicinity of these LaPlatte features. And in addition, the T8 margin likely correlates with the the bouldery silt-clay projection identified by Stewart and MacClintock and as well the “readvance evidence reported by Connally.

This exlplantion does not establish that the ice margin at T8 time in the La Platte Basin was oscillatory as with a calving margin, or readvancing, or both. However, the linkage all of these features at the T8 level and time thus come together, specifically including the evidence of a readvance of the T8 margin in the Missisquoi Basin. Further, the evidence cited by Calkin in the Middlebury area fits with the extension of the T7 and T8 margins southward across the Lewis Creek, New Haven River, and Little Otter Creek Basins, as a readvance inT8 time. Thus, multiple pieces of evidence come together to construct a more robust interpretation of deglacial history for these times and locations.

This sidebar is giving an advance preview of how my thinking evolved on the issue of calving as I was reviewing the literature. Calving is now identified as part of the late T6 to T8 recession, with three separate calving events. And further, this recession was marked by a long lobate shaped Champlain lobe, such that the T8 margin occupied the Basin floor, marked by calving and a readvance in T8 time. This evidence includes the progressive recession of the eastern margin via calving recession in multiple ice streams, as the eastern margin transitioned from a lateral to a frontal margin. At the same time the south facing margin likewise receded by calving, but the Glaciar Dynamic between the ice sheet and the ponded water resulted in the recession from the Brandon area northward in T8 time to the Quebec border, for the ice sheet’s final exit from Vermont. This finding is based on the cumulative input of multiple evidentiary pieces, which together suggest that this recession might be likened to a “collapse” beyond a “tipping point.” This observation reflects the fact that in T8 time the Champlain lobe extended southward to the Bridport vicinity, a distance of about 70 miles, but by the end of T8 time the Champlain lobe in Vermont was gone.

This sidebar is making the point that whereas calving is now identified as part of the late T6 to T8 recession, with three separate calving events. And further, that this recession was marked by a long lobate shaped Champlain lobe, such that the T8 margin occupied the Basin floor, marked by calving and a readvance in T8 time. This evidence includes the progressive recession of the eastern margin via calving recession in multiple ice streams, as the eastern margin transitioned from a lateral to a frontal margin. At the same time the south facing margin likewise receded by calving, but the Glaciar Dynamic between the ice sheet and the ponded water resulted in the recession from the Brandon area northward in T8 time to the Quebec border, for the ice sheet’s final exit from Vermont. This finding is based on the cumulative input of multiple evidentiary pieces, which together suggest that this recession might be likened to a “collapse” beyond a “tipping point.” This observation reflects the fact that in T8 time the Champlain lobe extended southward to the Bridport vicinity, a distance of about 70 miles, but by the end of T8 time the Champlain lobe in Vermont was gone.

Whereas the Connally Bridport evidence and Springston and Wright’s evidence might be interpreted as oscillation related deposits associated with calving, the Missisquoi Basin evidence is more compelling as a readvance. The question then turns to how to account for all three of these locations associated with ice presence in Champlain Sea time. This explantion does not establish that the ice margin at T8 time in the La Platte Basin was oscillatory as with a calving margin, or readvancing, or both. However, the linkage all of these features at the T8 level and time thus come together, specifically including the evidence of a readvance of the T8 margin in the Missisquoi Basin. Further, the evidence cited by Calkin in the Middlebury area fits with the extension of the T7 and T8 margins southward across the Lewis Creek, New Haven River, and Little Otter Creek Basins, as a readvance inT8 time. Thus, multiple pieces of evidence come together to construct a more robust interpretation of deglacial history for these times and locations.

This explantion does not establish that the ice margin at T8 time in the La Platte Basin was oscillatory as with a calving margin, or readvancing, or both. However, the linkage all of these features at the T8 level and time thus come together, specifically including the evidence of a readvance of the T8 margin in the Missisquoi Basin. Further, the evidence cited by Calkin in the Middlebury area fits with the extension of the T7 and T8 margins southward across the Lewis Creek, New Haven River, and Little Otter Creek Basins, as a readvance inT8 time. Thus, multiple pieces of evidence come together to construct a more robust interpretation of deglacial history for these times and locations.

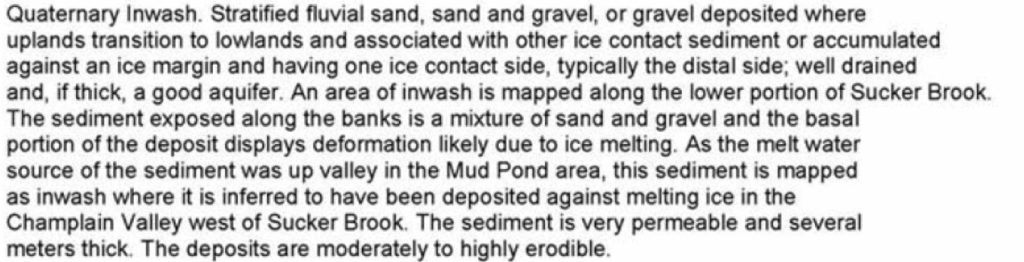

Having given this overview introduction, we can now return to the review of previous literature.Springston and DeSimone (20070 13Springston, G. and DeSimone, D.(2007) Surficial Geologic Map of the Town of Williston; Vermont Geological Survey Open File Report VG07-5. . mapped the surficial geology of the Town of Williston, which is on the northern margin of the “Middlebury Bench.” This mapping was previously referred to as part of the discussion of Ice Tongue Grooves. So far as is known, no report accompanying this map is available. This map includes an area of stratified fluvial sand and gravel along Sucker Brook which is described as follows:

As discussed below, this deposit and an associated deposit further north on Sucker Brook at a higher elevation are here interpreted as kame delta deposits associated with the Coveville and Fort Ann levels related to the calving ice margin in the “Middlebury Bench” area, and the drainage of Lake Mansfield prior to the opening of the Winooski Basin for the invasion of Coveville and Fort Ann waters into the Winooski Basin. While the authors did not suggest calving, this description is included here as part of this review of previous work which is here regarded as supporting calving. Sucker Brook lies along the eastern margin of a small physiographic re-entrant which the evidence below indicates was occupied by a calving ice stream as a small appendage of the Winooski ice tongue. Springston and DeSimone’s mapping fits with and supports this interpretation.

Again it needs to be said that Springston and DeSimone’s work does not explicitly refer to calving, but nevertheless is interesting in that such stratigraphic features as they reported may be related to the calving ice margin story.

Springston and Wright et al and Wright(2009) 14Springston, G. and Wright, S., 2009, Open File Report VG09-6-Surficial Geologic Map of Charlotte, Vermont; VT Geol. Sur.. , 2010 15 Springston, G.. 2010, et al, 2010, Geology and Hydrogeology of Charlotte, Vermont, Vermont Geological Survey, Department of Environmental Conservation, 21 p. This report includes a separate Open File Report VG09-6: Surficial Geologic Map of Charlotte, Vermont, by Springston, G. and Wright, S. pp 16-19, and a separate repot Wright, S. F., Surficial geologic map of northern Charlotte, VT: Report submitted under contract to the VT Geol Sur, VT Dept Env Cons, 11 p. studied the nearby Charlotte area, which is close to and slightly north of Middlebury. The authors recognized soil differences:

- In their description of map units:

- On p. 2 of the associated Wright report:

- On page 6 of the Wright report:

- On page 10 of the Wright report, the author depicts the photo below:

- Wright makes the following statement:

As discussed further below, Wright’s interpretation is believed to be generally correct, but fits as well with both ice margin oscillations and a readvance, though here believed to have occurred in Champlain Sea and not Lake Vermont time as part of the aforementioned long convex Champlain lobe. The type of evidence given by Wright, makes it difficult to distinguish between an ice margin readvance versus ice margin oscillations. However, the evidence presented here in this report from VCGI mapping indicates a correlation of the features described by Wright in the Charlotte area, including specifically along the LaPlatte River, with the evidence presented by Connally in the Bridport area and the evidence presented in the Missisquoi Basin by Cannon and Wagner, greatly strengthens Wright’s interpretation. It is believed that the ice margin readvance was oscillatory in nature during the ice margin recession and/or readvance. Further, Wright correlates this readvance with evidence reported by him and his colleagues in the Winooski Basin, which in turn may be correlated with a readvance associated with the White Mountain Moraine System (WMMS) in New Hampshire. However, the Winooski and WMMS readvances are here believed to have occurred at a previous time, before the readvance associated with the Champlain Sea time features

On page 11 of the Wright report it is stated that the Champlain Sea limit in the Charlotte area is at an elevation of approximately 295 feet(90 m) (which is close to the elevation of his deformation exposure on the LaPlatte near Spear Street), and that, based on soil cores obtained from the Winooski area, the approximate 100 meter drop of water levels from Lake Vermont to Champlain Sea was sudden. The significance of both of these observations relative to the interpretations given here is obvious. The magnitude and suddenness of the change from Lake Vermont to the Champlain Sea is here believed to have been a significant trigger for further ice margin destabilization by calving as a “Glacial Dynamic.”.16The fact that the Champlain lobe calving was associated with multiple times of water level lowering, the first from Coveville to Fort Ann and the second from Fort Ann to Champlain Sea , makes it difficult to definitively establish whether or not the calving recession of the Champlain lobe reached a “trigger point” beyond which the lobe was unable to recover. Further, based on the evidence suggesting that the ice margin in the Missisquoi Basin remained and continued to recede and was still present in later Champlain Sea time when sea level lowered owing to isostatic uplift, suggests that continued recession (including by calving) may have been a response to ongoing water level lowering.

- On page 17 of the Springston and Wright report:

- And on pages 10- 20 of the Springston and Wright report:

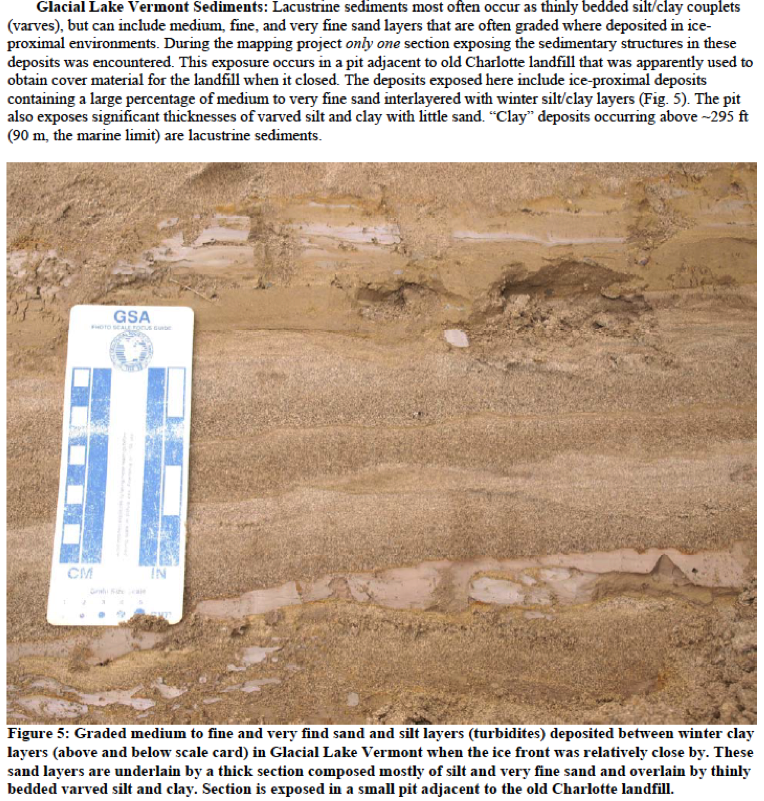

Plate 5 shows an interpretation of the favorability of surficial materials based on a classification of the stratigraphy of the surficial deposits in the bedrock and surficial wells. As shown on Plate 5, the high-yielding wells in surficial materials are generally buried in sand or gravel below thick clays. These wells are scattered throughout much of the town.

In my opinion, the information cited above by Springston and Wright is consistent with and lends support to a calving ice margin with oscillations, but as with the Connally report the evidence does not preclude a readvance.

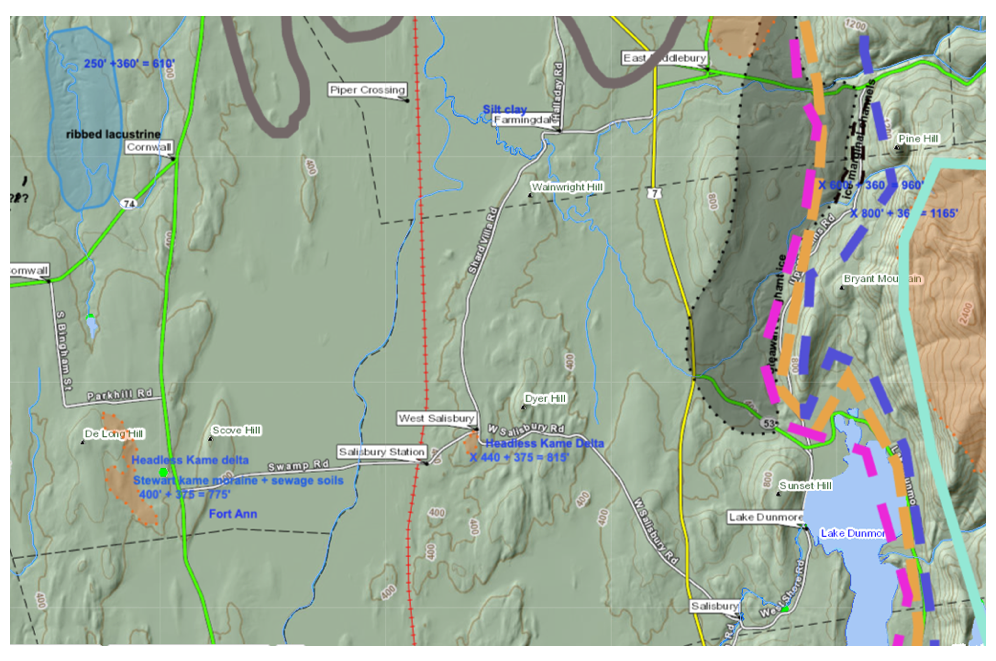

Van Hoesen(2016) 17Van Hoesen, J.G., 2016, Final Report Summarizing the Surficial Geology and Hydrogeology of Monkton, Vermont; Vermont Geological Survey Open File Report 2016-2, 36 p studied the Monkton area which is southeast of Charlotte and northeast of Middlebury, in the “Middlebury Bench” area. Lacustrine deposits are described(page 21) as “well-sorted, well-stratified silt-clay deposits commonly forming distinctive topography in the valley bottoms.” Van Hoesen’s “distinctive topography” is regarded as significant, as discussed further below in regard to “Ribbed Lacustrine” deposits, giving evidence in support of and indicative of calving ice margins. The author also notes that well logs indicate that sand and gravel deposits occur in some places below the lacustrine deposits. The meaning or significance of this observation, and the presence or absence of boulders in lacustrine deposits is not discussed, but is here believed to be consistent with a calving ice margin, such deposits being commonly reported in the literature related to meltwater basal tunnel drainage at such margins.

Finally, as discussed in Appendix 4, a number of reports have identified ice margin positions in the Champlain Basin in New York, as for example by Franzi and colleagues, some of which have been utilized below in the historical section of this report to illustrate possible regional correlations of ice margin positions. For example, the map below is taken from Van Hoesen et al’s “Ode to Chapman.” 18Van Hoesen, J.G., et al, 2016, A Cartographic Ode to Chapman: A revised regional depiction of Postglacial Landscape Evolution in the Champlain Valley; Geol Soc America Poster Presentation. This map shows multiple ice margin positions extending across the Champlain Basin between Vermont and New York. According to Franzi (2024, personal communication), who was one of the co-authors, he believes that Champlain lobe ice margins in New York, which extend eastward across the basin floor, as for example shown on this map, likely were calving, based on the substantial water depth of Lake Vermont, which supports flattened margins as depicted on the Ode map. But Franzi indicates that the positions of calving ice margins as they cross the Basin floor from New York into Vermont, including positions in Vermont, have not been documented and were drawn schematically, as flattened lobe margins so as to suggest calving. In my opinion flattened ice margins such as depicted on the Ode map reflect a paradigmic model in contrast to the evidence for a long, convex-shaped Champlain lobe as presented here.

The Ode to Chapman map below, represents typical, conventional thinking about ice margins, first that they are represented by simple lines on a map, and second that in the Champlain Basin the recession of the ice margin was from south to north with a flattened lobe associated with calving.

Again, this represents a paradigm that can be seen, for example in the thinking of Chapman, and in more recent reports in Vermont and in Quebec.19This is referred to here in a separate discussion as a “Paradigm Trap.” The evidence here indicates such margins were much more complex, as for example as hybrid margins with both active ice and stagnant ice components. Further, ice margins in Vermont were fronted by standing water, which had a very significant impact on ice margins, first by the development of narrow standing open water corridors or complex crevasse labyrinths of “Disaggregated Margins” along lateral margins as discussed elsewhere herein, which closely followed the physiography, and second, as well by calving which likewise shows and underscores importance of physiographic influences. The configuration of the ice margin represents a major Glacial Dynamic which played out in the recessional history of the Champlain lobe. The effectiveness of standing water along the ice margin is discussed here in regard to calving, but this Dynamic is likewise illustrated by the previous discussions of Scabby Terrain and Disconnections indicating en masse stagnation of ice masses along the Lake Winooski strandline, as discussed above, and by the development of Ice Tongue Grooves. This observation is very significant with regard to modern global warming concerns about the impact on ice sheets such as in Antarctica and Greenland. Whereas VCGI mapping only provides relative time differences and not absolute times or dates for the ice margin recession, the information shows a substantial increase in meltwater, with ponding in reverse gradient settings, suggestive of and consistent with a very rapid recession of the ice margin in the Champlain Basin, with instability, likely but uncertainly beyond a tipping point. The message here for global warming concerns is that penetration of water along ice margin, especially as ponded water bodies coalesce and become more regional, may trigger Glacial Dynamics having major impact on today’s ice sheets. The configuration of the terrain, or “Bath Tub” is important in that regard.

As a sidebar summary commentary related to the preceding literature review and its bearing and significance in regard to the VCGI mapping and associated historical interpretations given here, the following observations can be taken from the above as an advance preview of the deglacial history in the Champlain Basin:

- Whereas previous studies in Vermont have not specifically identified and delineated calving ice margins or set forth a deglacial history, they provide information which is suggestive of and consistent with a calving margin history as developed here and described below. Stewart and MacClintock’s mapping of bouldery versus non-bouldery silt-clay deposits provides information, as they state, that suggests the presence of calving of the Champlain lobe on the Basin floor. Their observation that in places these deposits resemble a till plain is significant. It is not clear from their report where this observation came from but may have reflected a contribution from Calkin in the Middlebury area and Connally further south in the Brandon, Ticonderoga, and Bridport area. Clearly, Calkin was struggling with the meaning of such deposits, but his observation that a substantial number of exposures in such deposits are varved is important, as is his conclusion that whereas stratigraphic variations within these deposits might suggest ice readvance or oscillations of a calving ice margin, his evidence favors the latter.

- In the Bridport area, also on the Basin floor but slightly further south than the Middlebury area, Connally recognized the occurrence of a bouldery silt-clay, which along with the stratigraphic and structural evidence at the West Bridport exposure led him to postulate a readvance of the ice sheet.

- Springston and Wright likewise recognized a bouldery silt-clay material in the Charlotte area, just north of Middlebury, leading to their suggestion of a climatically significant readvance related to a “Deformation or Readvance Till” as distinct from a lodgement till. Unfortunately, they did not depict the distribution of their Deformation Till locations on their map.

- As discussed below, the Hinesburg/Middlebury/Charlotte/Bridport area on the Basin floor was examined as part of the VCGI mapping reported here, including information from limited field mapping, leading to the following observations as related to the previous work just described in the above:

-

-

- A step-down sequence of ice margins at the T4-T6 levels and times leading to Coveville Lake Vermont is mapped on VCGI along the foothills margin of the Basin floor in early T6 time. The evidence indicates that Coveville Lake Vermont then existed in a long narrow standing water corridor, extending northward to the Hinesburg area in early T6 time, with an ice dam across the Winooski Basin resulting in the impoundment of major water bodies, specifically Lakes Winooski and Mansfield in the uplands.

- Three calving events are identified. The first in early T6 time is inferred as a possible calving event related to the lowest “Deep Lake” portion of the Basin floor. If present, this event would be marked by features in New York State and not likely in Vermont. The second calving event occurred in late T6 time when Lake Vermont lowered from the Coveville to the Fort Ann level. This event is marked by many features at the Fort Ann level, including features as just described from the previous work of others, and as well features mapped here on VCGI as discussed below. The third event occurred in T8 time when Fort Ann lowered to the Champlain Sea.

- The second and third calving events, triggered at times of major lowerings of regional proglacial water bodies, were associated with ice streams in physiographic re-entrants within the “Middlebury Bench,” including the LaPlatte Basin where Wright and Spingston’s mapped features in the Charlotte area, the Little Otter Creek/New Haven River basin where Calkin mapped the Middlebury area, the Monkton area mapped by Van Hoesen’s, and the Otter Creek basin and Main Trough of the Basin, including Connally’s mapping, and as well important features mapped on the State map. Also, Springston and DeSimone’s mapping of features in the Sucker Brook basin is in a small but not insignificant re-entrant at the mouth of the Winooski Basin.

- The beginning of the second phase of calving in late T6 time associated with lowering from Coveville to Fort Ann is marked by “Ribbed Lacustrine,” “Thickened Bouldery Silt and Clay,” and “Headless Delta” deposits on the floors of the re-entrants as delineated on the State Surficial Geologic map, and other features as discussed below, extending downgradient from the heads of these Basins. This mapping is in remarkable agreement with, and documents and supports the calving history described here, which is a testament to the careful thinking and observations of Stewart and MacClintock and their field team.

- The progressive recession of the calving margin for ice streams in each of the re-entrants during this second phase is also marked by other calving ice margin features as discussed below. Features identified by VCGI mapping and as well by previous works, by Stewart and MacClintock, by Wright in the LaPlatte Basin in the vicinity of old Charlotte landfill, by Springston and DeSimone at Sucker Brook, by Van Hoesen in the Monkton area, by Calkin in the Little Otter Creek/New Haven River Basin, by Connally in the Otter Creek and “Trough” Basins, and by Cannon and Wagner in the Missisquoi Basin, all correspond with the calving ice margin recession near the end of the second phase of calving at the beginning of the third phase of calving, associated with Fort Ann to Champlain Sea water level lowering.

- Ice margin features indicate the Champlain ice lobe was long and convex in plan view, with calving along the ice stream fronts in each of the re-entrants in late T6 and T7 times, and with a narrow standing water corridor extending progressively northward along the eastern margin, eventually into Quebec, while the ice sheet still projected far to the south in the Basin. The third phase of calving was triggered by the lowering of water levels from Fort Ann to Champlain Sea, associated with invasion of the Champlain Sea in T8 time along this corridor.

- Evidence identified by Cannon and Wagner’s mapping in the 1970s in the Missisquoi Basin indicates a readvance of the ice sheet took place in T8 time. The extent of the ice margin recession prior to this readvance and therefore of the readvance itself, and the climatic significance, if any, are unknown. Nor is it clear if this readvance re-established a freshwater water body above the Sea, though Wagner(19721) offered speculation in this regard. As discussed below, the ice sheet in the Champlain Basin at this time remained as a long, convex ice lobe, with recession taking place as much or more by shrinking of the eastern margin in a western direction as opposed to northward recession. 20 In the final, concluding section of this report, helpful comments by Dave Franzi led to my questioning the nature of this long, convex ice mass. This allows for a correlation of features as described by Wright and Springston and by Connally with the recession and readvance of the ice margin in the Missisquoi Basin, with the recession consistent with an ice margin oscillation and not necessarily requiring a major readvance as proposed by Connally and Wight et al.

- The T8 margin, including the readvance evidence in the Missisquoi Basin is correlated with the features associated with the third phase of calving in the LaPlatte, Little Otter Creek/New Haven River, and Otter Creek and Trough ice streams, again indicating a long convex ice lobe extending southward to the Bridport area, with a long narrow standing water corridor along the eastern margin of the lobe. The correlation of features in the Missisquoi Basin with features as far south as Bridport, was initially regarded as problematical in as much as Wagner’s mapping of many deltaic deposits at the Champlain Basin showed no evidence of readvance in these deposits. This thinking is an example of the danger of paradigm trap thinking in as much it reflects the traditional thinking of the progressive northward recession of flattened ice margins. However, a long convex lobe with a standing water corridor along the eastern margin fits with recession and resolves this conundrum. Such a lobe configuration suggests both south to north and east to west recessional components, whereby the readvance identified in the Missisquoi Basin can be correlated with features to the south without requiring a large north to south readvance over a substantial distance. The nature of the readvance as a significant climatic event, as suggested by Connally and Wright versus a calving ice margin oscillatory event as suggested by Calkin, is unknown but the evidence does not require a more major climatic event.

-

An additional point needs to be made in the context of this literature review, as a kind of sidebar to this sidebar:

In general, the prevailing, traditional view of deglacial history in Vermont is that the recession of the ice sheet and associated proglacial water body history took place as a relatively well-defined, sharp-edged, staccato-like progression of receding ice margin positions through time., much like simple lines on maps. This was not the case. Ice margins were broad, hybrid margins, with complex spatial and temporal relationships during recession. Likewise, the proglacial water body history similarly has been classically viewed as a relatively simple step-down progression of lowering water levels. This understanding of the ice margin and water levels represents a mental model or paradigm. Again as discussed elsewhere in this report, paradigms are fundamental and necessary elements of human thinking but they tend to imbed thoughts and concepts which may or may not be correct. The danger is that our thinking and understanding proceeds without being recognized as such.

Franzi(2025, personal communication) believes and is now in the process of reporting, that the prevailing model or paradigm previously established by Chapman for the Champlain Basin proglacial water body history is incorrect and needs to be revised. His findings indicate that the stair-step recession of water levels as outlined by Chapman is oversimplified, that the levels of these water bodies were temporally and spatially more variable. As noted above, he uses the term “diachronous” to signify his view that the ages of individual strandlines were not everywhere the same.21Wikipedia states: “In geology, a diachronism(Greek dia, “through” + chronos, “time” + -ism), or diachronous deposit, is a sedimentary rock formation in which the material, although of a similar nature, varies in age with the place where it was deposited.” In a sense, this has long been recognized in geologic thinking as embodied in the “facies” concept. This concept fundamentally recognizes that the strandlines formed along the receding Champlain lobe ice margins, which receded through time, must therefore be different ages at different places along the same strandline.

It is here believed that the same thinking applies as well to ice margins. In this report, ice margins are distinguished based on elevation, as though they represent time lines, which has been a helpful way of raveling and constructing deglacial history. However, it needs to be recognized that this is a paradigm which tends to simplify our understanding in order to make it comprehensible, but in the process distorts the resultant historical story.

For example, in this report deglacial history is explored with reference to a relatively straightforward sequence of progressively lower and younger ice sheet levels in a “Bath Tub Model.” These levels thus provide a temporal chronology which define ice margin positions, leading to the usage of the terms and concepts of levels and times interchangeably. However, such levels and their implicit ice margin positions, like strandlines as now regarded by Franzi, were likewise diachronous, because in fact they are not true “timelines”(meaning markers along ice margins which everywhere along the time line are the same age). This fundamentally is because, in part, the ice margins and timelines identified here are imprecise and at best approximations of times,

Further, the evidence indicates that ice margins involved both active and stagnant portions as hybrid margins, and that these receded in tandem, but that owing to their insulating sediment cover stagnant ice margins persisted longer than their active ice margin counterparts. This is referred to in the Memphremagog Basin as a distinctive Style described as “Everything, Everywhere, All at Once and Continuing.” Thus, for example, in the discussion here about calving history, it was found necessary to make a distinction between early T6 versus late T6 levels and times. This distinction in a sense is an acknowledgement that the selection and usage of levels for the deglacial history is not correct in regard to details, and that the Bath Tub Model validity is limited and at best a guide. And while that may be true, the fact is that such chronologies are intrinsically incapable of describing a natural history in which events fundamentally involved overlapping and gradational temporal and spatial elements.

The diachronous nature of both ice margins and strandlines becomes even more complex when one recognizes that Champlain Sea features likely progressed from older to younger in a south to north direction along the ice sheet front margin, but as well north to south in the standing water corridor marking the progressive invasion of the Champlain Sea into the Basin.

In the end, rather than attempting to devise the “perfect” chronology it is preferable to recognize that our understanding of deglacial history is at best a gross artifice which likewise no doubt will need to be revised and refined in the future, as our understanding improves, yet again and again. It seems that the dilemma ultimately relates to the limits of the human mind. Humans are good at thinking spatially in two dimensions, less so three dimensionally, but added temporal complexity challenges the thought process to and perhaps beyond the mental capacity of most mortals. The same applies to reporting, which after all is merely a written communication form of thinking in a two dimensional format. Simple two dimensional concepts can be comprehensibly reported relatively easily and briefly. Adding a third dimension is mechanically more challenging but can be done by clever graphics, still keeping the story relatively brief. Additional temporal complexity, however, strains not only the narrative and accompanying graphical mechanics, but unavoidably adds substantially to the length of reports. For the reader, who is the receiver of the new information presented here, such lengthy discussion which tends to drone-on-and-on in a seemingly unending and repetitive narrative, is a wonderful antidote to sleep problems. We humans have a low threshold for long, convoluted, repetitive narrative, however, essential this may be. It might be true, as has been suggested, that our present day digital age information world places an even greater premium on brevity. All of which is to say here to the readers of this report: “If this applies to you, don’t bother reading on!” As difficult as this may be for you to read and plow through, it is nothing as compared to having to write and then edit such dronings.)”

c. Calving Ice Margin Literature

As is well known, concern about global warming has spurred considerable present-day interest in ice shelves. For example, in 2024 a recently developed research submarine successfully explored conditions beneath the Antarctic’s Dotson Ice Shelf, penetrating about 17 kilometers beneath the ice shelf, showing a variety of never before seen ice margin features and conditions. 22https://en.as.com/latest_news/advanced-submarine-makes-disturbing-discovery-in-unchartered-waters-then-suddenly-vanishes-n/ https://jasondeegan.com/the-ran-submarine-lost-17km-deep-in-antarctic-ice-reveals-the-hidden-side-of-the-south-pole/ These included evidence of accelerated melting at the ice/land/water interface, including subglacial tunnels and widened vertical fractures(crevasses) in the bottom of the ice shelf, and a wide array of sedimentary deposits formed by flowing water at the ice/ponded water interface, as for example “fluvial” dune-like features. Unfortunately, contact with the sub was lost and the mission ended prematurely. Obviously, the sub-glacial calving environment is complex and as yet little understood. This environment is so difficult to study and understand that present day glaciology literature tends to utilize mathematical modeling as a way of better understanding the mechanics of calving ice shelves. But modeling is limited by our imperfect and incomplete understanding, which is dangerous territory for modeling. In contrast, studies of past glaciation, such as in this case for Vermont, allow the examination of ice margin features across a much broader area, and at a fraction of the cost. Of course, both approaches together obviously provide the best information about calving margins.

As just stated, calving ice margins are extraordinarily complex and still not well understood. A complete and detailed review of recent scientific literature on calving, which deals with both the disequilibrium physical dynamics of ice and water along ice sheet margins and as well different types of features found along such margins faced with such dynamics, is beyond the scope here.

In general, calving ice margins obviously and by definition form in close association with proglacial standing water bodies and tend to be oscillatory in nature, with temporal recessions and advances of the grounding line. As a consequence, features formed at calving ice margins show this close glacial and proglacial environmental setting relationship. Many reports indicate an interbedded mix of till, standing water deposits, and fluvial materials originating at meltwater outflows from the ice sheet, which is made more complex by oscillations of the margin, with a variety of geomorphic forms with diverse internal stratigraphic and structural complexities.

Some examples of the literature give a sense of calving ice margin features and evidence:

- As noted above, one of the earliest features reported in the older and now classical literature as being indicative of calving ice margins is ice rafted boulders in lacustrine sediments, such as described above for the “bouldery lacustrine(and marine)” deposits. Such deposits have long and routinely been interpreted as iceberg drop deposits. Thus, extensive and substantial bouldery lacustrine deposits likely indicate the presence of a calving ice margins. Other related features include grooves and mounds caused by iceberg ploughing along shallowing water margins.

- De Geer moraines, which are multiple moraine-like ridges, have similarly been long and classically recognized in conjunction with late Pleistocene coastal ice margins. Different theories have been advanced for their formation, as for example plowing of basin floor sediment by the ice sheet at the grounding line, or upward injection of sediment into basal crevasses.

- Powell 23Powell, R.D., 1990, Glacimarine processes at grounding-line fans and their growth to ice contact deltas; Geol.Soc. London, Special Publications; pp. 53 – 69. identified alluvial fans and deltas as grounding line deposits formed by meltwater outflows at the base of the ice sheet at the mouths of calving ice margin tunnels. This is reminiscent of the descriptions given above from Vermont literature of gravel deposits beneath lacustrine deposits, and may as well be related to “Headless Delta” deposits as described below.