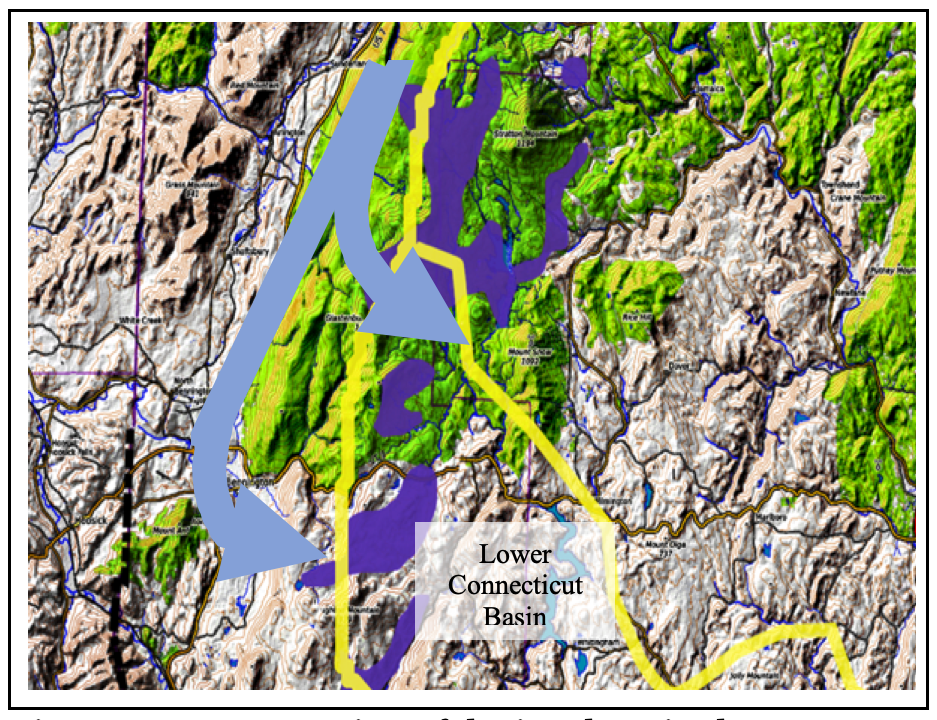

The map below depicts the T1 time and level ice margin marked by Scabby Terrain(dark purple) at an adjusted elevation of about 3120 feet along the western perimeter of the Lower Connecticut(Deerfield) Basin, the boundary of which is shown by the yellow lines. This represents the earliest and highest ice margin position of the ice sheet in the Lobate Phase mapped in Vermont; older and higher ice margin features were identified, specifically Ice Marginal Channels in the Nunatak Phase, but these generally were not used to delineate ice margins.

The blue arrows represent a schematic depiction of Champlain lobe flow lines into the Lower Connecticut Basin from the Champlain lobe in the Vermont Valley, almost like a “Bath Tub” overflow, prior to the Disconnection that resulted in en masse stagnation of the ice in that basin as marked by the Scabby Terrain. Prior to T1 time the level of the ice sheet in the Champlain Basin was high enough to sustain active ice flow across the divides at cols into the Lower Connecticut Basin, but in T1 time the lowered level resulted in a Disconnection, causing en mass stagnation of the ice sheet in the Lower Connecticut Basin. Locale LC1 in Appendix 2 discusses this in detail. The elevation of the ice sheet at T1 time in the Champlain Basin was slightly above the Scabby Terrain at the 3120 foot(951 m) level. The Scabby Terrain marks the margin of the en masse stagnated ice, not the margin of the ice sheet in the Lobate Phase.

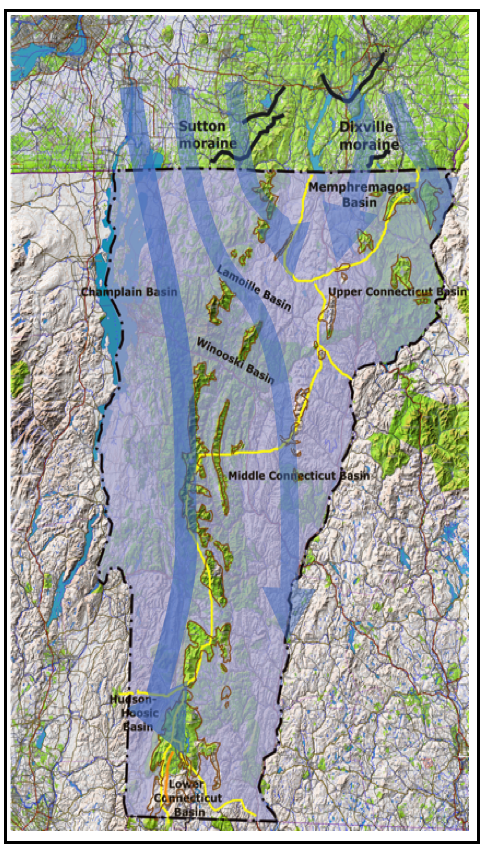

The Statewide map here shows the T1 ice margin by an orange-colored line along the western margin of the Lower Connecticut Basin, with areas of active ice cover at that time by blue shading. The T1 ice margin pre-dated the Dixville moraine. The margin is not shown extending westward into New York and eastward into New Hampshire owing to insufficient information about correlations in these areas. Obviously, en masse stagnation in the Deerfield Basin has implications for the area of the basin to the south in Massachusetts, which has not been examined.

The T1 elevation was below the highest peaks along the crest of the Green Mountains which appear as nunataks on the above map. The T1 level in northern Vermont was not mapped, but multiple peaks above the ice sheet in T1 time are shown schematically on the above map to symbolize such Nunataks. In general, the T1 level was above the highest Ice Marginal Channels in northern Vermont. The absence of markings in this area likely is attributable to thin soils with shallow bedrock and perhaps as well by limited meltwater at this time.

Flow lines are shown on this map suggesting ice flow pathways. These are drawn schematically to give a general sense, and more specifically to show a pathway in the southern Vermont Valley near Bennington, with easterly ice flow across the divide into the Lower Connecticut Basin where the Disconnection in T1 time resulted in the development of Scabby Terrain in that basin. Obviously the direction of ice flow presumably may as well be indicated by striations, till fabric, and other indicators, which are not given by VCGI but are reported in the literature. I am aware that many studies have indicted a general ice flow from the northwest to southeast, and that Stewart and MacClintock have identified flow directions which they interpret as multiple ice advances. It is likely that the ice flow generally was regionally more NW to SE than shown on the above map, but as discussed above Stewart and MacClintock’s directional evidence may be interpreted so as to support ice flow in conformance with the physiography of the Vermont Valley. For example, De Simone and LaFleur(1985, ibid, p. 87), who mapped neighboring areas of the Taconics in New York, including portions of southwestern Vermont, state: “Taconic Highland deglaciation was characterized by a thinning ice cover that exposed till-veneered hills and also by active ice tongues in those valleys oriented parallel to the direction of ice flow.” They present striation maps showing ice movement for the Champlain lobe in the area of New York immediately west of the Rutland-Bennington area in a NNE to SSW direction. Additionally, their ice margin position map clearly reflects a strong physiographic control on ice margins.

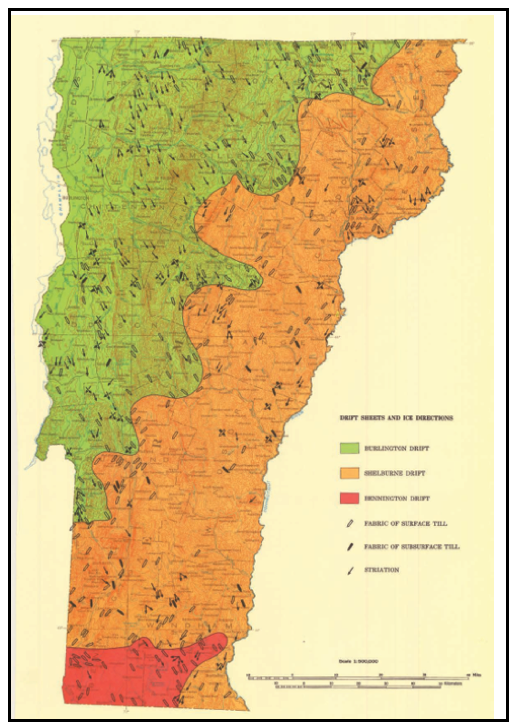

Interestingly, as just mentioned, Stewart and MacClintock determined Vermont glacial history based on till fabric and striations, as depicted on an inset on the State Surficial Geology map, as again shown below.

Three drift sheets were identified, specifically in order from older to younger, the Bennington(red) with NW-SE fabric, the Shelburne(russet) with NE/SW fabric, and Burlington drift sheet(green) with NW/SE fabric. Examination of this map raises the intriguing possibility that the Shelburne drift may relate to the en masse stagnation in the Connecticut Basin, which took place in three phases, T1 time being the first phase. In other words, by this explanation Stewart and MacClintock’s three drift sheets might all be related to a single ice advance with the fabric and striation differences associated with physiographic influences. This explanation illustrates the significance of paradigm-ic thinking as discussed above in regard to paradigm “traps.” As can be seen, the striation evidence used by S & M to identify their Bennington till in fact suggests and is compatible with eastern ice movement from the Vermont Valley portion of the Champlain Basin into the Lower Connecticut Basin.

Apart from the issue of pathway and ice movement direction, the primary significance of the T1 finding presented here is that the ice sheet in the Lower Connecticut Basin (or Deerfield Basin) was nourished by “overflow” of ice from the Vermont Valley, eastward via cols into that Basin which at T1 time became Disconnected, resulting in en masse stagnation. Again, the absence of Ice Marginal Channels in the Lower Connecticut Basin is consistent with this hypothesis, as is the predominance of till and shallow bedrock, with only scattered small local stagnant ice deposits on basin floors. It is suspected that the ice sheet more generally is marked by a recessional history in the Connecticut Basin that indicates local but relatively insubstantial ice margin features below the T1 level. This reflects the fact that ice flow serving to supply sediment to such features was limited.